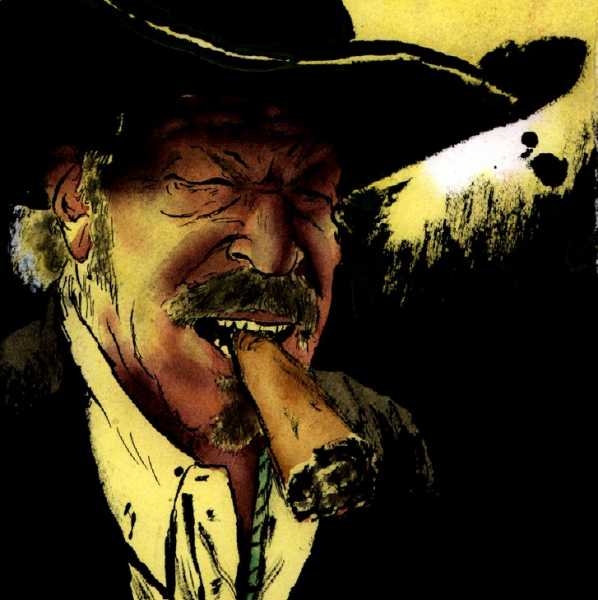

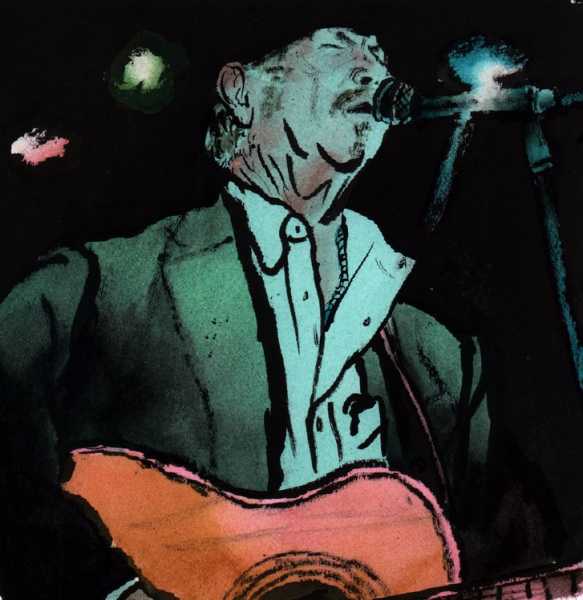

“Some of the stuff I’ll be doing tonight I’ve only done a few times on stage,” the country musician, mystery novelist, and former gubernatorial candidate of Texas, Kinky Friedman, warns, with his deadpan, mellow rasp. “So I might screw up. It’s possible. And if I do you’ll know because I usually go, ‘Fuck.’ ”

Kinky has been on the road all summer, quietly touring in support of “Circus of Life,” his first new album of original songs in more than forty years.

“Now, in Europe, when I screwed up, they loved it,” Kinky adds, as he begins to strum. “They all felt it was performance art. The audience here has no sense of that. They don’t think it’s performance art. They just think I’m a little fucked up.”

