Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

For more than forty years, Stephen Sondheim and George Furth’s musical “Merrily We Roll Along” was a problem in search of a solution. Loosely based on a Kaufman and Hart play of the same name, it opened on Broadway in 1981, in a production that Frank Rich, in the Times, declared “a shambles.” It closed after sixteen performances, but amassed a devoted following (count me among it) as it was continually rewritten and restaged. The show tells the story of three show-biz friends who unite as hopeful youngsters and blast apart in disillusioned middle age: the dashing, talented composer Frank; the neurotic lyricist Charley; and the spunky, lovelorn writer Mary. But the story is told in reverse, starting with the trio’s estrangement and ending with their origin as wide-eyed college kids on a rooftop in 1957, watching Sputnik overhead as they sing about changing the world together.

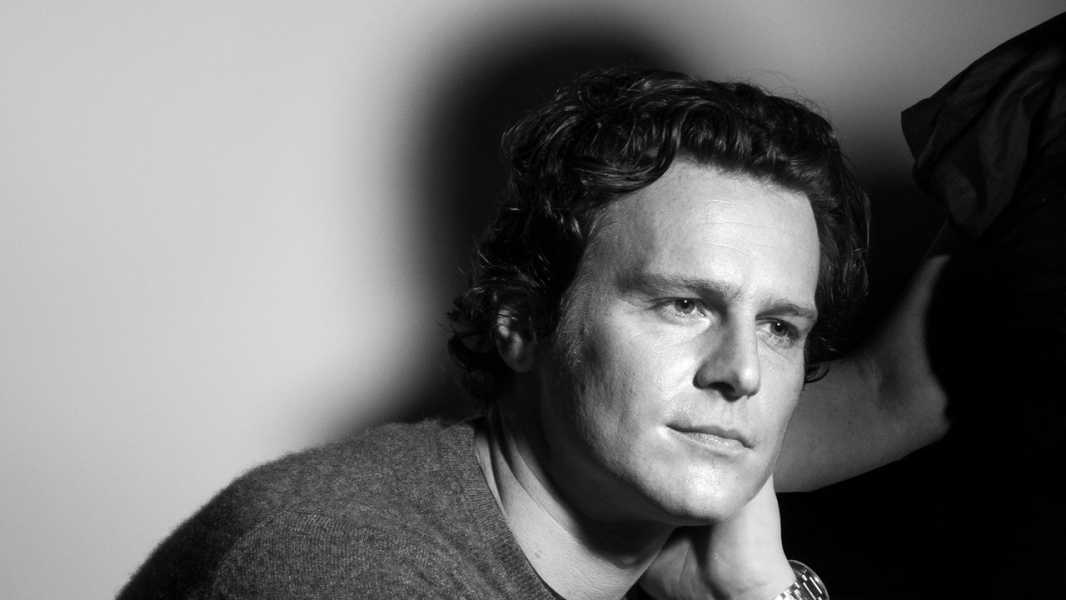

One of the problems with “Merrily” is its protagonist, Franklin Shepard, whom we first meet as a slick, philandering forty-year-old Hollywood producer. It takes two acts to arrive at the charismatic musician he once was, with a lot of mistakes in between. Putting effect before cause gives each scene a painful irony—but how do you get an audience to care about a guy who’s off-putting for so long? “Merrily” is back on Broadway, in a production directed by Maria Friedman, and it’s finally a hit. One big reason is its Frank, played by Jonathan Groff, whose natural warmth shines through even in the character’s older, sleazier incarnation. When this revival opened Off Broadway, in 2022, The New Yorker’s Helen Shaw wrote, “Groff’s silky tenor and angelic face elevate a part that can sometimes be contemptible—for the first time, I could see Frank as both the dreamer who believes in greatness and the glib charmer who believes every lie he tells.”

