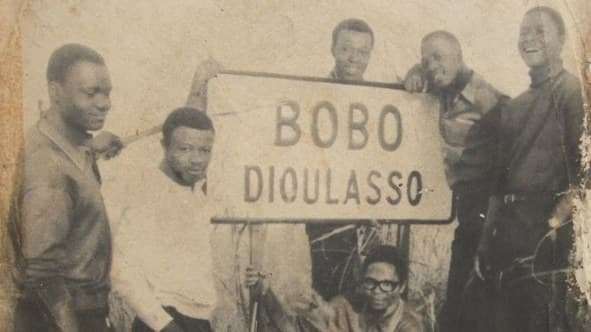

This story begins with the betrayal of a husband and ends with the betrayal of an entire country. Its setting is West Africa, the city of Bobo-Dioulasso. Bobo is in the south of Upper Volta, the country now known as Burkina Faso. The city has wide avenues where people shelter from the heat under the spreading branches of giant shea trees, and many of its denizens fill the long tropical nights in its bars and cafés. In 1959, a year before Upper Volta’s independence, from France, Brahima Traoré, the son of two musicians, hears that a Frenchman, Jean-Pierre Bordas, has arrived in town with his wife and wants to form a band. “He wanted a guitar player,” Traoré told me.

On a Sunday night, Traoré goes to see if he can play in Bordas’s band, and a group of other hopefuls is crowded around the Frenchman. “He is showing them how to make shapes with their fingers on the guitar. He calls someone over, but that man can’t do it.” Traoré shouts out, “Me, monsieur!” Bordas motions to him to approach, and Traoré makes shape after shape with his fingers. “Me, I could do them all.”

The next morning, he begins his apprenticeship with Bordas. “By the end of the day, I could accompany him by myself,” Traoré told me. “I’d never played before. And that’s how it started.” Soon they have recruited other musicians, and founded a band. The word “jazz” is popular in Africa at the time, and even though they’re not playing jazz, the band is named Tropic Jazz. “It’s related to some kind of modernity,” Florent Mazzoleni, a French music producer and writer who has studied the era, has said. “It related somehow to America, black America. And jazz was a means to distinguish oneself from the past and basically to move ahead and to live with your time.”

As independence sweeps through Upper Volta in 1960, Bobo has the advantage of a railroad that connects the city to the port of Abidjan, in Côte d’Ivoire. The city becomes prosperous, more alive. Tropic Jazz is there to fill the demand for modern music with their version of Yé-Yé, a popular French genre at the time.

The years of Tropic Jazz’s success, however, would be limited. “It was all because of a Congolese musician, a saxophonist, who arrived, and played the sax with our band. He had lived in the West, he wanted an adventure, and Bordas’s wife loved him,” Traoré said. It was 1964. The two eloped. “We don’t know where they went, but Bordas sold his instruments, and chased them on the train to Abidjan.”

At this point, Traoré’s friend Idrissa Koné enters the story. Koné was a former soldier in the French Army and had started an orchestra in Bobo nine years beforehand. He used money that he had saved up from his military service—seven hundred and fifty francs (about six hundred and ten dollars in today’s money)—to buy Bordas’s instruments. “He sold his material, and, when I acquired that material, I rebaptized the group,” Koné told me. “Instead of Tropic Jazz, I called it Volta Jazz.”

