Degenerates need examples, too.

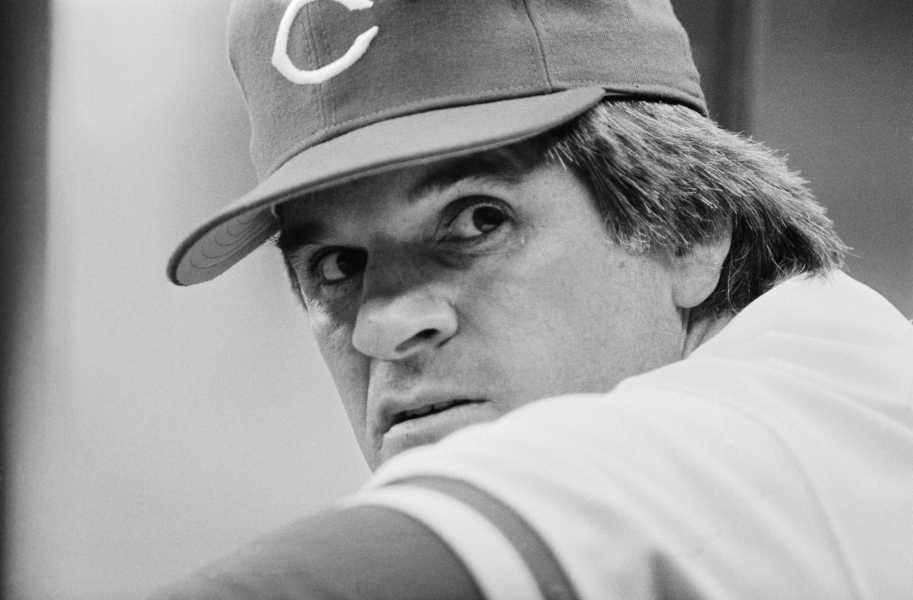

The story of Pete Rose is the story of America. It’s my story. It’s our story. A life failed, in the richest and most spectacular fashion. A miserable, downtrodden, hopeless romance with the juice. A desperate desire to fix. And the supreme knowledge that any day—and for Pete it was Monday—life comes falling down no matter how well we play our cards.

And so I couldn’t help but feel a sweet pang of sadness and twisted fate when, leaving the Megalopolis screening on a rainy, cold September night, I read Pete had died. In that moment, whatever triumphs he manufactured on the diamond didn’t matter much to me. As a 37-year-old, I never really knew Pete the player. But I knew Pete the gambler.

I know the smell of a casino floor at 7 AM, when beleaguered baccarat players are scooping up their winnings as cold-blooded, red-eyed monsters gear up for a day at the horse track. When I worked for Citizen Free Press, I had too much money and too much time and too much anger to know what to do with. I’d throw whatever I could at the ponies, or the wheel, or the gridiron. Anything, really. Didn’t matter. The Buffalo Thunder Casino and Sportsbook was a slumlord’s paradise—where riches went to die, and for three long, arduous years it was my pain palace.

I knew each bookie by name. Paula, Ben, Julio. Paula was my favorite.

March Madness was always the toughest month for me, with games running 13 hours straight for an entire week. On those days, I was one of the first through the Thunder’s door. Paula offered coffee or a stale croissant—the perks of being a degenerate—and asked which channel I wanted the big screen on. Looking for an edge one morning, I asked Paula who the best handicapper was in the joint and she pointed to the corner.

There sat John—a tall, bronze man of Aztec descent who would’ve made a fine warrior centuries before. Smoking was prohibited in the casino but every time I looked in John’s direction, I spotted phantom smoke curls, whipping and jumping off his bald head. Maybe it was just the steam rolling off his brain. Maybe it was the same pain I felt, showing itself in ways unknown. Whatever it was, John was cooking.

John would sit there from sun up to sun down with a long sheet of games in front of him. Depending on the time of day, men would huddle around John and ask for his take on a litany of games. He loved to give advice. John knew baseball, he knew basketball, he knew football. Hell, John knew soccer and the horses too. More than anything, John knew himself: a gambler.

Early one morning, when no one was around, I stood up, walked to the corner, and pushed out my hand—“I hear you’re the best sports bettor in this wormhole.” A big, bellicose laugh rang from his innards. “Who told you that?” I pointed to Paula. “She just takes my money.” He laughed again. This time, so did I. John told me to take a seat. He wanted to know: Who did I like?

“Duquesne ML,” I replied. I had just watched the Dukes rip the living, beating soul from my VCU Rams in the A-10 Final and the underdogs looked primed to make some noise in March. John laughed again. It wasn’t in his nature to bet underdogs. He liked betting favorites and he liked to bet them big. “Who do you got?” I asked. “South Carolina women. Spread. -35.5.” He cackled. I could see the steam rising from underneath his ballcap.

There are many ways to bet on sports. The moneyline (or ML) is the simplest to understand. You pick a team and if that team wins, you win. But sometimes a team is favored to win or lose by so many points that the ML is not a worthwhile bet and that’s where the spread comes into play. So, when John told me he was betting “South Carolina women’s spread by -35.5” what he was telling me was that he expected a rout. A 36-point rout to be exact.