Groff, thirty-nine, is now nominated for a Tony Award, alongside Friedman and his co-stars Daniel Radcliffe and Lindsay Mendez. He was previously nominated in 2016, for “Hamilton,” in the scene-stealing part of King George III, and in 2007, for the indie-rock musical “Spring Awakening,” as the rebellious schoolboy Melchior Gabor—his breakout role, opposite Lea Michele. Groff had come to New York three years earlier, as a stagestruck, closeted nineteen-year-old from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where he grew up among Mennonites and was obsessed with the original cast recording of “Annie Get Your Gun.” “Merrily,” with its themes of aging, idealism, and the vicissitudes of show business, has had Groff thinking about his own path toward stardom. “Doing this show on Broadway at this time, moving to New York twenty years ago, I’ve now lived the time frame of the show,” he told me recently.

We were talking at a bakery north of Washington Square Park. Groff had glided in on a bicycle. As we spoke, he frequently welled up with tears—he’s a crier—but regained his composure by focussing on a pair of googly eyes affixed to the wall behind me. For our conversation, which has been edited and condensed, I had an experiment in mind.

I want to talk through the past twenty years of your life, but, in the spirit of “Merrily We Roll Along,” do it in reverse chronological order, starting in the present and arriving at the moment when you came to New York.

Sure! I love this.

Let’s start with the extremely recent past. Three days ago, you went to the Met Gala. How was your night?

The big headline for me was Lea Michele was pregnant, and I sat next to her at the table, holding her giant train thing while she peed. She took it off, and I was holding that and her purse. I saw Zac Posen, who was at our table, help Kim Kardashian up the little tiny stairs, and I said to him, “Wow, that was such a sweet moment of the gay helping the diva.” I was relating to him, like with me and Lea. It’s a zoo of famous people. I was going to go to the after-parties, but my body was just, like, “No.” I hit a wall from the shows and the epicness of the week, with the Tony nominations. So I was home by eleven-forty-five, and in bed by midnight.

The Broadway production of “Merrily” opened last fall. You told Jimmy Fallon that Meryl Streep came to your dressing room, where you have a bar named BARbra, and she took a video of you and sent it to Barbra Streisand. Who else has been there?

The first thing that comes to me is sitting in BARbra in October or November, drinking whiskey with Sutton Foster. I came to New York as a teen-ager and saw her six times in “Thoroughly Modern Millie”—now she’s in BARbra, dropping in for, like, an hour and a half after the show, and it’s so full circle. Who else? Patti LuPone was there—another big one for me. Phoebe Waller-Bridge and Martin McDonagh. Glenn Close sent back a bottle of champagne to be chilled in BARbra, which we drank together.

This show, like every Sondheim show, is very dense. Over the course of three hundred-plus performances, are there certain moments that have suddenly hit you a different way, or that you realize have a double meaning?

Double, triple, quadruple, infinity. I’m still having revelations, which really makes me believe that it’s a true work of art. Maria [Friedman] talks about how, with Sondheim’s writing, he “leaves space,” which is why it’s always new. He always needed to work with a collaborator, and she talked about the actor being an essential collaborator. She said the lyric he wrote in “Sunday in the Park with George”—“Anything you do, / let it come from you, / then it will be new”—is Sondheim’s directive to the actor.

The Tuesday after the Tony nominations, I got to the theatre, screamed with Lindsay [Mendez], screamed with Dan [Radcliffe]. [He chokes up.] Then I was singing “Growing Up”—“So old friends, don’t you see we can have it all?”—which has meant so many different things to me in the run of the show. At yesterday’s matinée, Dan and I were sitting on the roof singing “Our Time”: “Up to us, pal, to show ’em.” We’ve done it a million times. We look at each other, and Dan just fucking loses it crying. He had to look away from me. We talked about it afterward, like, “What the fuck was that?” I don’t know. Something just happened.

When you started the show, in 2022, at New York Theatre Workshop, were there kinks in your performance that you’ve since figured out?