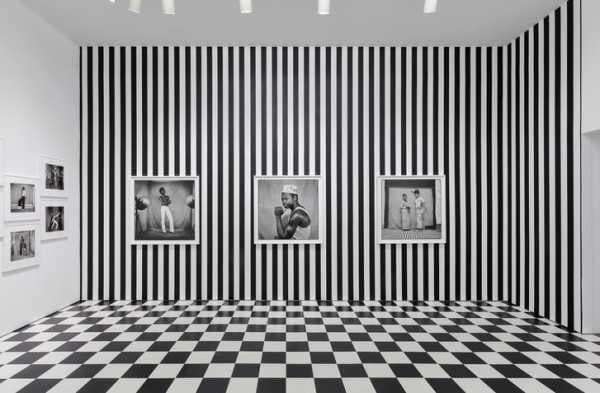

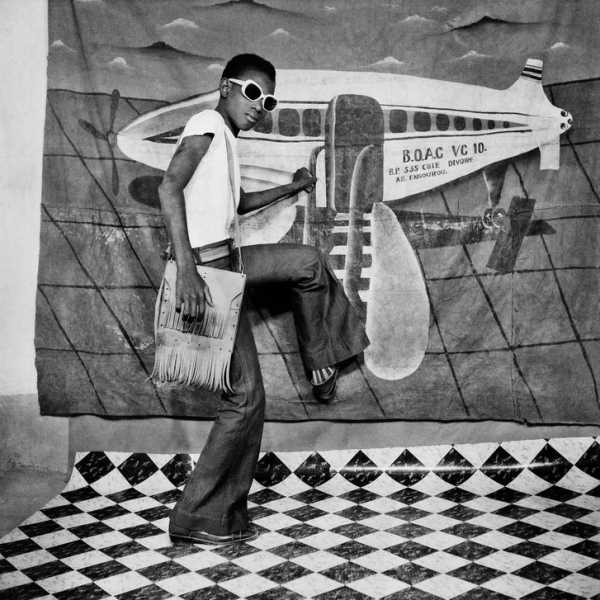

I became interested in Volta Jazz and post-independence Bobo-Dioulasso earlier this year, after seeing the photographer Sanlé Sory’s work exhibited in a show at the Yossi Milo gallery, in Chelsea. Milo had arranged Sory’s photographs of the Bobolais in a room that reproduced the setup of the studio where many of the images were shot. His photographs have a similar look to work by Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta, in neighboring Mali. Sory’s male subjects mimic stars like James Brown and Eddy Mitchell. The women cock their hips, arms akimbo, and glare into the camera. They pose with totems of modernity—sunglasses and cameras and vinyl records and motorbikes—and against painted backdrops of modernity—a large town and an airplane. (Sory would later tell me these were painted by a Ghanaian.) These people are metropolitan, worldly, and cool, and they vibrate with excitement for a new future.

An exhibition of Sanlé Sory’s photography at the Yossi Milo gallery, in Chelsea.

Photograph Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery

After a car ride of seemingly endless speed bumps from Ouagadougou, I am sitting in a café in central Bobo waiting for Sory. When he arrives on his scooter, he’s wearing a gray safari suit and a colorful kufi hat. The shadows of two tribal scars run across his cheeks. It is in great part thanks to the efforts of Florent Mazzoleni that the music of Volta Jazz and Sory’s photographs have been recently shown in France and the United States. The Art Institute of Chicago and Steidl have published a book about Sory’s studio that includes interviews between Mazzoleni and the photographer. Although the Voice of America recently ran an interview with two musicians from the Volta Jazz era accusing Mazzoleni of cultural banditry, Koné, Traoré, and Sory all told me that they were only thankful for Mazzoleni’s work in hunting down old recordings and images. Volta Jazz’s circa twenty singles and a full-length album were pressed in Abidjan, and the vinyl disks on which they recorded their music are exceedingly hard to find, even for the band members themselves. “Our new success is thanks to him,” Koné told me. A box set of Bobolais music produced by Mazzoleni, including many tracks by Volta Jazz, was nominated for two Grammys for 2018.

Sory tells me about how he moved to Bobo from the countryside in the nineteen-fifties. At the time, the colonial government required I.D. photographs, so a handful of studios had sprung up to meet the need. These images were basic, black-and-white, head-on, and fairly small. After a brief apprenticeship, he founded his own studio, Volta Photo, and began taking the larger posed photographs that he is known for today. He explained the developing process in depth and how, because he didn’t have the lighting equipment, he would use matches to enlarge pictures.

