Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Jagdish Photo Studio in Manori came to Ketaki Sheth like a vision. A photographer from Mumbai, Sheth owns a house in a coastal village about 40 miles north of the city, and had made countless visits there without even knowing the studio existed. One afternoon in 2014, she was shooting with a Leica M9 when she stumbled upon the establishment, squeezed between an old grain silo and a hardware store—“a pretty nondescript little place,” as Sheth recently put it. The counter attendant explained that it was the only place in the area where customers could have their photos taken for their Aadhaar cards, the biometric identification issued to almost all adults in India. Sometimes, the attendant mentioned, people would come in for portraits to mark special occasions or festivals. Sheth was intrigued. “Are you expecting people today?” she asked.

Studio 786. Cuttack, Odisha, 2016.

Jagdish was the first of more than sixty-five studios across the country that Sheth would photograph over the next three years. The resulting Photo Studio series, later published as a book of the same name by Photoink, marked a departure from the black-and-white, analogue documentary style she had used in previous projects, including street shots of Mumbai and visual ethnographic portraits of twins and the Siddis, an Afro-Indian ethnic group.

Babas Studio. Trivandrum, Kerala, 2016

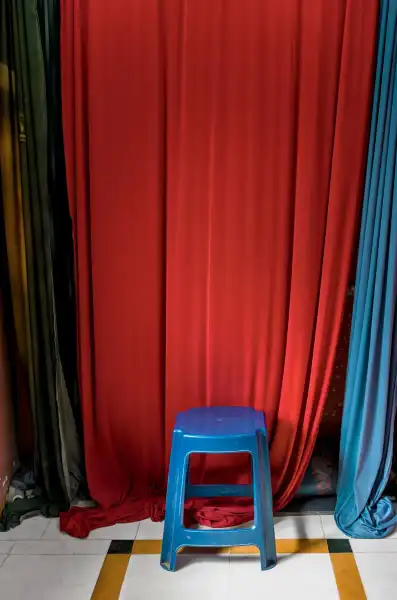

Portrait workshops, she decided, required a more vivid treatment: for the first time, Sheth was shooting in colour. The brightness of her photographs contrasted with the fading role of the business in Indian life. In the age of smartphones, formal portraiture had fallen out of fashion, and studios like Manori were on the verge of closing. Sheth told me, “Either the road gets widened and the government pays the owner compensation to go away, or a developer comes in.” Most of the remaining owners’ sons and daughters had no interest in continuing their parents’ business. One owner, in Hyderabad, had lost the artist who created his ornate backdrops to a Middle Eastern patron. But some of the places Sheth visited showed signs of a flickering heyday. Shelves were still lined with stacks of photographic plates and old boxes of Fujifilm printing paper. A Mumbai film studio still has tungsten lamps that once illuminated portraits of Indian cinema's most revered stars.

Tara Studio. Ramanathukara, Kerala, 2016

Victory Photo Centre. Hyderabad, Telangana, 2016.

Krishna Digital Photography Studio. Jaipur, Rajasthan, 2016.

Tara Studio. Ramanattukara, Kerala, 2016

Moti Art Studio. Ajmer, Rajasthan, 2016.

In each city, Sheth asked locals to pose against the trappings of this vanishing world. Many modern studio photographers favor the simplicity of Photoshop: newlyweds attending a wedding shoot might opt for digital manipulation against the Eiffel Tower, the Taj Mahal, or the Egyptian pyramids. But sometimes Sheth would find exquisite hand-painted backdrops in storage and use them. (Sheth learned that several new studios had outsourced the work to a company in Punjab that specialized in mass-producing painted canvas backdrops.)

Jagdish Photo Studio. Manori, Maharashtra, 2015.

Tara Studio. Ramanathukara, Kerala, 2016

Babas Studio. Trivandrum, Kerala, 2016

Sitaram Digital Studio. Bhavnagar, Gujarat, 2016.

Jagdish Photo Studio. Manori, Maharashtra, 2015.

In Sheth’s photographs, the backdrops of the subjects seem almost like fairy-tale landscapes or portals to distant universes. In Kerala, two pensive boys lie on the shores of a tranquil azure lake, with snow-capped mountains in the distance. Behind two hijab-wearing manori women, an Ionic column evokes an ancient Greek temple. A farmer in Rajasthan poses in front of a sequined curtain that resembles a glittering galaxy of stars. Other shots focus on the shabby interiors of businesses or their outdated props and tools: a statue of Mahatma Gandhi, the oldest tripod Sheth has ever seen. Her work, featured in the recent exhibition “Staging” at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, not only pays homage to Indian photography studios, but also references the work of local portrait photographers like Mike Disfarmer and Seydou Keita, who turned their everyday work into art.

Phototec Studio. Calicut, Kerala, 2016.

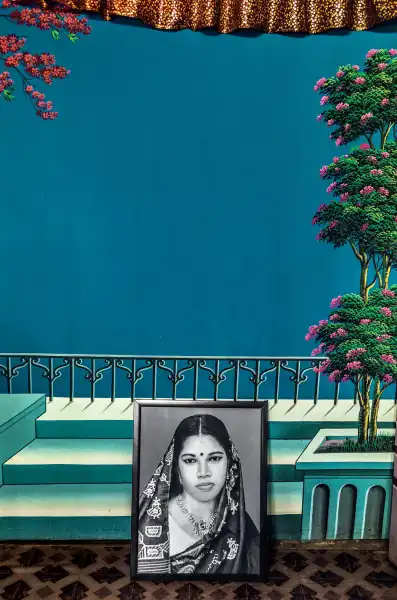

While browsing the shelves of a studio in Odisha, in eastern India, Sheth noticed a black-and-white photograph hanging on the wall. It was a portrait of the owner’s late mother as a young woman, wearing an intricate pendant. “Could you take this down?” Sheth asked. She created a makeshift altar, placing the framed image on a painted backdrop that depicted a balcony overlooking a blue sky, evoking the afterlife. Sheth’s project was another way to honor previous generations. At Vanguard Studios in Mumbai, Sheth came across boxes full of glass negatives—receptacles for the countless anonymous models who had once frequented the establishment. Photos of such ephemeral objects are scattered throughout the book. In the caption to one negative, in which the couple pose in formal attire – the husband in a loose 1950s suit, the wife in a sari – Sheth writes: “Do their grandchildren know they still exist on glass?”

Singh Studio. Anandpur, Odisha, 2016.

Sourse: newyorker.com