England qualify for quarter-finals after beating Slovakia 2-1 in extra-time; Three Lions face Switzerland on Saturday; Jude Bellingham scored leveller 86 seconds from time before Harry Kane scored winner one minute into extra-time

England have booked a date with Switzerland in the quarter-finals after a woeful performance against Slovakia – so what problems does Gareth Southgate need to address?

England were 86 seconds away from crashing out of Euro 2024, a result that arguably would have defined Southgate’s reign and ended his eight-year tenure on a tragic low.

However, Jude Bellingham’s late leveller and Harry Kane’s winner one minute into the first half of extra-time secured an unlikely ticket into the quarter-finals.

Here, we investigate six glaring issues Southgate must fix before his side face the Swiss on Saturday.

- England 2-1 Slovakia (AET) – Match report

- How teams lined up | Match stats

- Euro 2024 schedule: Last-16 ties

- Download the Sky Sports App | Get Sky Sports on WhatsApp

1 – Sharpen the attack

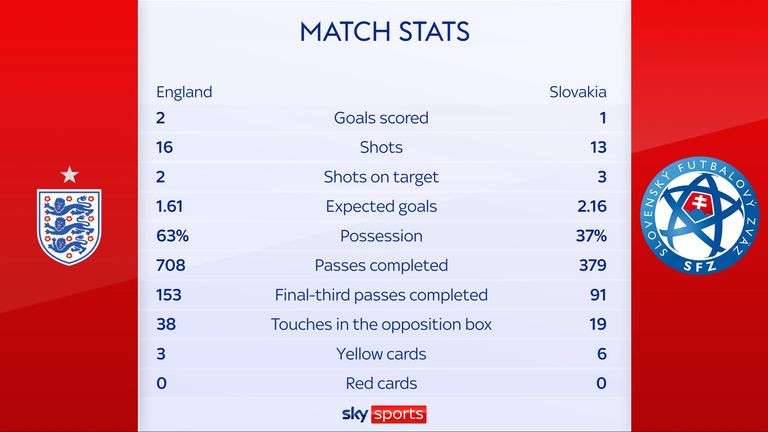

The Three Lions mustered only two shots on target in 120 minutes and scored from both of those attempts.

Slovakia managed three shots on target during the game and registered 2.15 expected goals – more than England’s 1.52 xG.

Datawrapper This content is provided by Datawrapper, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Datawrapper cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Datawrapper cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Datawrapper cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

The xG race chart below reveals how close England came to losing their lead in extra time when Peter Pekarik blazed over from the six-yard box with an xG of 0.63, although his effort might have been called offside had it gone to review.

England have struggled to create chances at the tournament. Among the remaining teams, only Slovenia have registered fewer shots and xG per 90 minutes.

Datawrapper This content is provided by Datawrapper, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Datawrapper cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Datawrapper cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Datawrapper cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

2 – Pointless possession

England have averaged 59.7 per cent possession across their four games – only Portugal and Germany have averaged more among all 24 teams.

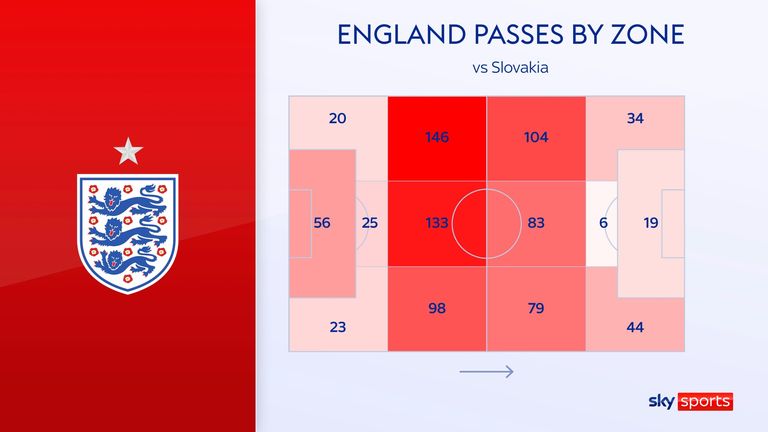

Southgate’s side surpassed their tournament average against Slovakia with a 63 per cent share of the ball. However, the majority of that possession was in their own half – with centre-backs Marc Guehi and John Stones exchanging 64 passes alone.

The graphic below shows England have registered far more passes in their own half than any other side, reflecting how they are clearly struggling to advance upfield on the ball.

Datawrapper This content is provided by Datawrapper, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Datawrapper cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Datawrapper cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Datawrapper cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

The graphic below shows the passing directions of all England players who primarily held each position against Slovakia – revealing a team-wide tendency to pass sideways and backwards.