A fairly unique element of Sory’s practice were the bals poussières, or “dust balls,” that he used to throw in the countryside outside Bobo in the nineteen-sixties and seventies. Like the organizers of raves in the British and U.S. countrysides twenty years later, Sory put together a sound system and travelled to deserted spots out of town. He would often time the parties to a harvest, when farmers had money to spend. They would drink and dance into the early morning to a mixtape soundtrack of Bob Marley, Ghanaian and West African music writ large, and, of course, Volta Jazz. “They jumped like fish,” Sory told me, laughing. To turn a profit on the events, Sory would be on the prowl with his camera, selling photographs of the revellers to whomever could afford them.

Koné is a cousin of Sory’s, and so, when Volta Jazz needed pictures for album covers, the band turned to him. One of the group’s record sleeves is a cover of Volta Jazz in period tuxedos, the band in red and Koné as band owner and producer in black. “I took that,” Sory chuckles. He thinks of himself primarily as a black-and-white photographer, but the band wanted color. “I had to send away to get it developed!”

Sory takes me to see Koné later that afternoon. “When we became popular, I was really worried about spoiling it all,” Koné tells me. “When you get into the public view, you are known.” We sit in the green-painted courtyard of his home in Bobo, which also doubles as the headquarters for the Bobo driving school, the business he started after Volta Jazz split up.

The music of Volta Jazz is infectious and filled with joy. Even if you don’t understand the Jula language in which it is sung, it is a distillation of delight. Some of their songs focus on local stories, like “Baba Moussa,” which celebrates a police lieutenant who apprehended an Ivorian thief who stole one of the band member’s suitcases at the train station. “Baba Moussa had done a good job, and we made a song to thank him,” Traoré told me. Other songs focus on the country’s leap into modernity: one is a jingle commissioned by the new national airline, Air Volta. As the band became more popular, it toured around the country by minibus, and occasionally travelled to other parts of West Africa: Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, and Ghana.

The scene the group inhabited was thriving, and constantly metastasizing. “We were the best, but there were lots of orchestras in Upper Volta during that period,” Koné told me. Mazzoleni’s box set includes work by other orchestras (my favorite after Volta Jazz is Les Imbattables Léopards—“The Unbeatable Leopards”). The number of bands sparked intense competition, and Volta Jazz had to constantly innovate to stay ahead. Another band on the box set is L’Authentique Dafra Star de Bobo-Dioulasso, which was founded in the late nineteen-seventies by a member of Volta Jazz. He thought their music had become old-fashioned, so he split off with a handful of his fellow-musicians and mixed Cuban tumba drums into his own compositions.

Bil Aka Kora, a successful Burkinabe musician, told me that Volta Jazz was incredibly influential to the generation of musicians that followed them. “It was really one of our precursors as fusion musicians. They played modern music but they were mixing in a lot of our traditional rhythms, it was really important for us,” Aka Kora told me. “When we were small, six years old, me and my friends would enter in bars through holes in the walls, or by sneaking in through their bathrooms, to watch them play. At that moment, Burkinabe music was really well represented in Africa and also further abroad. I think that it was them who gave us musicians, us young people, the desire to play music with modern instruments.”

The band’s high point, both Koné and Traoré remembered, came in 1967, when the band took first prize at a large national musical competition with foreign bands at the Maison du Peuple, in Ouagadougou, the country’s capital. The song that led them to victory is called “The Prayer of Volta Jazz,” (on the Bobo mixtape, it’s called “Fintalabo”) a crescendoing piece of distilled excitement. Traoré played it to me on a small speaker and explained the lyrics. It begins as a prayer for rain: “God of the sky and the earth and everything, the sick and the well, the King of Kings, I ask you, in your power, to give us beautiful rain on our land. With that, the peasants will be able to eat.” The drums start beating more quickly, the music swells. The singer asks God for a “good collaboration with white people.” At that point, the foreign musicians in the room at the Maison du Peuple jumped to their feet and everyone followed. “That’s the part where everyone started singing. The part that won us the prize itself,” Traoré said. “Ah, you’re making the memories come back.”

