Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

More than a decade ago, as a baby journalist, I received a fellowship from the Asian American Writers’ Workshop to report on Chinatown, in Manhattan. I was still working as an employment lawyer then, and had become familiar with the neighborhood by representing low-income clients. My co-worker, a housing lawyer, invited me to come learn about one of his cases, in which a group of immigrant tenants were facing eviction from their building on Allen Street. I took my camera—I was dabbling in photography—and followed him out.

One of his clients greeted us at the door and led us up a steep, dimpled staircase. Whatever the apartment’s original shape, it had been divided, then subdivided, using drywall and curtains, into a grid of cubbies. A dozen Chinese immigrants lived there, strangers rendered intimates by their hot, cramped quarters. They were seniors, middle-aged workers, young guys, and children, all sleeping within earshot of one another, sharing a bathroom and a kitchen.

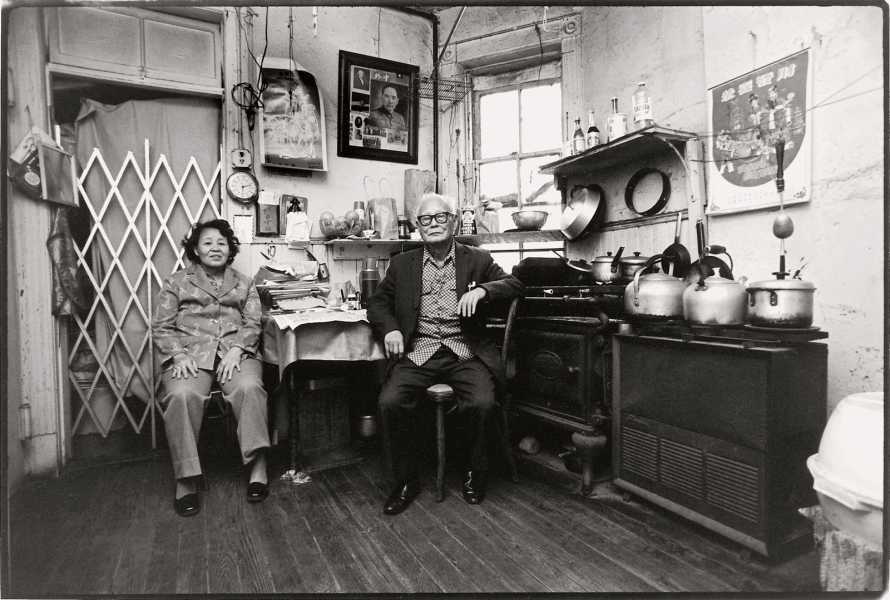

New York, 1981.

New York, 1996.

I took some black-and-white photos, which were published in the Workshop’s online magazine. Later, a tenant organizer asked if we could put the photos on display, at an exhibition space in midtown. I agreed, and prepared a series of large matte prints. On opening night, a tall guy with scruffy hair and glasses came in and began to closely inspect them. It took me a minute to recognize him. He was Corky Lee, the longtime chronicler of Chinatown who described his own photos “as an organizing tool for social change.” I knew him for his interior shots of local tenements (I was essentially mimicking these), documentation of countless protests, and portraits of Yuri Kochiyama and Lily Chin, the mother of Vincent Chin, a Michigan auto worker whose murder, in 1982, became a touchstone in the Asian American movement.

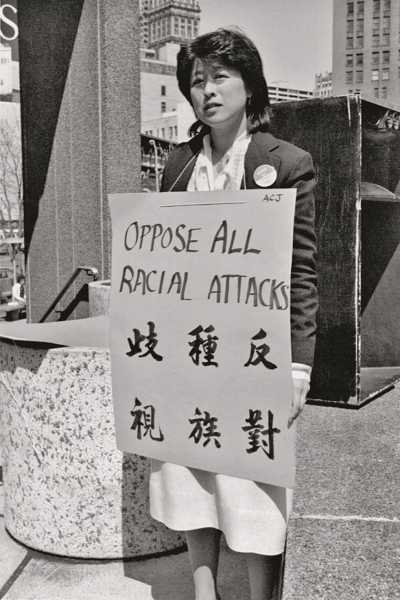

A protest after the killing of Vincent Chin. Detroit, 1983.

Vincent Chin’s mother, Lily. Detroit, 1983.

The author and organizer Helen Zia. Detroit, 1983.