I remember feeling shocked at being disliked for so long in the first half of the first act. It was very clear from the energy of the audience that they loved Mary in the opening scene—immediately, they’re on her side. I’m out here as a gay guy, playing this straight, two-timing Hollywood producer who’s cheating on his wife. I’m already having to feel confident in a way that I don’t in my everyday life, this sort of swagger. And the audience hates me. I remember feeling scared and self-conscious. Maria, in that preview process, really helped with that, because she talked about the value of when it’s real, and you’re not playing ugly just to be ugly. The one line that I really struggled with was “I’m just acting like it all matters so people can’t see how much I hate my life and how much I wish the whole goddam thing was over.” That is a really confronting thing to say.

People might say that this is one of the fundamental flaws of “Merrily We Roll Along”—that you’re confronted with this cynical, smarmy Frank in the first act, and you don’t really understand him until the show’s over. I can imagine going into this not knowing if that’s a solvable problem, because it hadn’t been for decades.

Well, Maria wanted us to find the truth. She really believed that these characters weren’t archetypes, that there’s humanity in the writing from beginning to end. I found it after that first week or two of previews, not being so afraid. The line that made me want to do the show was “I’ve made only one mistake in my life, but I’ve made it over and over and over. That was saying yes when I meant no.” I’ve done that a lot in my life, and there was something that felt like the closeted version of myself. George Furth and Stephen Sondheim—I can only imagine being gay at the time that they were gay. Even though Frank is straight, there’s so much repression that feels very familiar to me.

Except that you felt it at the beginning of your life and not the middle, as Frank does.

Yes and no. I still feel it. I’m still trying every day not to go back. I’m obviously out of the closet, so that’s a huge relief, but I’m always going to be reckoning with the Republican upbringing that I had. I’m always negotiating whatever homophobia I’ve got. It’s all in there, still. What we see as ugliness in the top of the show, to stand and say, “I want to fucking kill myself, I hate my life,” and not overdramatize it but try to find it in the most pure, truthful place—it’s still, every night, a meditation to go there.

Let’s wind back. In 2021, you played Agent Smith in “The Matrix Resurrections.” Any good stories about Keanu Reeves?

Getting to play Agent Smith really unlocked rage inside of me that I didn’t know was there. That’s helped me so much with “Merrily,” particularly in the first act. Learning the kung fu was, like, months of fight training. They called me the Savage, because I was so into it. We were shooting a big fight sequence with Keanu, and, after the first few takes, I remember Lana [Wachowski] at the monitor, like, “Jonathan, come over here. Who is that?” I was, like, “I don’t know.” And she was, like, “And what is that?” I said, “Gay rage?”

I’d never shot a gun before. I shot Keanu and thought I had peed my pants, because I had this hot feeling. You know when you pee yourself and it’s warm? It lasted about ten minutes and then it went away. I sat next to Keanu and said, “Keanu, I just had extreme heat from my groin for, like, ten minutes.” And he was, like, “You opened up your root chakra.”

Back to 2015. You’re in “Hamilton.” Tell me a little bit about being inside the phenomenon.

I was inside of it and outside of it at the same time, because I had replaced Brian d’Arcy James when it was Off Broadway. He left a week after they opened. I said yes to the show without having seen it or knowing what I was doing in it, because Lin-Manuel Miranda had asked me to come in for a couple of months. So I got to watch that unbelievable, once-in-a-generation experience from a bird’s-eye view. Every person from every medium would come and see the show.

Who were some of the people who showed up?

The big one for me was Beyoncé. She came back with Jay-Z. I saw the Renaissance Tour four times. I’m obsessed with Beyoncé. And I was, like, “Hi, Beyoncé. I’m Jonathan.” And she was, like, “Were you the King?” And I said yes. She said, “I’m going to steal your walk.” And then she imitated the way that I had walked onstage as the King. I couldn’t speak. Then she said, “When you exited the stage and you moved your shoulders but not your head, you were your own turntable.” Again, I couldn’t speak. And then she looked me up and down, and she said, “I saw everything.” I fucking died!

You turned thirty that year. How was that?

