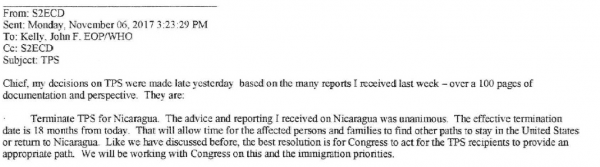

At 3:23 pm on November 6, 2017, Elaine Duke — then the acting homeland security secretary — sent an email to White House Chief of Staff John Kelly. She was hours away from a midnight deadline on extending or ending Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for more than 5,000 Nicaraguans who had been in the US since 1999, and she had finally made her decision: She was going to end TPS for Nicaragua and force the beneficiaries to leave the US or risk deportation, but not until July 5, 2019.

“The effective termination date is 18 months from today,” Duke told Kelly. (In reality, it was 18 months from January 2018, when Nicaraguans’ protections were set to expire without a renewal.) “That will allow time for the affected persons and families to find other paths to stay in the United States or return to Nicaragua.” Duke’s chief of staff, Chad Wolf, forwarded the decision to White House Homeland Security Adviser Tom Bossert.

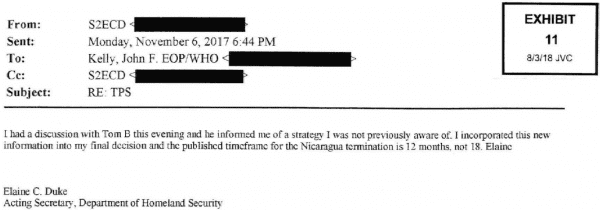

Three hours later, Duke sent Kelly another email: She had changed her mind.

“I had a discussion with Tom B this evening and he informed me of a strategy I was not previously aware of,” she wrote. In light of this “new information” from the White House, she’d shortened the grace period for Nicaraguans from 18 months to 12 — forcing them to leave the country or risk deportation by January 5, 2019.

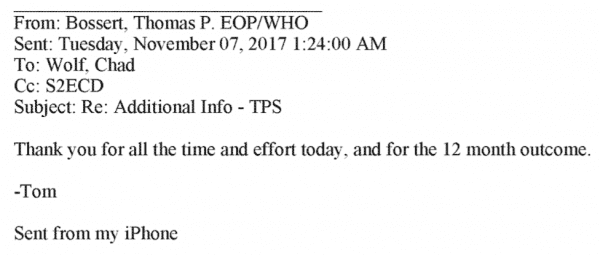

Bossert emailed Duke’s chief of staff later that night: “Thank you for all the time and effort today, and for the 12 month outcome.”

Duke’s last-minute change — and the White House’s role in engineering it — came to light last week in a federal lawsuit challenging the Trump administration’s decisions to end TPS for hundreds of thousands of people. (In addition to 5,000 Nicaraguans, the administration will strip protections from 58,000 Haitians, 260,000 Salvadorans, and 87,000 Hondurans in the year between January 5, 2019 and January 5, 2020.)

The executive branch has broad authority to grant TPS, and to decide whether or not to extend it for any given country. But that decision is supposed to be based on the conditions in the country in question, and it’s supposed to be made by the homeland security secretary herself.

The lawsuit, filed by a group of TPS holders and their US citizen children (with assistance from the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California and the National Day Laborers Organizing Network), accuses the Trump administration of making the decision to strip TPS from Nicaraguans and others to advance its own immigration agenda — and reverse-engineering its analysis to match the strategy dictated to them by the top.

The Washington Post and other outlets reported on emails published in the lawsuit that show political appointees at DHS editing reports about “country conditions” to better support the recommendation to end TPS protections. But the last-minute change to the timeline for Nicaragua shows not just a change in process but a change in outcome.

Had a White House official not had that “discussion” with acting Secretary Duke, it seems, 5,000 people would now have six more months to prepare their return to Nicaragua (a country that’s since descended into serious civil unrest) or try to make plans to flee elsewhere.

Who made the decisions to end TPS protections, and why?

It’s entirely legal for the White House to influence decisions made by the Department of Homeland Security.

But there’s a difference between influence and control. When it comes to TPS, federal law is clear: The decision about whether a country gets TPS, or whether a country that has it gets an extension, belongs to the homeland security secretary, not the president.

A DHS official in a former Democratic administration (not authorized to discuss the specifics of past deliberations) told me, “I don’t think I remember the White House ever actually telling us to reverse a decision for TPS, or to change the duration” that protected people would have.

