Save this storySave this storySave this storyYou're reading Infinite Scroll , a weekly column by Kyle Chayka about the impact of technology on cultural processes.

On a quiet weekday morning in Manhattan, I set out to get my hands on a Laboobu, the cute little doll monster that has become the biggest global toy trend since the Beanie Babies craze of the late 1990s. The collectible figures, popular with kids and adults alike, were designed by Hong Kong designer Kasing Loong in 2015 and mass-produced by Chinese manufacturer Pop Mart in 2019. In 2024, K-pop star Lisa began sharing her collection on social media, sparking a surge in demand. Laboobu feature pointed teeth, bunny ears, and wide, glittering eyes. Their faces and limbs are smooth, while their rounded bodies are covered in a furry texture. The creatures are often found adorning phones or bags—like tiny demons haunting accessories—or clutched in hands like miniature pets. They come in over three hundred variations, allowing you to choose an image to suit your style or mood: pink fur for coquetry, glowing red eyes for boldness, the Dress Be Latte scarf for coziness. At the prestigious Art Basel fair, a limited edition of Labubu art pens was released, which sold out in twenty minutes. The scarcity of Labubus makes them unavailable both online and in stores. It was this unattainability that ignited my desire – perhaps the owners have secret knowledge. So I found myself in the Partea cafe on Union Square, where neon machines are filled with boxes of Labubus. I decided to try my luck in trying to get my own monster.

A friend and I ordered drinks—sparkling grape yogurt and iced vanilla mousse with green tea—and exchanged twenty dollars for twenty tokens for four tries at winning a grinning Labubu from a glass machine. Despite the early hour, there were teenagers and adults gathered around, eager for the same prize. I inserted the tokens and pointed the claw at the holographic container. (Labubu are sold in opaque “blind boxes” that conceal their rarity.) The claw grabbed the box, lifted it, and then dropped it. Three more tries only added to the frustration. (I later learned that the grip was random.) A new Labubu costs about as much as I had spent, so I decided to stop. No one had won a single one in the entire time at the cafe. The images of the dolls on the packaging flickered, as if mocking our failure.

Why did I even need this toy? It seemed like a lifestyle item I’d missed out on — a world of physical objects that have become online fandoms, status symbols that combine Instagram aesthetics with consumerism. But the style has turned out to be centered around weird, sometimes creepy things: Dubai chocolate with pistachio cream and phyllo dough oozing with pea paste; matcha lattes in deep green hues, sometimes with strawberry syrup that resembles blood splatters; Crumbl cookies with lemon-berry filling and pastel icing. “Crystal” mugs have been making the rounds online, only to turn out to be fakes with cloudy resin instead of crystals. Jelly shoes that resemble fossilized seaweed are trending, and brands like Tyler McGillivary are printing giant insects and mushrooms onto their clothes.

These products seem to be born of hallucinations. They take the idea of self-transformation through social media to the point of absurdity, using chemical additives and digital tools: we improve ourselves until we become something else. The aesthetics here are a defense against the digital age and an irony about it. “Everything looks deliberately unnatural,” notes cultural scientist Dean Kissick. Any claim to naturalness is destroyed by artificial elements: peptides in Rhode lip gloss, collagen in Erewhon smoothies, Touchland disinfectants with the scent of “Power Dew,” Ozempic in green Hers bottles reminiscent of matcha. Memes are now consumed physically. It is reminiscent of Donna Haraway’s “Cyborg Manifesto”: a hybrid world where the boundaries between the biological and the digital are erased. Labubu are our avatars in the era of disintegrating norms.

Toy trends are nothing new: Furbies from the 1990s were also considered devilish. Online memes have long permeated reality: “digital lavender” as the color of 2023, latte art, and millennial coworking spaces. But current Gen Z trends combine generative AI, biohacking, and digital aesthetics. Their “ugliness” is a feature, not a flaw. The recent viral hashtag #Labubumatchadubaichocolate captures the spirit of the times: artificiality as the new norm. Meaninglessness here is a conscious gesture.

At Bloomberg, Amanda Mull attributes this phenomenon to algorithms and globalization, where brands lack depth. In The Blank Space, W. David Marks writes that memes exist as narratives and objects that have become mandatory to know. But the scale and interconnectedness of these products matter more than momentary hype. They are tools for adapting to a reality where the body and image require constant editing, and magical thinking helps us survive in a world of uncertainty.