I remember it vividly. We were at the Public Theatre. There was a fire in the East Village, and the show was cancelled that night. I got a cupcake at the deli around the corner from my apartment, on Sixteenth Street, and ate it by myself. I can be a bit of a loner, so that was a happy birthday for me.

Is it true that if “Looking” hadn’t been cancelled, you would have been unavailable to do “Hamilton”?

Very true. I thought I was just going to go Off Broadway for two months and then do the third season of “Looking.” That was my plan. The show got cancelled while we were Off Broadway. I remember being at the Public Theatre and people bringing me anal douches to sign at the stage door, in sadness over “Looking” being cancelled.

The “Looking” era began in 2014. I keep waiting for the rediscovery of that show, like with “Girls,” just because they were both so divisive at the time.

It was a little bit heartbreaking. I remember making the first season, getting to do—Oh, fuck, now I’m crying. [He stares at the googly eyes.] This face is helping me right now. I had come out of the closet, but I hadn’t truly accepted, I don’t think, my gayness. I hadn’t processed it. Getting the chance to do “Looking” felt like I was suddenly surrounded by gay people, making a show about gay people. I’d had gay friends, but never a group of gay friends. That show was like all our journal entries put together and shaken up and recorded for all of time. It was extremely personal and therapeutic and fun. We made the first season in a kind of delightful bubble.

Then it came out, and it was so extreme, the hate for the show from specifically the gay community—I’ve never been on social media, so I don’t remember what it was. But there were articles about the show being boring. It was too gay. It wasn’t gay enough. It’s like being in middle school and reading a poem that you wrote, and everyone having opinions about it. So it hurt. Getting to do the movie [In 2016, a made-for-TV film served as the series finale] allowed us to all have closure.

But, in 2015, Michael Lombardo was our executive at HBO, and I was crying into my salad at some restaurant in West Hollywood, trying to convince him to keep the show going, right before getting on the plane to come do “Hamilton” Off Broadway.

I loved Raúl Castillo, who played your love interest Richie on the show. I interviewed him around then, and he told me that, since he’s straight, you all had to teach him some of the mechanics of what gay people do.

Oh, yeah! God, I love him so much. I officiated his wedding in July.

Let’s go back to 2013, when “Frozen” came out. You voiced the iceman Kristoff and the reindeer Sven. How did that film change your life?

It’s funny—I remember recording some of “Frozen” in San Francisco. I would be teaching Raúl, like, how to lick my asshole while jerking me off—not teaching him, but sharing the ins and outs of gay intimacy—and then going into the recording studio on a Saturday and being Kristoff and Sven in a Disney movie.

When they showed me “Let It Go” for the first time, I was, like, Oh, my God, this will help millions of people come out of the closet. This is the gayest thing I’ve seen in my life! That was the thing about “Frozen”: I don’t think anyone who worked on it thought it was going to be a juggernaut. It’s so weird to think of this now, but when it came out it felt quite alternative, because there was no villain, really, and the love was between two women. Now there are, like, tissues with Elsa on it.

In the years preceding “Frozen,” you were playing a recurring character on “Glee,” Jesse St. James, but also doing Off Broadway theatre. Coming off the hype of “Spring Awakening,” what choices were you making? Were you figuring out how to be famous? Were there things you were turning down?

The big thing, in retrospect, that changed everything was that I fell in love in 2008 and 2009. With “Spring Awakening,” suddenly I was auditioning for “Captain America,” or maybe it was “Superman,” and the lead in Nicholas Sparks adaptations. And choosing to come out felt like making a choice to not really have a film and television career but to hopefully keep working in the theatre. I always wanted to be in theatre, so that was helpful, too. But I remember, at twenty-three years old, suddenly being considered with all these young, straight actors in auditions and feeling, I’m going to come out of the closet, and I’m making a very specific left turn that’s releasing some ambition of being on film or television.