Just as importantly, the DHS secretary’s decision about whether to extend or end TPS for a given country is supposed to be based on conditions in that country. If she finds that the conditions for TPS designation persist, she’s supposed to extend it; if they haven’t, she’s supposed to end it and provide for an orderly return.

Under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, TPS generally got extended — the Nicaraguans currently protected by TPS have been living in the US since 1999, when they were first granted protection in the wake of Hurricane Mitch. Under President Trump, it’s most often been canceled.

Ostensibly, the change is due to a difference in legal interpretation. The Trump administration says its job is to review whether the country is still suffering from the aftermath of the original disaster that caused it to qualify for TPS to begin with — which is harder to argue when the original disaster happened 20 years ago, as in Nicaragua.

“TPS was always meant to be a temporary mechanism to address urgent humanitarian conditions,” DHS spokesperson Katie Waldman says. “After a thorough review, DHS determined some countries no longer met the statutory requirements to justify extension of TPS, and thus, pursuant to law, DHS was required to terminate TPS status.”

The lawsuit challenges the Trump administration’s ability to simply reinterpret a statute and overhaul policy to meet it.

But just as importantly, it charges that the legal interpretation is a fig leaf — that the Trump administration is killing TPS because it has a broader agenda of restricting immigration into the United States.

The documents uncovered — which provide the most extensive glimpse into decision-making on immigration within Trump’s DHS that the public has seen so far — raise questions about whether Duke, Kelly, and Nielsen had accurate information about conditions in the countries they decided to send people back to.

Emails between officials at US Citizenship and Immigration Services show political appointees pushing career staffers to include more positive facts about life in Haiti, for example, so that there was more to the report than “Haiti is really poor.” (During a different iteration of this fight, a career staffer countered that “It IS bad there … the conditions are what they are.”)

The plans to strip protections from immigrants are intended to pressure Congress to pass an immigration bill

The exchanges involving Bossert, meanwhile, raise questions about what other factors were being considered.

A few days before the November 2017 deadline for Nicaragua, Duke had gone to a meeting at the White House convened by the National Security Council. A “discussion paper” provided for the meeting recommended that DHS end TPS not only for Nicaragua but for Honduras, El Salvador, and Haiti as well. (Haiti’s deadline was two weeks later than Nicaragua’s, and El Salvador’s wasn’t until January.) And all four countries’ protections would be set to expire on the same day.

The purpose of this, the discussion paper said, was to increase pressure on Congress to take up immigration bills Trump wanted — namely, reducing family-based immigration and the visa lottery in favor of “merit-based” immigration.

“Terminate with an effective date of January 5, 2019 and engage Congress to pass a comprehensive immigration reform to include a merit based entry system,” the discussion paper recommended. “A 12 month delay in the effective termination date would allow for an orderly transition period for beneficiaries. Moreover, it would allow Congress time to act and to factor the fate of TPS beneficiaries into legislation.”

(The discussion paper recommended that the White House could signal its support for such a bill; in January, President Trump would kill a budding immigration compromise because he didn’t want to allow people from Haiti and other “shithole countries” to stay in the US.)

Duke, who left the administration this April, didn’t follow that recommendation for the three countries with the most TPS holders in the US: Haiti, El Salvador, and Honduras. Indeed, her decision to punt on Honduras for six months reportedly angered Kelly and Bossert.

But when it came to Nicaragua, she did follow the White House’s timeline.

She did so despite an official recommendation from the State Department to give Nicaragua “an 18-month wind-down period (that) would provide adequate time for long-term beneficiaries to arrange for their departure.” And she did it at the last minute, thanks to “new information” about a “strategy” from Bossert, Trump’s homeland security adviser.

In the months since that decision was made, the situation in Nicaragua has deteriorated drastically, as civil unrest has killed hundreds. Recent reports indicate that 200 Nicaraguans a day are fleeing the country for neighboring Costa Rica.

One of the pieces of evidence for Nicaragua’s recovery cited in the regulation ending TPS (published in January) was that there was no active State Department travel warning for the country. There is one now. It was published July 7, 2018 — the day after the US evacuated all non-emergency diplomatic personnel.

That’s the country to which, as it stands right now, more than 5,000 people will be expected to return in the next four months or so.

As it stands — unless the administration flip-flops and redesignates Nicaragua for TPS based on the current unrest — the best chance for the 5,000 Nicaraguans is for the judge overseeing this lawsuit to come to the same conclusion that judges have with Trump immigration policies from the first travel ban to the cancellation of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program: that it’s illegal because of how the decision was made.

Sourse: vox.com