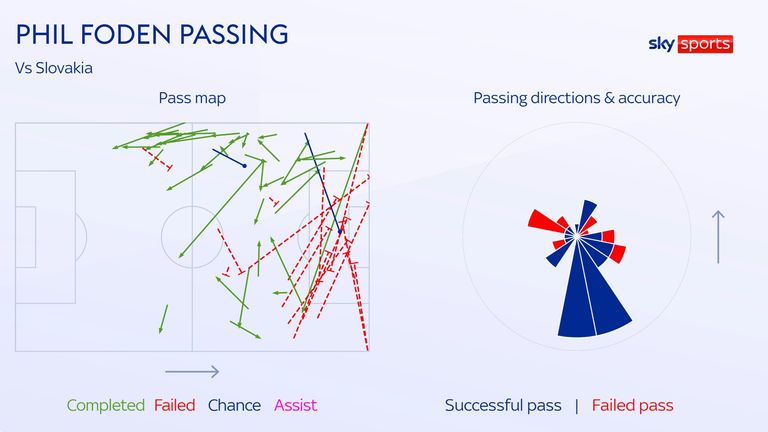

Phil Foden stands out most for passing backwards and struggling to find team-mates with his crossfield balls from the righthand channel.

Foden fact

Phil Foden has made 77 backward passes at Euro 2024 – only Germany’s Joshua Kimmich has made more (83). However, that characteristic is part of Foden’s game: the forward made a chart-topping 549 in the Premier League last season.

Indeed, Foden only has a 17 per cent success rate from crosses at Euro 2024 – a below-average rate among England players. It’s worth noting that many of those crosses have come from corners.

Datawrapper This content is provided by Datawrapper, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Datawrapper cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Datawrapper cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Datawrapper cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

3 – Sitting too deep with ineffective press

England appear to be sitting too deep… and the numbers suggest they certainly are.

The metric ‘starting distance’ measures how far upfield teams typically start passing sequences. It reflects where on the pitch a team regains possession.

England’s average starting distance at Euro 2024 is 42.4m, which would have ranked seventh in the Premier League last term – just edging Bournemouth’s 42m.

For context, Manchester City typically started their sequences 46.4m upfield last season.

Datawrapper This content is provided by Datawrapper, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Datawrapper cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Datawrapper cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Datawrapper cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

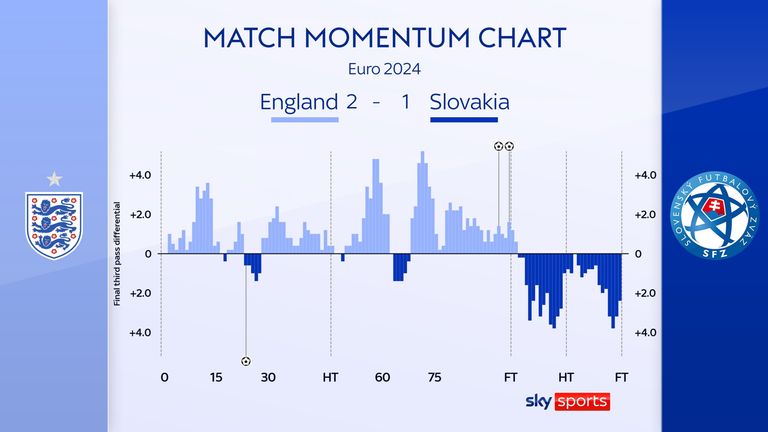

Another criticism waged at England this summer has been their tendency to drop even deeper after taking the lead.

The graphic below shows how Southgate’s side have been on the front foot when trailing in games, but on the back foot to protect leads when holding a one-goal advantage.

To compound England’s troubles venturing into opposition territory, the Three Lions also have the third-worst press among the remaining teams.

The graphic below ranks the number of passes a team allows an opposition side to make before making a defensive action – frequently called ‘PPDA’.

Datawrapper This content is provided by Datawrapper, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Datawrapper cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Datawrapper cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Datawrapper cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

England have typically allowed opponents to make 16.1 passes before attempting to intervene – only Slovenia and Romania have been less intense.

Starting distance and PPDA often correlate, with teams playing high lines usually deploying an intense press.

As a result, Spain, Portugal and Austria have played higher than any other side among the active teams and those teams also have the most intense presses.

Image: England have a tendency to sit back after taking a lead

4 – Get Kane on the ball

Harry Kane has two goals to his name but has often looked isolated up top and struggled to hold up play.

Indeed, the striker has averaged nearly half as many touches as any other England player with just 27 per 90 minutes – including goalkeeper Jordan Pickford.

Datawrapper This content is provided by Datawrapper, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Datawrapper cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Datawrapper cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Datawrapper cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

Of course, strikers often have fewer touches. Erling Haaland is a classic example.

However, most England fans have become accustomed to Kane dropping deeper at times to influence the game, which he has struggled to achieve so far in Germany.

Kane fact

Only Slovenia’s Andraz Sporar has averaged fewer touches per 90 minutes than Harry Kane among the teams remaining at Euro 2024 – factoring in players that have registered 90 minutes or more of action.

Which team-mates bring Kane into the game most? There is growing clamour for Southgate to start Cole Palmer and that could benefit Kane, with the two players projected to exchange more than six passes per 90 minutes – having only clocked 58 minutes on the pitch together so far.