When “Glee” came around, Ryan Murphy asked me to play Finn, Cory Monteith’s role opposite Lea. He was, like, “I wrote this show for you and Lea.” I had just spent two years in “Spring Awakening” as a singing teen-ager. I wanted to act! I didn’t want to be a singing teen-ager for the next seven years, which was the contract that we had to sign for that show. That was the year I came out of the closet, and that was the year I decided to do three Off Broadway shows. I took my desire into my own hands and started to pave my own way.

Franklin Shepard would have been, like, “Get me ‘Superman’!”

If I had decided to stay closeted at twenty-three, I would have become the Franklin that I’m perhaps tapping into a bit.

Tell me about the moment you chose to come out publicly. You were at the National Equality March, in 2009, and I believe told Broadway.com that you were gay?

A month after I left “Spring Awakening,” I went to Italy by myself. I saw Michelangelo’s David, and I started hysterically crying. My brother came to meet me in Rome, and he was the first person that I came out to. Then I came out to my friends and family, and I broke up with my “roommate,” who was my boyfriend for three and a half years. I did “Hair” in Central Park, but there was no occasion to announce that I had come out. I was just sort of living.

Then I fell in love with Gavin Creel. We were doing this march on Washington. The woman from Broadway.com was interviewing me, and she was, like, “Who do you represent at this march?” And I froze. She saw me get tight and was, like, “Oh, never mind.” I remember looking at Gavin, who was holding a bullhorn, directing people into the march. And I was, like, I fucking love him so much. I’m coming out. I’m at the fucking gay marriage-equality march! I walked back over to her and said, “I’m here because I’m gay. And that’s what I’m sharing with you.” She said, “On the record?” And I said, “Yes, on the record.” I hadn’t planned it. It just happened that way.

Now we’re moving backward to “Spring Awakening.” By the time it moved to Broadway, in 2006, you were the twenty-one-year-old lead of the coolest musical in town. What was your actual life like?

I was so not cool. The show was cool, and the music was cool. I had people dropping me off joints at the theatre. And I remember fully understanding the stark difference between who I was playing onstage and who I was in real life, which was an extreme theatre nerd who wanted to be in the ensemble of “Thoroughly Modern Millie” and never would have imagined playing Melchior. It’s his gravitas. And trying to tap into that side of myself, which was a side I’d never experienced before.

Tell me about your audition.

I went to the open call and knew who Michael Mayer was, because he had directed “Thoroughly Modern Millie.” But it was “Spring Awakening” and I was, like, There’s a beating scene? This is so intense! They called me in for Melchior, then had me sing “Hey Jude” in a falsetto, and Michael was, like, “That was your falsetto?” And I laughed at him sort of making fun of me. Tom Hulce, who was our producer, told me years later that he moved my head shot from the “No” pile into the “Yes” pile because I had laughed at Michael in the audition, and he thought, This kid has the ability to let Michael roll off his back. We should bring him back in the next month or two.

It was, like, ten people up for Melchior. They brought me in first, because they thought they would just see me and cut me. But I had worked so hard on the audition material. I remember calling my dad the night before the final callback and saying to him, “I know I can’t be this character all the way yet, but I—”[He tears up again.] I really got to get my shit together! Why does this keep happening to me?

Because we’ve gone on an emotional journey.

I guess so, in reverse! Fuck me. [Pauses.] I knew that I had it inside, if they would just give me the chance. That’s all I was trying to say, but I guess I can’t stop crying while I’m saying it.

In 2005, you made your Broadway début, as an understudy in “In My Life.” Now, this was the weirdest musical I’ve ever seen. As I recall, there were dancing skeletons in a song about how everyone has a skeleton in their closet, a giant lemon that came from the sky at the end, and a girl on a scooter who turns out to be a ghost. And it was written by the guy who wrote “You Light Up My Life,” who then came to a dark end.

And his son!

Yes, his son killed his girlfriend. What the hell was going on with that show? Did you ever go on?

I went on for the ensemble members. I was so excited! I was in my first Broadway show, at the Music Box Theatre, walking in where it says “Stage Door.” And you couldn’t give away tickets to see the show. People were coming to laugh at the show from the audience.