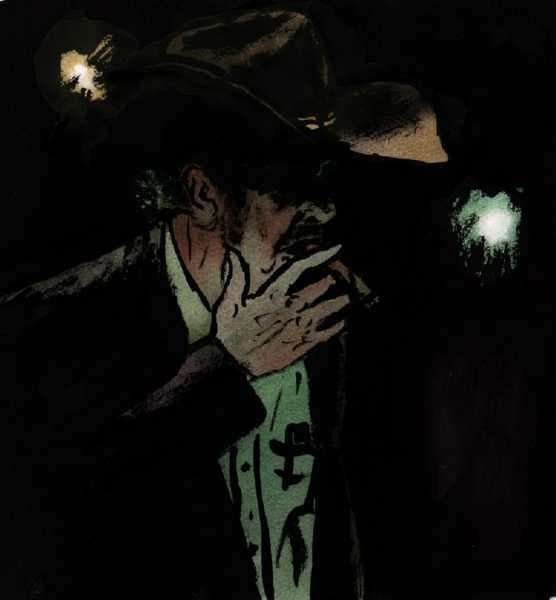

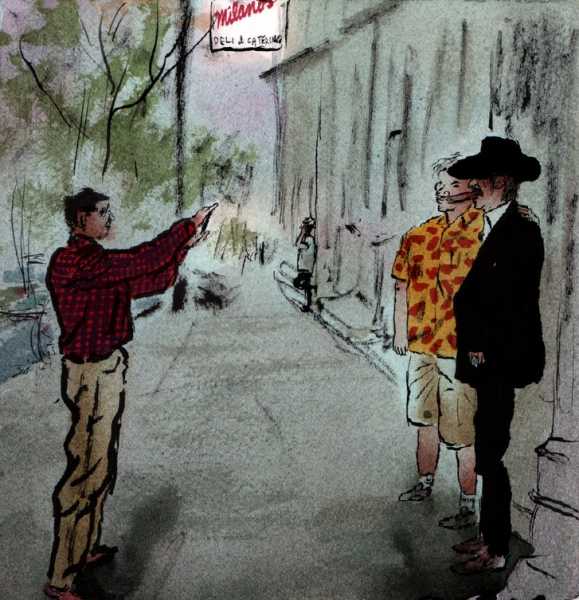

On a recent visit to perform at City Winery, Kinky stayed with his friend Ryan (Slim) MacFarland and his family, at their home, in Jersey City. “What’s it like having Kinky Friedman as a house guest?” I ask Slim.

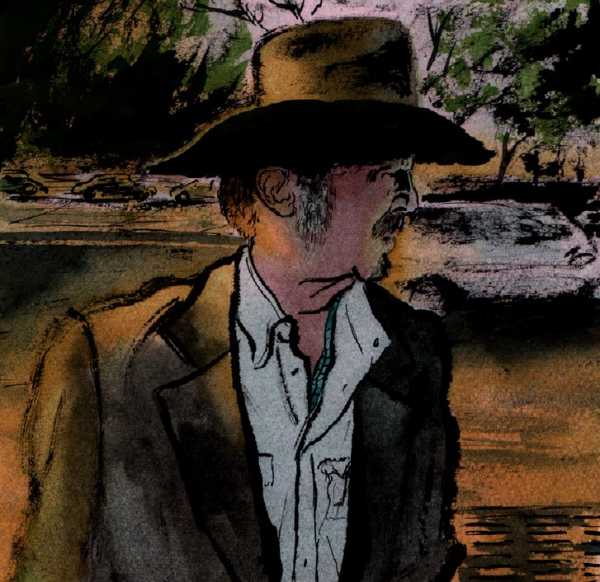

“As soon as Kinky walked in the door, with his black Stetson hat and ostrich-skin boots,” Slim recounts, “my five-year-old daughter was in awe. He squatted to meet her at eye level, tipped his hat, and asked if she had ever seen a real cowboy before. She loved it.”

Kinky isn’t, in fact, an actual cowboy. But he is a genuine showman, whose credits as a musician include a stint on tour with Bob Dylan, during the 1976 leg of his “Rolling Thunder Revue,” a travelling caravan of featured performers that included Joan Baez, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Roger McGuinn, Joni Mitchell, and Bob Neuwirth.

“For Kinky,” Slim continues, “life is the performance. So he’s always on: the cigar’s in his hand, maybe he slept in his clothes . . . ”

“ . . . and he’s knocking on your door asking if you want coffee at some ungodly fucking hour, telling you that you’ll drink it black because that’s how they drink it in Texas . . . ”

“ . . . and then he’s bringing you a cup of dirty black coffee, and you’re gonna drink it, and he’s gonna sit there and talk to you and blow cigar smoke right in your face and you’ll just deal with it because he’s funny and irreverent and you love what’s coming out of his mouth.”

