Anthony Joshua and Francis Ngannou meet in a heavyweight clash live on Sky Sports Box Office on Friday March 8; scroll down for booking information – how and when to book via remote or online

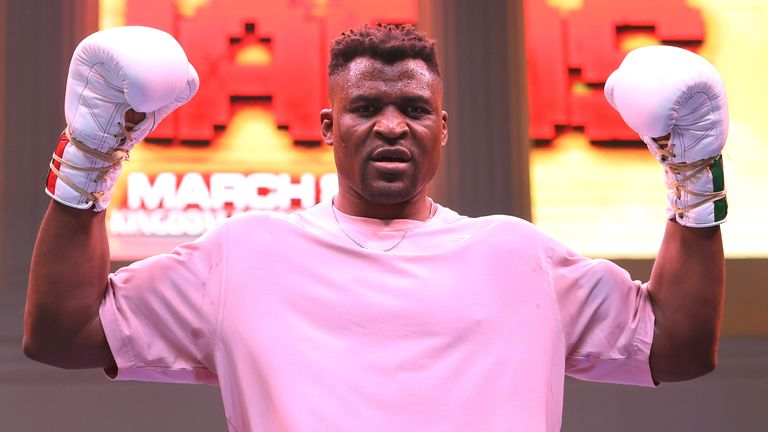

Francis Ngannou puts on a performance for Anthony Joshua’s trainer Ben Davison at the open workouts for their fight on Friday

Francis Ngannou claimed Anthony Joshua has been looking nervous ahead of their heavyweight bout in Saudi Arabia on Friday, live on Sky Sports Box Office.

Joshua is the clear favourite to win in Riyadh but Ngannou, the 37-year-old former UFC star preparing for only his second professional boxing contest, went the full 10 rounds with Tyson Fury last year and floored the WBC champion in a match-up he controversially lost on points.

That will give Joshua, 34, plenty to think about as he eyes a potential world title fight against Filip Hrgovic, or a bout against the winner of May’s showdown between Fury and Oleksandr Usyk.

“We were doing the promo and he was very chilled, very relaxed,” Ngannou told reporters at a workout on Tuesday.

- Joshua vs Ngannou: All you need to know

- Joshua vs Ngannou: How to book Friday’s fight

- Book Joshua vs Ngannou online now

- The remarkable rise of Francis Ngannou

- Get news and analysis from Sky Sports on WhatsApp

“I asked him if he was OK, because he looked a little nervous or something. I asked him if he was OK, because I was OK. I had no problems. I was just talking around, laughing.

“I think we are both professional enough to know what we have to do to get to where we want to go.”

Image: Ngannou has claimed Joshua ‘looks nervous’ ahead of their fight, with AJ saying ‘talk is cheap’

Promoter Eddie Hearn looks ahead to Joshua’s fight against Ngannou and a potential future fight with Tyson Fury

Joshua opted against hitting the pads during his own workout, instead shadow boxing alongside a number of local young boxers invited to attend.

“It’s a great chance for me to let other people use the platform that I’ve created to express themselves and their talent,” Joshua said.

Frank Warren weighs up the ‘risk and reward’ for Joshua in his fight against Ngannou this Friday on Sky Sports Box Office

“I know how much the people of Saudi are embracing boxing and health in general. I gave them a chance to get on TV and hopefully their parents will see and it will boost their morale.

“I’m here to fight, I wasn’t acknowledging [the fans] with all due respect, I’m here to fight. This is my life. Talk is cheap.”

Joshua’s promoter Hearn believes Joshua’s pressure will make Ngannou gas out in their bout on Friday

Anthony Joshua’s heavyweight showdown with Francis Ngannou takes place on Friday March 8, live on Sky Sports Box Office with the main event expected around 11pm. Book now!

When is the fight and how can I book?

The event will start at 4pm, Friday March 8 on Sky Sports Box Office (Sky channel 491) and Sky Sports Box Office HD (Sky channel 492). The event is priced at £19.95 for Sky customers in the UK, €24.95 for Sky customers in the Republic of Ireland up until midnight on Thursday March 7.

Thereafter £19.95/€24.95 across all “self-service” bookings (remote control/online) or £24.95 / €29.95 if booked via the phone (either IVR or agent) but note an additional £2 booking fee if via an agent will apply.

The event price will revert back to £19.95 / €24.95 (ROI) from midnight Friday March 8. Two repeat showings (full duration) will be shown at 6am and 4pm on Saturday March 9.

Get Sky Sports on WhatsApp

You can now receive messages and alerts for the latest breaking sports news, analysis, in-depth features and videos from our dedicated WhatsApp channel.

Find out more here…

Sourse: skysports.com