The new United States-Mexico-Canada trade deal (USMCA), which President Donald Trump announced Monday, is a lot like NAFTA but with a few upgrades.

For one, it increases the amount of dairy products that US farmers can export to Canada without tariffs, while allowing more Canadian peanut products into the United States untaxed. It also requires US automakers to use more car parts made in the United States to avoid tariffs.

But the most striking difference from NAFTA involves protections for workers in all three countries. Mexico has agreed to pass laws giving workers the right to real union representation, to extend labor protections to migrant workers (who are often from Central America), and to protect women from discrimination.

American auto companies that assemble their cars in Mexico would also have to use more US-made car parts to avoid tariffs, which would help US factory workers. And about 40 percent of those cars would have to be made by workers earning at least $16 an hour — three times more than Mexico’s minimum wage for an entire work day.

And unlike NAFTA, the new deal allows each country to sanction each other for labor violations that impact trade. It’s a complex, multi-step process modeled after similar protections in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), a trade deal that Trump pulled the United States out of after taking office.

These are much-needed reforms, and they address a lot of concerns that US labor unions have long had about NAFTA. It’s one thing to make trading partners adopt strict labor laws, but making sure they enforce those laws has proven much, much harder.

Under the USMCA, doing so will still be a challenge — but unlike NAFTA, the new deal at least has a defined process to legally enforce labor rules.

NAFTA was bad for low-skilled workers in Mexico and the United States

Free trade between the United States, Canada, and Mexico has had a small, but positive, impact on all three economies. Free-trade advocates love to point out all the jobs that NAFTA created but often downplay all the jobs it wiped out.

When NAFTA was enacted in 1994, labor unions worried at the time that allowing goods to cross the border untaxed would give US manufacturers too much incentive to move factories and jobs to Mexico, where wages were super low and environmental standards more relaxed.

Proponents of NAFTA pushed back against that idea, saying that boosting trade would raise wages for low-skilled Mexican workers, pulling millions out of poverty and making it less attractive for companies to move factories to Mexico.

That definitely didn’t happen. Competition from US farms was largely responsible for putting more than 1 million farmworkers in Mexico out of work, and the unemployment rate in Mexico is higher today than it was back then.

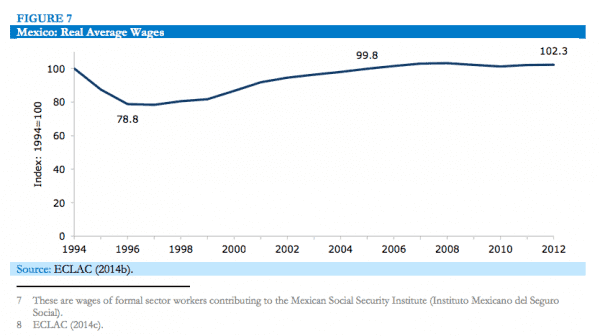

On top of that, wages for workers in Mexico have hardly budged. Just look at this chart from the Center for Economic and Policy Research:

In the United States, NAFTA didn’t lower overall US wages, as some feared, but it was linked to lower wages in some manufacturing jobs. The trade deal was also directly responsible for the loss of more than 840,000 US factory jobs, most of which were moved to Mexico. Just last year, Ford announced it was closing one of its auto factories and opening another one in Mexico.

US companies are still doing this because factory workers in Mexico are still making poverty wages. And one reason workers in Mexico are still living in poverty is because NAFTA’s labor protections have not been enforced.

NAFTA was also supposed to protect workers, but it didn’t

When NAFTA was signed, it included labor protections for workers in all three countries: the US, Mexico, and Canada. Basically, each country agreed to enforce its own labor laws and follow standards set by the UN’s International Labor Organization.

But labor complaints filed through the NAFTA labor dispute process have led nowhere.

About two-dozen complaints of workers’ rights violations were filed against all three countries in NAFTA’s first decade — the vast majority in Mexico, according to Human Rights Watch. Companies accused of violating local labor laws include General Electric, Honeywell, Sony, General Motors, McDonald’s, Sprint, and the Washington state apple industry.

In Mexico, those complaints included allegations of retaliation against workers who tried to unionize, denial of collective bargaining rights, forced pregnancy testing, mistreatment of migrant workers, and life-threatening health and safety conditions. None have led to any type of sanctions, which workers’ rights groups say is because there are no rules about how to resolve these disputes and government mediators have chosen to take a hands-off approach.

“Our research shows that agreements on labor will never work without the active support of the countries involved. In the case of NAFTA, these three countries have actually worked to minimize the impact of the labor provisions,” the HRW report stated.

One of the biggest complaints against Mexico right now is that labor unions are largely controlled by employers, and workers are not even part of contract negotiations. So it’s no wonder why Mexican factory workers are earning so little. The average hourly wage for factory workers in Mexico is just over $2 an hour, and the country’s minimum wage is roughly $4.15 for a full day’s work. These low wages attract US companies to operate in Mexico.

The new labor rules in Trump’s pact with Mexico are supposed to remove the incentive to keep Mexican workers living in poverty. Under the new deal, the United States can use the same dispute system to resolve labor complaints that NAFTA previously allowed only for commercial trade violations (such as exceeding trade quotas).

Mexico must pass new labor laws for the trade deal to go into effect

As part of USMCA, Mexico has promised to pass laws that will guarantee workers the right to form unions and negotiate their own labor contracts. If Mexican workers could do this without fear of losing their jobs, they would certainly negotiate better wages and working conditions.

Right now, workers in Mexico have the right to unionize, but they are often left out of the negotiating process. US manufacturers — and most other companies — end up dictating the terms of the contract with labor unions to their own benefit. Workers have also reported retaliation from employers when they try to create a labor union.

The new pact would also require Mexico to pass a law extending labor protections to migrant workers, many of whom come from Central America and are vulnerable to exploitation.

The “new NAFTA” would allow the United States, for example, to file labor complaints through the regular dispute resolution system, but only if it involves labor violations that are harming US trade. They can bring the complaint before a commission of government labor ministers from each country, but only after exhausting all efforts to mediate the issue and resolve it separately.

The commission is then supposed to weigh the evidence and facts, to determine if Mexico (hypothetically) is not enforcing the deal’s labor rules, and whether that harmed US companies. If so, the United States could slap tariffs on certain products entering the United States from Mexico until US companies can recoup the money lost.

It seems like a long, painful process that could take months to complete. But it’s better than the nonexistent process under NAFTA. And it would require each country to take an aggressive, hands-on enforcement approach.

The most challenging part will be enforcing a specific provision in USMCA that mandates that 40 to 45 percent of a car’s parts must be made by workers who earn at least $16 an hour to avoid tariffs. That means that many Mexican factories that make parts for US car manufacturers would have to pay eight times what they currently pay the average factory worker. Or auto manufacturers would simply need to buy more car parts made in the United States, where wages for factory workers are much higher.

The trade deal does not mention how the US government would even know what companies across the border are paying their workers. It’s not clear how the Mexican government would know either. But Mexico’s president-elect, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, is a populist politician whose campaign focused on improving working conditions for Mexico’s poor.

Whether USMCA’s labor protections are effective depends in large part on whether he keeps his promise to voters.

Sourse: vox.com