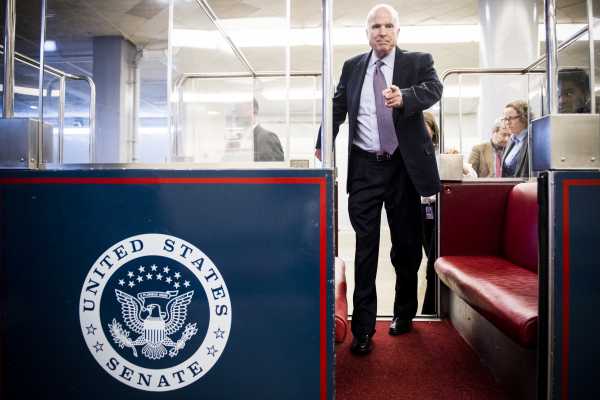

Soon after the announcement of Sen. John McCain’s death, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer came out with a striking suggestion to rename the Russell Senate Office Building after the late Arizona senator.

It would be a dramatic step, to be sure. There aren’t many congressional office buildings around, and a lot of noteworthy senators from American history lack formal commemoration. But it also seems like an elegant solution to the somewhat embarrassing reality that even though former Sen. Richard Russell (D-GA) was an iconic figure in his day, he was also an arch-segregationist and the key legislative leader of the white supremacist movement in America during its final two decades of formal high-level political authority.

Simply swapping out Russell for a more conventional liberal Democrat (Ted Kennedy, say) would be a hard sell in a polarized environment. But why not swap out a Democrat whom contemporary Democrats don’t like for a Republican who is broadly respected on both sides of the aisle? The fact that honoring McCain serves as a sub rosa way of slamming President Donald Trump — and the fact that Trump is clearly annoyed by the impulse to honor McCain — only makes it all the better.

But of course, for Republicans, that’s precisely the problem. McCain, though a fairly reliable GOP vote, certainly annoyed his fellow Republicans plenty of times over the years by being less reliable than your average Senate Republican. And while few in the caucus share Trump’s level of distaste for the man, almost none of them want to openly cross Trump.

Consequently, we are now witnessing the odd spectacle of Republican senators trying to stop a Democratic plan to swap out a white supremacist Democrat in favor of a war hero Republican. Relative to most political controversies, the stakes here are genuinely minimal. But as a symbol of the sweeping changes in American politics over the decades — and the ways the racial realignment of the 1960s continues to roil the political landscape — it’s hard to think of anything more perfect.

Who was Richard Russell?

Richard Russell got his start in politics early, winning election to the Georgia state legislature at 24, becoming speaker of the Georgia House of Representatives soon after, and becoming governor of the state at age 33 in 1930.

Russell was a progressive in the context of Georgia politics at the time, and when Sen. William Harris died in 1932, Russell won a special election to fill the remaining years in his term as a New Dealer. His successor as governor of Georgia, Eugene Talmadge, was from the more conservative faction of the Georgia Democratic Party and challenged Russell for renomination in 1936.

Russell beat him handily, positioning himself as a pro-Roosevelt, pro-New Deal legislator. But after the 1938 midterms, in which liberals generally fared poorly, Russell aligned himself clearly with the so-called Conservative Coalition, an unofficial alignment of mostly Midwestern Republicans and mostly Southern Democrats who held the majority in Congress and acted to ensure that though the New Deal would not be rolled back, there would also be no further expansion of the welfare state.

Intraparty ideological tensions were swiftly muted by the growing storm of World War II, since Roosevelt, though a liberal on domestic issues, was hawkish on foreign affairs and so were conservative Southern Democrats. Russell championed the war and agricultural interests, and in 1946 bridged some of the gap inside the party by authoring the National School Lunch Act, an important anti-poverty measure that also served as a subsidy to farmers.

As chair of the Senate Armed Services Committee, he headed the investigation into Harry Truman’s decision to fire Gen. Douglas MacArthur. Russell was generally seen as having successfully smoothed over a difficult situation. He was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1952, but even though he was an influential senator, it was simply no longer acceptable in national Democratic Party politics to be a staunch segregationist like he was.