Like “Springtime for Hitler”?

Exactly. And the cast had to do the show, even though people were laughing at them, which is devastating for the actors. But we formed a little family. It’s the plight of the actor. You’re just out there, like Sally Bowles in “Cabaret.” I was twenty years old, so I was lit.

Had you been waiting tables?

Yeah. The whole year before that, I was at the Chelsea Grill, in Hell’s Kitchen. The day I got to New York—October 21, 2004—I moved to Fifty-first Street and Ninth Avenue, before it was super gay, and I walked down Ninth and got a job waiting tables. A week later, I waited on Tom Viola, who runs the charity Broadway Cares, and became a bucket collector. I’d watch the second act of shows and then collect the money at the end. I went to hundreds of auditions, trying to get my Equity card. That, to me, was “Opening Doors,” from “Merrily”—that moment of sheer will and ambition and ignorance.

We’ve now reached our finale, which is 2004. Can you tell me about the decision to move to New York?

My mom was a gym teacher and my dad is a horse trainer, and they didn’t really understand anything about the performing world. But my dad grew up on a dairy farm, and he was supposed to take over and become a Mennonite preacher, which is what my grandfather was. My dad didn’t like cows—he liked horse racing, so he sort of rebelled and did his own thing. My mom always says that nurse, secretary, or teacher were the options for women in a small town at that time, but her passion was sports, so she ended up being a coach.

So they understood the power of fanning the flame of passion. When I was a kid and into acting, they drove me to play practice. They drove me to community theatre. My senior year of high school, my mom drove me to New York to audition for this bus-and-truck tour of “The Sound of Music.” I got that tour, and deferred my admission to Carnegie Mellon. I made ten thousand dollars after a year on the road, and I learned so much from getting to act every day. I wanted to take my ten thousand and move to New York, and my parents were super supportive: “If you feel like you need to go to college, you can always go to college. But take a gamble and move to the city.” I’d worked at this theatre in Lancaster called the Fulton Opera House, where I’d met this girl who wanted to move to New York, so she became my roommate.

To me, “Merrily We Roll Along” is about how difficult it is to stay in touch with the person you were as adulthood knocks you sideways and forward. When you think about nineteen-year-old Jonathan coming to New York, do you feel like you’re the same person? What’s changed?

[He bursts into tears.] I can’t tell why I cry! When we were about to start rehearsal for “Merrily,” I would listen to “Our Time,” and I couldn’t sing it without crying. And, when I think about that version of myself—I think it’s because that person who brings you here does diminish. Maybe it’s the grief for that person. The whole reason that I’m here now is because of that person, but that person no longer exists.

But that person is still in there, somewhere. That voice is so quiet now, but it’s still driving my choices. You have to make choices. You get older, that pure inspiration dies, but it doesn’t have to go all the way away. I think that’s the whole point of the show, why it goes backward. Maria says that Sondheim put all of his regret into it, so that we could have less regret for ourselves. And perhaps the reason it ends with these people, with these versions of ourselves that we remember when we see it, is that it’s an invitation to remember and honor that person.

Why does that make me cry? Is it grief? Is it joy? I don’t know, but I’m so grateful for that purity and that optimism. The first month that I was here, feeling so lost and confused, I pulled the Bible that my Mennonite grandmother gave me off the bookshelf. She gave me that Bible before I left town. I was alone in the apartment thinking, What the fuck am I doing in New York? Or not even “what the fuck”—I didn’t swear until “Spring Awakening,” and when I would sing “Totally Fucked” I would get beet red. And I remember putting the Bible down and thinking, This is not the answer. This is not making me feel good. And then running to Central Park and standing in front of the Bethesda Fountain. I was nineteen, and I was, like, This feels better—but, like, What? Who am I? What am I doing here? I know I want to act, but I’m so scared. And gay. But it was something—some voice, some passion, some inspiration. Some something brought me here. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com