Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Every great movie has its origin not in a story but in an idea. In 1967, David Hoffman, a twenty-five-year-old independent filmmaker in New York at a time when the calling was still a rarity, had an idea that was as original as it was impudent. He was aware of the newfound success of documentaries but irritated by the acclaim being won by the so-called cinéma-vérité school, which, as he recalled in a 2019 video, he took to refer to ones in which filmmakers presume to be invisible observers. (A film that he put in that category was the Maysles brothers’ “Salesman,” in which the directors follow a group of door-to-door Bible salesmen on their rounds.) Hoffman expressly said, “I thought cinéma vérité was a joke.”

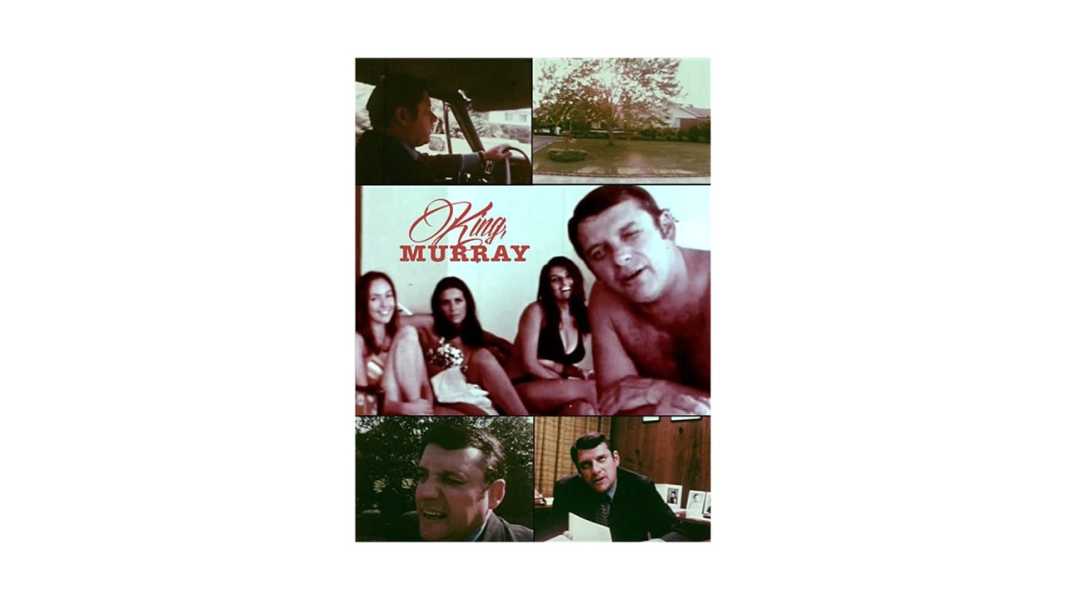

Then fortune smiled, sardonically. An uninvited visitor came to his office one Monday morning—a thirtysomething insurance salesman named Murray King, whose bumptious manner and over-the-top hard sell the filmmaker found “charming.” On the spot, Hoffman invited King to be in a movie; King mentioned that he was going on a junket to Las Vegas that Friday, and Hoffman responded, “I’ll be there with a cameraman and an actress.” An actress? Hoffman’s idea, as he recently described it, was, “Since we’re all creating these scenes anyway, nothing is cinéma vérité, really, then let’s admit it. Let’s see the camera, let’s have some actresses, and let’s call it staged reality.” The junket was at Caesars Palace. King was going with some of the wealthiest clients to whom he’d sold policies, and, according to Hoffman, the hotel was picking up the tab. So King was in his aspirational element: in a palatial suite, with lavish food and drink on the house.