IRL Brain Rot is a culture of physical artefacts that are inseparable from the digital context. Changing Labubu dolls is like changing avatars; memes become talismans. “Brain rot,” Oxford’s 2024 word of the year, includes absurd memes like “Skibidi Toilet,” “rizz,” and “delulu.” As linguist Adam Aleksic notes, the term mocks the dominance of algorithmic trends, but also serves as a form of self-defense. The combination of niche memes (“microbrain rot”) confirms belonging to a common information environment. Algorithms capture subconscious preferences; sharing tastes with friends creates the illusion of a shared reality. The answer to digital overload is to embrace it, like Oscar the Grouch in the trash.

No single object can convey the breadth of the algorithmic feed that influences fashion, food, and social interactions. “You need a whole bunch: peptide glitter, Benson Boone cookies,” says trend expert Casey Lewis. Combinations amplify the effect: Starbucks customers mix matcha with pistachio syrup to create an underground version of Dubai chocolate. The color scheme is sludge-like, perfect for the Brain Rot era.

The Italian version of Brain Rot is the latest trend: viral animations featuring hybrid creatures like the three-legged shark Tralalero Tralala or Tung Tung Tung Sakur. Writer Bruce Sterling discovered them in Mallorca, in blind boxes similar to Labubu containers. The Boneca Ambalabu doll (a frog head on a tire with legs) reminded him of early cyberpunk: “It’s a trial balloon for the invasion of AI ugliness offline.” Technologies often debut as toys, harmless until they get serious.

IRL Brain Rot is an almost radical aesthetic movement. If pop culture is stuck in superheroes and beige, these objects exist in a Baudrillardian hyperreality where the digital is primary. Their “tastelessness” is a source of strength. “Artists no longer set trends,” says Kissick. The avant-garde is born in the internet underground, as he writes in his essay “The Vulgar Image”: NFTs with pixelated decay, AI videos with distorted faces. “Bad taste stands out against the background of information noise,” he says. Ugliness can be a resistance to the cult of optimization: being monsters, there is no need to strive for perfection. Ozempic is like Photoshop for the body.

Embracing hybridity is acknowledging that nothing is pure. Our bodies contain microplastics, vape residue, ketamine. Our brains are saturated with digital garbage. If culture has reached a bottom of meaninglessness, where ideas are just fuel for engagement, the only way out is to walk through it. As Haraway advised: with relish.

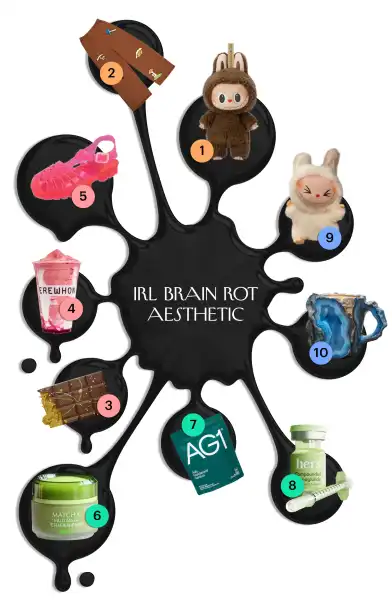

The charm of the grotesque: The usual aesthetics are boring; the trend is flashy and oversaturated. Labubu (1) with neon fur decorates luxury accessories. Tyler McGillivary (2) completes the look with mushroom prints. Laconicism is out of place.

ESSENCE: Everything is fluid and excessive. Dubai chocolate pistachio cream (3) flows from a geometric shell. The ingredients of the Erewhon smoothie (4) are pointedly not mixed. The 1979 Jelly Shoes (5) are petrified, symbolizing everything jelly-like.

GREEN EPIC: Matcha is a symbol of energy and premium. It is added to face masks (6) , AG1 powder (7) , Hers Ozempic generic (8) in a green bottle. Health has become a status.

FAKES: Global manufacturing spawns clones: fake Lafoufu (9) , Hims medicine, AI mugs (10) with resin drips. This is a leak of digital garbage into reality.

Brain Rot is not always a successful experience. After the machine failure, my friend and I were walking around Union Square. Street vendors were selling knockoffs of Laboubu (Lafufu), but I was drawn to the real thing. Then we saw an ad for Dubai Chocolate on a souvenir shop. Inside, instead of a bar, they were selling a pistachio-chocolate dessert with knafeh. The matcha sauce was sold out. The baker recommended a mix of all the ingredients. For fifteen dollars, I got a green-brown-red mass.

At a sunny table, a friend remarked, “It looks like it was dropped in sawdust.” The taste was cloying, with a pistachio aftertaste. Only the strawberries seemed real. Sunday was too ugly for Instagram, which was probably the point: he existed only as a materialized meme. I walked around all day, filled with a strange energy. Either I was tapping into the zeitgeist, or I had too much sugar. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com