Another son of Bobo-Dioulasso was Thomas Sankara, who trained as an army officer and quickly transitioned into leftist politics. In 1984, at the age of thirty-three, he led what he called a “democratic and popular” revolution against Burkina Faso’s old corrupt order. As the President, Sankara changed the country’s name to Burkina Faso (the name means “land of the upright people”) and pursued land reforms, mass vaccinations, and education programs that increased the country’s literacy rate by sixty per cent in three years. He also began cutting ties with the French, who had largely continued to exploit Burkina Faso’s resources after decolonization.

The French government, sensing socialism in Sankara’s collectivist strategies and fearful of the ideology’s spread in Francophone Africa, exploited political divisions in its old colony. In 1987, Sankara’s chief adviser and confidant, Blaise Compaoré, led a coup, ordering the shooting of the President in his office and forcing his family into exile. The coup began Compaoré’s twenty-seven-year rule, marked by the elimination of Sankara’s supporters, close ties to the French, as well as rampant corruption and the siphoning off of the country’s resources. (Burkina Faso has recently asked the French government to declassify documents on Sankara’s death; Compaoré maintains he was not involved in Sankara’s death.)

“Je Vais Décoller,” 1977.

Photograph by Sanlé Sory. Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery

Culture was one of the first casualties of the political upheaval. Sankara enforced curfews and laws that prohibited bands from charging money for concerts. Orchestras like Volta Jazz’s businesses were undercut. Then, as corruption rose under Compaoré, fewer people had money to spend on entertainment. Eventually, Koné shifted his focus to his driving school, where Traoré joined him.

But a reading of Volta Jazz’s history that ascribes its downfall solely to political factors is not entirely accurate, either. The band was also a victim of trends in the music industry. As the nineteen-eighties progressed and individualism supplanted collectivism, the focus shifted onto popular solo artists. I asked Koné if he thought he might ever re-form Volta Jazz. “Today it’s all individual stars,” he told me. “It’s evolution.” When I asked Traoré the same question, he showed me his set of stiff and swollen fingers. “With what hands?” he laughed. “To play guitar, you need to quickly move your fingers.”

But even popular solo artists like Aka Kora lament the passing of the orchestra tradition and the high regard that went along with it. “Burkinabe music isn’t as represented in Africa these days like it was, even in the sub-region,” he told me during a break in a recording session in Ouagadougou.

Sory says he’s also been a victim of the times, despite his recent success at exhibitions in New York and Europe. One of his wives is paralyzed, and he does little work as a photographer these days. With the advent of digital photography, the number of photo shops in Bobo has dwindled.

I end my trip to Bobo with a visit to Sory’s current Volta Photo studio. It inhabits a tiny hotbox of a room off a main street since his landlord died and his sons raised the rent on him. It’s a shadow of what it once was. He clanks open a metal door and shows me the studio, a blue sheet hanging behind boxes of equipment. He agrees to sit for a few photos and then chides me: “Are you sure they’re going to come out in this gloom?” (They did turn out a little blurry, but I like them nevertheless.)

Throughout our time in Bobo, Sory insists that he’d be able to take photographs as he once did if only he had access to photographic material and a willing client base. “If you gave me the right paper and chemicals, I could make pictures again,” he insists. “What’s weird here is that nobody likes black-and-white pictures here anymore. It’s a shame. They want color pictures,” Sory tells me. “In our time, there were no problems. Now there are lots of problems; people are more demanding with what they want in their pictures,” he continues. In many ways, their demands echo trends originally sparked by colonial-era ideas about race and whiteness. “When people compare black-and-white pictures to color pictures they say, ‘I’m too black in this one.’ People want to look white. What I say is that you should be the way you are.”

Sourse: newyorker.com