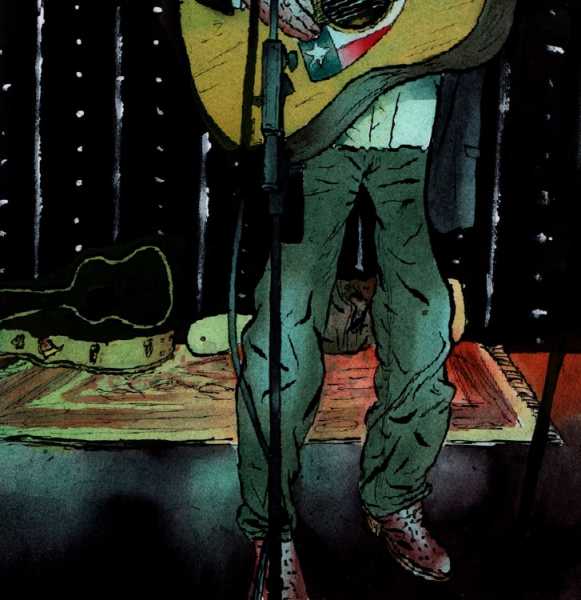

Onstage, Kinky exhibits similar traits, minus the smoke. The next night, in Jersey City, at the comparatively diminutive Monty Hall, a music venue owned and operated by WFMU, the local public-radio station, Kinky introduces “Waitret, Please, Waitret,” from 1976’s “Lasso from El Paso,” his last album of original material. In the song, a customer politely invites a waitress to “come sit on my fate.” After one verse, the unfashionably misogynistic tune is abandoned, despite the cautious laughter of the predominantly middle-aged and older crowd. “Well,” the Kinkster, as he is also commonly referred to, especially in the third person, proclaims, “you get the drift.”

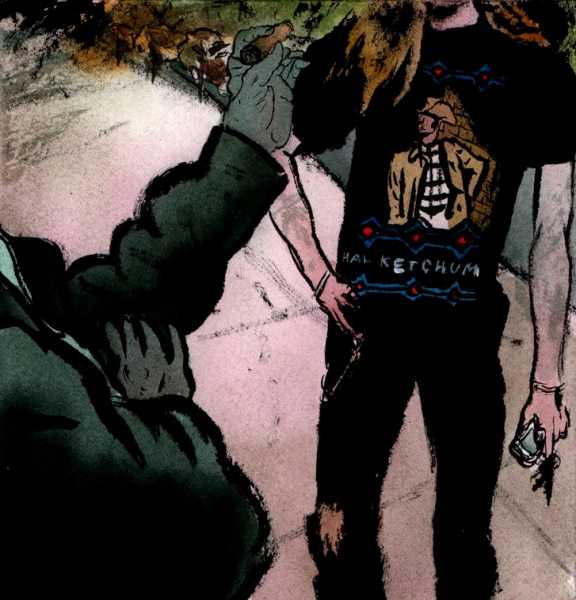

“You know, a lot of people, when they think of Kinky Friedman,” McFarland says, “they think of songs like ‘They Ain’t Makin’ Jews Like Jesus Anymore,’ ‘Get Your Biscuits in the Oven and Your Buns in Bed,’ and ‘Asshole from El Paso.’ The funny shit. But Kinky mostly writes serious, heartfelt songs.”

Before launching into “Ride ’Em Jewboy,” which has a funny title but is undoubtedly his most serious song of all, Kinky (who is proudly Jewish) regales the audience with a seeming tall tale. While on a book tour of South Africa, in 1996, Kinky met the anti-apartheid activist Tokyo Sexwhale (pronounced “sex-wah-lay,” but spelled, as Kinky pointed out, “Sex Whale”), who was imprisoned in a cell beside Nelson Mandela on Robben Island. Every night for three years, Sexwhale told Kinky, Mandela listened to “Ride ’Em Jewboy,” the first song of the rock era to be written about the Holocaust, from a smuggled cassette of Kinky’s début album, “Sold American,” from 1973.

“Ride, ride ’em Jewboy

Ride ’em all around the old corral.

I’m, I’m with you boy

If I’ve got to ride six million miles.”

Toward the end of the evening, Kinky puts down the guitar in favor of a copy of “Heroes of a Texas Childhood,” one of more than thirty books that he has written that isn’t a mystery novel, to read “The Navigator,” a story about his father. “He taught me chess, tennis, how to belch, and to always stand up for the underdog,” Kinky explains before reading, “as well as the importance of treating children like adults, and adults like children.”

Although Kinky has been out of the political limelight since his unsuccessful bid to become the Texas agriculture commissioner, in 2014, he has not forgotten how to campaign. “My definition of politics still holds,” Kinky asserts. “ ‘Poly’ means more than one, and ‘tics’ are blood-sucking parasites.” At the end of the show, Kinky descends into the audience to graciously shake as many hands as possible as he leads the satisfied mob to the merch table in the lobby.

It was a 3 A.M. telephone call from another one of Kinky’s lofty friends, Willie Nelson, that inspired “Circle Of Life.” Kinky was watching “Matlock.” Willie, who Kinky also refers to as his therapist, instantly diagnosed his friend with depression and prescribed him to pick up the guitar and write. “When it was all over, and we were done with the record,” Slim recalls, “and Kinky heard it for the first time, he said, ‘Slim, you’ve made a senior citizen very happy.’ ”

Sourse: newyorker.com