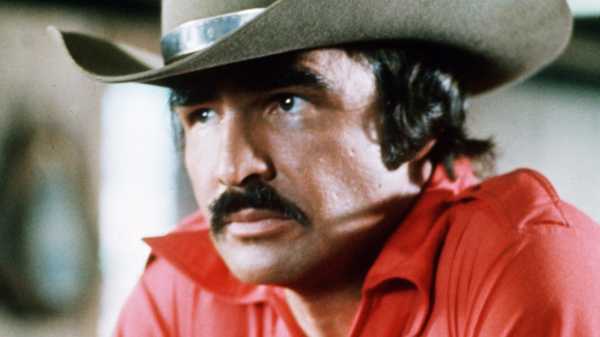

For pop-culture enthusiasts of the seventies and eighties, news of the death of Burt Reynolds, at age eighty-two, of a heart attack, in Jupiter, Florida, may have come as an unexpected shock. Some of us imagined him as eternally youthful, wisecracking, knowingly amused. Reynolds was a genial presence who seemed to have it all—in his heyday, he was the country’s top box-office star for five years; later, he lived in a sprawling estate called Valhalla—and remain a good sport. (His memoir, from 2015, is called “But Enough About Me.”) He was an amiable king of machismo, hairy chests, and highway-focussed buddy comedies, and his friendly sexiness—onscreen and on the covers of tabloids and glossy magazines—was for many years a constant. His groundbreaking centerfold in Cosmopolitan, from 1972, in which he stretched out, naked, on a bearskin rug, embodied his affable sensuality. “He was handsome, humorous, wonderful body, frisky,” Helen Gurley Brown later said, of choosing him for the shoot.

Reynolds was born in Michigan in 1936. He was a star football player at Florida State University; after an injury, he dropped out and moved to New York to become an actor. (Late in life, he went back to school.) After performing in a New York production of “Mister Roberts,” he got a TV contract, and in the next three decades appeared in dozens of rugged roles in Westerns, adventure movies, cop shows, and other brawny fare, including “Gunsmoke,” “Riverboat,” and “Hawk,” in which he starred as an Iroquois New York City detective. He hit his stride in the seventies, beginning with his breakout role as Lewis in “Deliverance,” in 1972. In 1977, “Smokey and the Bandit” made him an icon to kids, too. He played the Bandit, half of a duo that scrambles to bring a truckload of bootlegged beer from Texas to Georgia, joined by a runaway bride and pursued by a sheriff named Buford T. Justice. (In a famous scene, set to fiddle music, Reynolds, driving a black Trans Am, casually jumps a bridge with Sally Field squealing in his passenger seat. They subsequently dated for several years.) There were two sequels, just as Southern-fried, one involving a song recorded by Reynolds, “Let’s Do Something Cheap and Superficial,” that became a modest hit. And in “The Cannonball Run,” a bonkers, all-star affair, Reynolds chews gum while speeding an ambulance containing Farrah Fawcett from New York to California. (The gum chewing, and the rascally insouciance, dominated Norm MacDonald’s “S.N.L.” impressions of him.)

Reynolds remained lovably roguish throughout that tire-screeching era; I was startled to rewatch “The Cannonball Run” years later and remember how much time he spends slapping Dom DeLuise and calling him a blimp. There and beyond, it was a hearty decade-plus of wailing sirens, flying V-8s, and cars getting sheared in two while somebody yells “dangnabbit.” And, all along, Reynolds did his own stunts. In “Stroker Ace,” from 1983, he played a NASCAR driver who clashes with a fried-chicken magnate. The film was a flop, but he co-starred with Loni Anderson, whom he married. (If you were a fan of “WKRP in Cincinnati,” you were likely also fond of Anderson, who seemed like an apt match for Reynolds—they both radiated a warm and earthy stardom. The marriage, which ended in divorce, seems to have been less fun than I imagined; Reynolds later lamented not marrying Sally Field.) In the eighties and nineties, Reynolds’s career downshifted in influence but chugged along in productivity; he worked steadily throughout his life.

In 1997, Paul Thomas Anderson’s poignant, improbably sweet seventies-porn opus “Boogie Nights” returned Reynolds to us, older and wizened and handsome as ever, in the role of a director who brings Mark Wahlberg’s well-endowed innocent into a celluloid world where he rises, falls, and finds a ragtag, triple-X family, of which Reynolds is the patriarch. (“I make … exotic pictures,” he says to Wahlberg, with a smirk.) Reynolds looked right at home; there was something touching about seeing him, polyester-clad and sympathetic—if exuding a hint of manipulative, amoral sleaze—comfortably owning the era whence he came. He was nominated for an Oscar for the role, and that felt right, too.

And still he chugged on. This year, in a move that now feels, uncannily, like foresight, Reynolds featured in Adam Rifkin’s “The Last Movie Star,” which was written for him. He plays an aging, cane-wielding film icon receiving a somewhat humble lifetime-achievement award. “An audience will forgive a shitty Act II if you can wow ’em in Act III,” he says at one point. In a charming conversation with Kathryn Shattuck in the Times earlier this year, Reynolds says of the film, “I liked it. It was very different than anything I’d done. There weren’t any cars or things jumping other cars or girls and stuff.” He also recounts a lovely memory of an evening with Elaine Stritch, and the greatness of her renditions of Sondheim’s “I’m Still Here,” from “Follies,” the ultimate lifetime-in-showbiz anthem. (“Black sable one day, next day it goes into hock, but I'm here / Top billing Monday, Tuesday you’re touring in stock, but I’m here.”)

“Elaine Stritch, boy, could she sing that song,” he says. “I went out with her one night. It was just for fun, but we had the best time, laughing and giggling. And I’m saying good night to her, and I said, ‘Elaine?’ And she said, ‘Yes?’ as she was walking away. And I said, ‘I’m still here.’ And she said, ‘So am I, hon.’ ”

Sourse: newyorker.com