“King, Murray” (its comma cleverly, belatedly dropped into the title card by a shrewd graphic designer) covers three raucous, blustery, exuberant, reckless, self-absorbed days in Murray’s professional life. It starts early in the morning of the day when Murray will take an evening flight to Las Vegas. Hoffman puts his idea into motion from the start, as Murray leaves his house, in a Long Island suburb. Murray (that’s the onscreen figure, contrasted with the offscreen King) emerges from his front door together with the sound recordist, Jonathan Gordon, who’s catching his inexhaustible monologue as it’s just getting warmed up. Hoffman, wielding the camera, films the scene with a choreographic aplomb that Hollywood filmmakers could envy: Murray backs his car out, in a sweeping turn, toward the camera, and is then framed in closeup as he stops to address Hoffman through a rolled-down window, while Gordon, now in the front passenger seat, continues to capture the rodomontade.

Murray, who speaks with a thick New York accent and whose voice is a strident machine-shop whine, boasts to the filmmakers that he has a seventeen-hour work day ahead. He takes them on his daily rounds: visits to clients, a stop at his office, a quick lunch. Each of these encounters is fascinating, appalling, outrageous, and exhausting. Trawling bright suburban streets en route to meetings, Murray speaks (to Gordon’s mike, in the front seat, and to Hoffman’s camera, in the back) of his plans for protecting his clients’ wealth from estate taxes. He quotes at length from Robert Burns’s “To a Mouse,” and after introducing a client to the filmmakers fluffs the client’s ego with a fulsome recitation of his achievements. When another client isn’t home, Murray, hoping that the client’s wife will allow her husband to join him in Las Vegas, flirts with her—playfully, shamelessly—and she flirts right back. In the office, Murray has his secretary pour him a shot of Scotch to get him “calmed down” and proceeds to explain his method, emphatically smacking his desk: “As the day goes, it’s like a rolling stone that picks up moss. I start very slowly, and then towards, this is now, what, it’s a quarter to one? Starts to pick up, pick up, pick up, pick up. The pace gets faster, faster, faster, faster, it’s like running a race—at the end of the race, you have your last sprint.”

Murray’s voice is like an onomatopoeia of energy, as he dashes out of a meeting, hectoring, “Late, late, late, LATE! We’re behind schedule, behind schedule!” In extreme closeup, Murray exults “Mazel tov!” into the phone when a client gets permission from his wife to join the junket; in such moments, Murray’s schmaltzy adolescent exuberance takes its most benign and amiable form. His jovial vigor is more often crudely gendered and sexualized, sometimes physically. After giving a store owner some good news about a medical exam for a policy, he grabs a nineteen-year-old female employee around the waist, jokes about “the way she’s built,” invites her to Las Vegas (an invitation she deftly deflects), and presses a kiss on her. At a snack-bar lunch with two young women, Murray sashays in like royalty, and the relentless gusts of his chatter all but send dishes flying off the counter, as he chats up customers and employees, and importunes a young waitress to come with him to Las Vegas. Her eye roll, out of his view and into the camera, pierces the screen with the recognition of the misogynous essence of Murray’s pestering and raving.

Hoffman knows it and shows it, even explaining, recently, that the film “certainly makes fun of a man who is abusing women, in a way—and all of them were, in a way, and I wanted to stick it to them for that.” In Las Vegas, carousing is the point, and much of Murray’s bluster is centered on sex and women, culminating in a late-night bull session in which he tells a truly ugly story about a man who molested a woman while she was driving, nearly causing an accident. What’s strange about Murray’s abusive manner is that, to all appearances, it’s for show. It’s as if he were playing a Steven Spielberg version of Hugh Hefner, selling a spectacle of uninhibited sexual frolic, and even boasting of his participation, but not exactly admitting to anything and actually doing nothing that’s not, to his mind, playful and innocent, staying out of the scrum that he helps set in motion.

Murray’s sexual mania comes off rather as a boast of vitality, a perpetual athleticism that finds similar, and more immediate, outlet on a tennis court, as when Murray tells his opponent, “I don’t have form, I don’t have a stroke, I don’t have style, but I have a tremendous amount of energy, a bundle of energy, so I’m going to beat you, buddy.” Or when he talks about taking a five-cent bet to run around a swimming pool eighty times; he did it, and got both the nickel and diarrhea. Or when he accepts another bet to swim underwater the length of a pool. He didn’t care about the money: “But when you make up your mind to do it, whether you want to or not . . .”