Trent Alexander-Arnold also ranks fourth for passing combinations with Kane – ahead of Kyle Walker and Kieran Trippier.

Datawrapper This content is provided by Datawrapper, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Datawrapper cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Datawrapper cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Datawrapper cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

Kane has lost possession uncharacteristically five times during the tournament, struggling to maintain possession in tight spaces – but the Bayern striker has not been England’s worst culprit.

In fact, England’s other three regular starters along the front line have all had more unsuccessful touches: Phil Foden (seven), Bukayo Saka and Jude Bellingham (both six).

5 – Stones struggling, Guehi suspended

John Stones has also appeared slightly rusty in Germany, having played every minute of every game so far. He will have a new centre-back partner against Switzerland, with Marc Guehi suspended after picking up another booking.

The centre-back went to sleep when a free-kick was passed to him by Bellingham in the second half presented an open goal for Slovakia – fortunately for Stones and England, David Strelec failed to find the target from the halfway line.

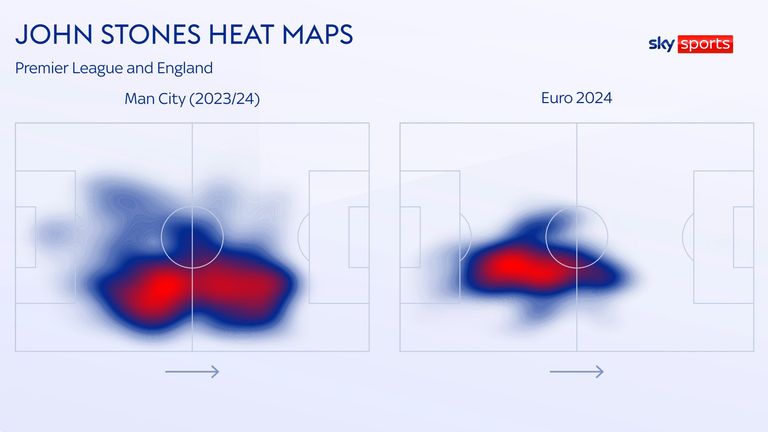

The graphic below shows how Stones has notable passing variation at Manchester City – but passed sideways almost exclusively at Euro 2024.

Additionally, England have been accused of being too static in possession.

The heat maps below underline how Stones’ lauded forays into midfield have benefited Pep Guardiola’s champions – working in both halves equally. However, Stones has operated almost entirely in his own half at Euro 2024.

- Gareth Southgate: I never felt this would be the end of our Euros

- Ratings: Jude Bellingham the poster boy of Euro 2024 redemption

6 – Left-back conundrum

After Southgate’s reserved approach at the tournament, eyebrows were raised when he moved Saka into a left-back role after Kieran Trippier was forced off with a calf injury.

However, the left-back position has troubled England throughout the tournament – with no fit, natural left-footed player to occupy the position. Walker has also had a stint in the role.

Among the regular England starters, Trippier has received the second-lowest average player rating (5.0) from our readers at Euro 2024 – only Kane has a worse score (4.8).

Datawrapper This content is provided by Datawrapper, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Datawrapper cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Datawrapper cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Datawrapper cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

There are question marks about whether Luke Shaw should earn a starting berth if declared fit – having last played competitive football in February.

In terms of playing players in their customary position, Joe Gomez would be the obvious choice to replace Trippier against Switzerland – if the Newcastle full-back is ruled out.

Only Shaw has more experience than Gomez at left-back among the current England squad. In fact, even Saka has more experience than Trippier and Walker, having also played right wing-back during extra-time against Slovakia.

Datawrapper This content is provided by Datawrapper, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Datawrapper cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Datawrapper cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Datawrapper cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

Hang on… England are still favourites?

Despite all of the above… England’s chances of winning Euro 2024 naturally increased after their below-par win against Slovakia which saw them reach the quarter-finals – having leapfrogged Germany and France in recent days as tournament favourites.

According to the latest Opta data, the Three Lions now have a 50/50 chance of reaching Berlin on July 14 and a 24 per cent chance of going all the way.

Datawrapper This content is provided by Datawrapper, which may be using cookies and other technologies. To show you this content, we need your permission to use cookies. You can use the buttons below to amend your preferences to enable Datawrapper cookies or to allow those cookies just once. You can change your settings at any time via the Privacy Options. Unfortunately we have been unable to verify if you have consented to Datawrapper cookies. To view this content you can use the button below to allow Datawrapper cookies for this session only. Enable Cookies Allow Cookies Once

Why? England’s easier side of the draw plays a part, dodging a heavyweight-laden route to the final that includes hosts Germany, France, Spain, Portugal and Belgium.

So, Southgate has numerous problems to address but he can utilise five full days to take stock and reflect on his side’s underwhelming performances to date – aware of the nation’s expectations from a side still tipped to go all the way.

Sourse: skysports.com