He became instead a mentor to Lyndon Johnson, who ended up breaking with Russell on civil rights first in a small way over the weak Civil Rights Act of 1957 and later and more dramatically over the strong Civil Rights Act of 1964. But despite their differences on this, Russell continued to be a close Johnson ally on some domestic issues and especially on the war in Vietnam. The war eventually alienated Johnson from the liberals he had aligned with on racial issues. Russell won reelection in 1966 and died of emphysema in 1971, thus passing from the scene before the tides of racial realignment swept down ballot in the 1970s and ’80s.

A year after his death, the Beaux Arts Senate office building on Constitution Avenue was named after him.

How did Russell get an office building named after him?

Construction began on what was to become the Russell Building in 1903, and it opened six years later.

Throughout the 19th century, both the House and Senate had continuously added new members, and the Capitol Building consequently became overcrowded. Both the Russell Building and what is now the Cannon House Office Building were commissioned to provide the additional space. The structure expanded in 1933 and did not yet have a name at the time of Russell’s death.

The former senator was, importantly, seen at the time as a moderate on racial issues for a white Southerner. He didn’t endorse Strom Thurmond in 1948, he didn’t defend lynchings or Ku Klux Klan terrorism, and he didn’t engage in the kind of over-the-top demagogic rhetoric associated with Southern senators like Theodore Bilbo or “Cotton” Ed Smith. Thus, at the time of his death, he was seen primarily as a long-serving and influential moderate senator who’d been at the center of a lot of important political events.

The 1970s were also a time when both parties saw the South as a key swing area (in 1976, Jimmy Carter would win the White House by carrying all the old Confederate states while losing Illinois, California, and Vermont), and Russell was the leading Southern legislative figure of the mid-20th century.

The political tradition to which Russell belonged — supportive of most of the New Deal and some of the Great Society but critical of civil rights — died out rather swiftly after his death. Modern-day Southern Democrats like Sen. Doug Jones (D-AL) rely heavily on African-American voters, while modern-day Southern Republicans are more consistently right-wing on economics. Consequently, there’s no particularly vociferous pro-Russell constituency out there.

(McCain himself once opposed the creation of making Martin Luther King Jr. Day a federal holiday, but he later recanted on this subject, saying in 2008, “We can be slow as well to give greatness its due, a mistake I myself made long ago when I voted against a federal holiday in memory of Dr. King. I was wrong.”)

Then again, that’s not necessarily so surprising — several congressional office buildings are named after profoundly obscure figures like Philip Hart or Nicholas Longworth, who are best known these days for having buildings named after him.

So what’s the problem with the renaming?

Here’s where things get a little weird. The epicenter of opposition to the name switch seems to come from the Georgia Republican Party, and in particular Sen. David Perdue, who thinks it’s unfair to un-memorialize a former Georgia senator over what he calls “one issue.”

What’s odd, though, is that while Perdue does not defend Russell’s defense of segregation, he also doesn’t defend Russell’s role in expanding the welfare state. He’s just anti-anti-segregation:

In short, Perdue doesn’t like Russell’s record on economics, and he doesn’t like his record on race either. But he more fundamentally doesn’t like the idea of penalizing Russell for his record on race.

That sounds odd, in part because it kind of is odd, but if you think about the broader context of contemporary politics, it kind of makes sense. Southern Republicans have, after all, repositioned the party of Lincoln to be the party of defending Confederate memorials against “politically correct” Democrats who want to take them down. The pro-memorial stance requires a politics of anti-anti-racism that essentially requires them to stand by Russell.

Separately, but complementarily, it’s obvious that Trump didn’t like McCain, doesn’t like the idea of honoring McCain, and would be annoyed by any Republicans who stepped up aggressively in favor of a pro-McCain stance. Consequently, the majority of the GOP caucus is left standing around in a somewhat paralyzed state as the party finds itself taking the side of a long-dead Democratic segregationist over a popular, recently deceased member of their own party.

This seems unlikely to be a major voting consideration for anyone in November, but as far as these things go, it has to be seen as a solid tactical win for Schumer and the Democrats.

Sourse: vox.com