Strangely, that’s also the attitude Murray candidly takes toward his business. The entire Las Vegas trip is organized around a variety of activities that the filmmaker and his subject concocted: Murray going swimming, Murray getting a massage (an athletic pounding, from a big, boxer-like bruiser named George), Murray showering (chastely and in a bathing suit) with a woman (the actress, bikini-clad), Murray exercising. But the core of the extended sequence is, on the contrary, unexpectedly reflective. Murray’s real interest, the obsessive subject of his attention, is himself. He deploys a spew of fervent self-analyses that, whether uninhibitedly self-deprecating or boastfully obtuse, suggest yet another layer of façades, which he’d rather elaborate on than penetrate. He brags not only that he’s a hard worker (true) but also that he doesn’t really enjoy his work and does it only as a means to an end, to make a good living. He says that he’d never see a psychiatrist—“If I went to a shrink, when he got through with me, I’d be a flop in business”—yet he also knows that the camera itself and, even more, the tape recorder, capturing his voice, play the same role. “I’ll let you in on a secret—I know you’re taping it, I feel like telling you the truth, it’s like a psychiatrist,” he says. And, to this cinematic gatherer of confessions, Murray contrasts the fantasy life of a Vegas trip, with its casinos and its female company—“The blood rushes through his veins, rushes in through his temples, that adrenaline is shooting through his system”—with what this fantasy is an escape from: “A home, a family, a wife, kids, all responsibilities—he left them behind, and he’s in the island of make-believe, shooting the dice in another land.”

“King, Murray” was a success of sorts—in 1969, it played at a New York theatre, garnered a rave review from Vincent Canby, in the Times, played in Critics’ Week at the Cannes Film Festival, was released in France, and received a rave in Le Monde. It’s not clear why Hoffman wasn’t able to follow it up with other similarly recognized movies. (He’s still active as a filmmaker; the real-life Murray King died in 2012, at the age of eighty-eight.) “King, Murray” is now available to stream, on Prime Video, and it needs a restoration—even if the faded print now viewable there marks the film, no less than the attitudes displayed in it, as a decaying historical artifact. Hoffman’s notion of cinéma vérité was inaccurate, and the reality was closer to what he was aiming at himself. The idea, born in France, was of documentaries that revealed their material and practical infrastructure; the early American versions of this, as devised by the producer Robert Drew, involved cinematographers who functioned not as observers but as participants, whether or not they or other crew members appeared onscreen. Still, Hoffman’s demanding and radical view of documentary filmmaking and its inherent contrivances was artistically fruitful, not as a dictate to other filmmakers but a guiding light for his own work. He films distinctively, conveying not only his interventionist presence but also his point of view—avid and skeptical, amazed and repelled.

Hoffman recognized the power of his grafting of fictional situations onto his travels with King. “Yes, I staged scenes, but in those scenes Murray was Murray,” he has said. “He was Murray more than he ever would have been if I had sort of just followed him around.” Above all, Murray is immensely productive at discourse. He’s a world-class yammerer, and there’s something crudely, obtusely majestic about his impulsive, irrepressible, self-revealing, self-denouncing candor: “We just do nothing but talk about it. We’re the biggest liars, bullshit artists in the world.” He’s something like the real-life version of the suburban men in John Cassavetes’s 1970 drama, “Husbands,” in which three upper-middle-class Long Islanders, after the funeral of a close friend, go on a bender and then on a junket of their own making, as if to reanimate themselves with adrenaline and fantasy. Murray is no philosopher, but he, too, lives in the shadow of death, as a seller of life insurance, constantly reminding clients of the menaces that loom and the calamities that threaten. With his bursts of energy, at work and at play, Murray is seizing his own day, perhaps more recklessly, more brutishly, more egotistically, more unfeelingly than most do. But, in the process of exposing his own stunted soul, he lays bare the universal terror. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com