Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

For several weeks each August, the Edinburgh International Festival and Edinburgh Festival Fringe fill the theatres, student centres, lecture theatres and pubs of the Scottish capital with a diverse range of performances. Guests and performers are invited to fully immerse themselves in the event: I saw twenty-eight performances over six days – I know more gifted and energetic people might have seen more – and, while hurrying down a picturesque cobbled street, I also witnessed three drunken lads unerringly puking in perfect synchronicity. (My companion discreetly pointed out that Oasis was in town.)

Despite the Dionysian frenzy, which wasn’t just drunken but often pleasant and sociable, I found this season particularly unsettled. There was widespread talk that Edinburgh accommodation prices had skyrocketed after Oasis announced part of their tour for the first half of the Fringe (in turn, Oasis’s Liam Gallagher described the festival as “people juggling bullshit and stuff”), and it was hard not to notice that some long-standing festival fixtures, like producers Paines Plough, had reduced their usually high-profile presence to a handful of shows.

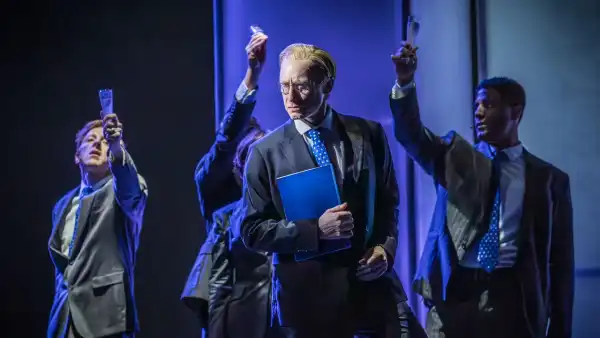

The highlight of the month – and the International Festival’s key event – is James Graham’s Make It Happen, a retelling of the 2008 collapse of the Royal Bank of Scotland, which was for a time the richest bank in the world. Graham portrays the bank’s arrogant CEO Fred Goodwin (Sandy Grierson) as a character from a Greek tragedy: a choir sings slow-motion pop songs whenever he contemplates a particularly fraudulent spending spree, and he is visited by the disapproving ghost of Adam Smith, the Scottish proto-economist and “father of capitalism”, played with light humour by Brian Cox. The plot is as shallow as a pantomime script – “Your proposal document, Fred, is brilliant,” says one star-struck staffer – and takes a strangely maudlin stance on the Scots financier’s culpability. Even after Graham demonstrates the bank's incredible greed, he ends the play with Goodwin looking hopefully to the horizon as a chorus boy carries a metaphorically laden sapling (a young plant!) on stage. Does Goodwin really need this cloying quasi-redemption? I checked, and he's still getting a pension from the Royal Bank of Scotland of six hundred thousand pounds a year.

But of course, that’s what Make It Happen is all about – making us reconsider, making us look back. Graham’s play, like so many this year, is both a testament and a reminder. In the recent uproar over controversial memorials and whether they should remain or be torn down, we rarely notice that fake Doric columns or giant equestrian statues are poor reminders of our history. Plays can make us stop and remember; monuments allow us to pass by and forget.

Many of the best productions I saw at the Fringe were living memorials to horror. Sometimes the desire for accuracy turned these shows into political statements, whether they were intended to be so or not. The great comic activist Mark Thomas, who played Frankie in Ed Edwards’s one-man prison drama The Ordinary Decent Criminal (one of two Paines Plough features), was so adept at espousing socialist solidarity with the IRA that he literally broke the fourth wall when railing against an Irish Orange Order march in a park outside the theatre. “Now back to the script,” Thomas said, shaking his fist. Comedian Nish Kumar, who delivered a brilliant, laugh-out-loud hour-long stand-up routine called “Nish, Don’t Kill My Vibe,” reminded viewers of both Boris Johnson’s breaches of Britain’s Covid lockdown laws and the royal family’s refusal to return the Koh-i-Noor diamond. (“I didn’t pay attention to the old lady,” he said, referring to the Queen. He’s clearly less fond of Charles.)

Niall Moorjani’s play Cawnpore: 1857 actually describes an existing monument, still standing on the esplanade of Edinburgh Castle, erected to honour the men of the 78th Highland Regiment who died in what became known as the Indian Mutiny. But no complete story is set in stone. Moorjani’s character – a mutineer strapped to a cannon, desperate to please a cheerful, cruel British officer (Jonathan Oldfield) – highlights the difficulty of accurately telling the story of the war. The mutineer describes the massacre of hundreds of British women and children by revolutionaries; they also describe the subsequent reprisals by the colonised

Sourse: newyorker.com