I marveled at his confidence. “Thirty-six points?” I asked incredulously.

“The girls are different, man. They’re mean. They don’t stop. They’ll keep grinding and win by 40. Watch.” I didn’t lay the bet but I took a seat near him that allowed me to monitor the South Carolina game. Sure enough, the Gamecocks fired on all cylinders and they didn’t let up either. They beat Presbyterian by more than 50 points. John was right.

After that day, John always looked for me when I came barreling through the door. I learned that he had been a baseball coach at a high school in Santa Fe for a couple decades and, nearing the end of his career, guided the best prospect he ever coached to a full scholarship at the University of Oklahoma. “The kid washed out,” he told me in a disappointed growl.

And so it was that John had become an addict. First through love, and then through pain. And didn’t I know that feeling myself? Isn’t that why I was there? The extra point I missed against Hermitage. The team I quit on. I could tell you of all my big wins (and bigger losses), but that’s never what it was about. It was about glory days. Gone. Out there somewhere, floating in the time and space that turns forever.

The morning after Pete died, my editor sent me a thread about the late Reds’ gambling career.

A young man, not unlike myself, hit Harrah’s sportsbook far too early one morning and noticed a sunken figure in the corner. After a couple hours of betting thoroughbreds and harness racing to themselves, the two men struck up the kind of bizarre friendship I’ve come to know too well—awkward, brief, and all-knowing. Brothers from another dimension.

The man in the corner was, of course, Pete Rose. “DO NOT say anything to him or ask him for anything. He hates that,” instructed the bookie when Mr. Prewitt asked if his bleary eyes were correct. It must’ve been tough for Rose. A pariah to the game he loved but an anti-hero for the rest of us. “When I was a little kid, we used to see him at the old Latonia,” read one comment. “Met him myself at Mandalay Bay” another.

Rose was not the first, nor will he be the last, man of baseball (or any other sport) to bet on games.

Recently, Major League Baseball has done everything in its power to sweep up a major gambling scandal involving Los Angeles Dodgers superstar Shohei Ohtani’s interpreter Ippei Mizuhara. Mizuhara pleaded guilty to stealing nearly $17 million from Ohtani to cover bad bets. Ohtani, whose English is still poor, said he was “shocked” to learn of the situation, but commentators have questioned how Ohtani couldn’t have known about the infractions.

“Mizuhara has a gambling issue,” explained Tom Ellsworth. “He’s got a friendship that truly developed with Ohtani. Mizuhara said: ‘I asked him if he’d pay off my marker, several million dollars.’ And so apparently, over the course of several weeks, $500,000 at a time, which was the max for a wire transfer, went from Ohtani’s account to a bookmaker… The problem I have with Ohtani’s story—it was multiple transfers over three weeks. Wouldn’t you notice?”

Ohtani is currently at the end of “a season for the ages” according to MLB’s own article published Monday profiling his unbelievable 2024 performance. Whether Ohtani gambled or not (and there’s no evidence he did) is sort of irrelevant. Given Rose’s history, Ohtani shouldn’t have been anywhere near someone that was known to have a gambling issue.

That amount of gambling occurring so close to one of the sport’s top players is unnerving. Yet the media refused to dig into it. Turn on Sportscenter tonight and you won’t find investigative journalists beating down the Ohtani mansion; you’ll find highlights of the Japanese-born stud running the bases and batting for the cycle as the year climaxes in October.

With ESPN advertising its own gambling app in between innings, there’s simply too much money and prestige at stake to rip up the floorboards and reveal the underbelly of our games. The rot has become so corrosive that Baltimore Ravens QB Lamar Jackson addressed the millions of points-obsessed fantasy bettors complaining after a Ravens win in which Jackson barely threw the ball.

“This is a ‘TEAM’ sport,” Jackson wrote on 𝕏. “I’m not out here satisfied when I threw for 300yds but took a L. If I throw for 50 yds and we WIN, that’s wtf matters. Yall stop commenting on our socials about the yds yall fan duel or parlays ain’t hit.”

Subscribe Today Get daily emails in your inbox Email Address:

It’s never been clearer—gambling is destroying bank accounts and the games we love. And it’s changing the way we view athletes.

In the bygone era, casinos were physically isolated and served (mostly) as weekend escapes for thrill seekers. Now, the casino is in the pocket of most Americans except those, ironically, who live in states with large Indian populations that still thrive on brick-and-mortar locations. Games run around the clock for millions of Americans who can bet on an incredible array of sporting events—odds for cricket, table tennis, jai alai, and even chess are only a swipe away. Nothing could be worse for an addict—and we’re minting them daily, by the tens of thousands.

Pete Rose wasn’t perfect. Mizuhara’s not perfect. I’m not perfect. The millions of Americans out there betting every night aren’t perfect. It’s a struggle everyday. For Pete. For Mizuhara. For me. For all of us. Depriving the Hall of one of the great players and personalities to grace the baseball diamond fails to tell the whole story. Of baseball. Of America. Of our people. Rose’s induction should serve as both a reminder and a warning. If there ever was a time to make it so, it is today. Pete to Canton. Send it.

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com