So many people who have spent time in Asian American spaces, especially in New York City, have a story like mine. Lee, who died in 2021, at the age of seventy-three, made a habit of coming to see what was happening in the community. He was omnipresent downtown, like Lou Reed. Many obituaries noted his constancy and devotion, and glossed over his spiky personality. He was there, with his camera and grumpy sense of humor, at every labor strike, every Lunar New Year parade, every court hearing and election that mattered to A.B.C.s (American-born Chinese) like himself and to the larger, shifting mass of Asian Pacific America. He did this mostly unpaid. (For years, he had a day job at a printing company in Brooklyn.) In the documentary “Photographic Justice,” he offers practical advice to students of the craft: “Don’t get hooked on photography unless you’re willing to make tremendous sacrifices in your personal life.”

A new book, “Corky Lee’s Asian America,” edited by the artist Chee Wang Ng and the historian Mae Ngai, collects hundreds of pictures that Lee shot from the early nineteen-seventies to the end of his life. It also includes essays from scholars, family members, writers, artists, friends, and activists. “In endless frames of film,” Renee Tajima-Peña, a filmmaker and a professor at U.C.L.A., writes, “he gave us the gift of our collective memory. Thanks to him, we can still see New York’s Chinatown before the worst ravages of gentrification, and the burgeoning Little India, in Jackson Heights, Queens.” The artist Ai Weiwei, reflecting on a picture taken in New York, after the Tiananmen Square massacre, credits Lee with creating a more personal record: “Without his photo, I would have only a very faint memory of that protest.”

New York, 1974.

Lee felt discontented that his work wasn’t better known; he had tried, unsuccessfully, to self-publish an anthology. He was always in motion, always using the photos to teach or support a campaign, which made it hard to assess their formal, aesthetic qualities—and the story they told about Asian America. Only with this book could I finally see the images in one place, so varied in subject and across time.

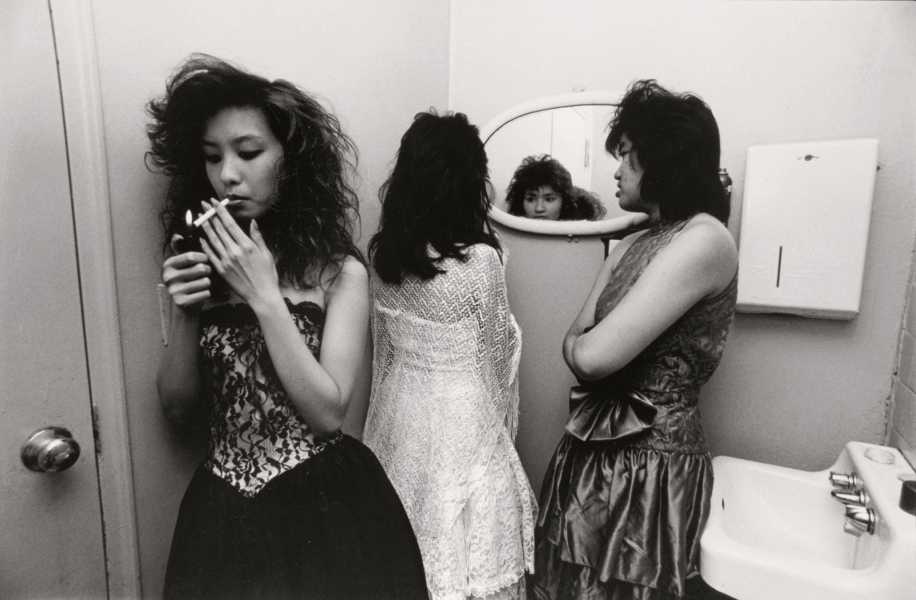

He mostly shot in black-and-white, and horizontal. “I generally use a wide-angle lens and move close, so you get the whole landscape of what I am seeing,” he said. He tended to include people in the frame. How surprising, then, to see in the book an abstract vertical in Kodak Ektachrome: a crosshatch of green, red, and brown fire escapes. Though Lee considered himself a journalist, he wasn’t above stage management. There’s a fun shot, from 1987, of three dolled-up teen-age girls in a bathroom—lace, tulle, big bows, big hair—taking what appears to be an illicit smoke break during a high-school dance. “Although none were smokers, Corky asked them to pose with a cigarette,” the caption reads.

New York, 1987.

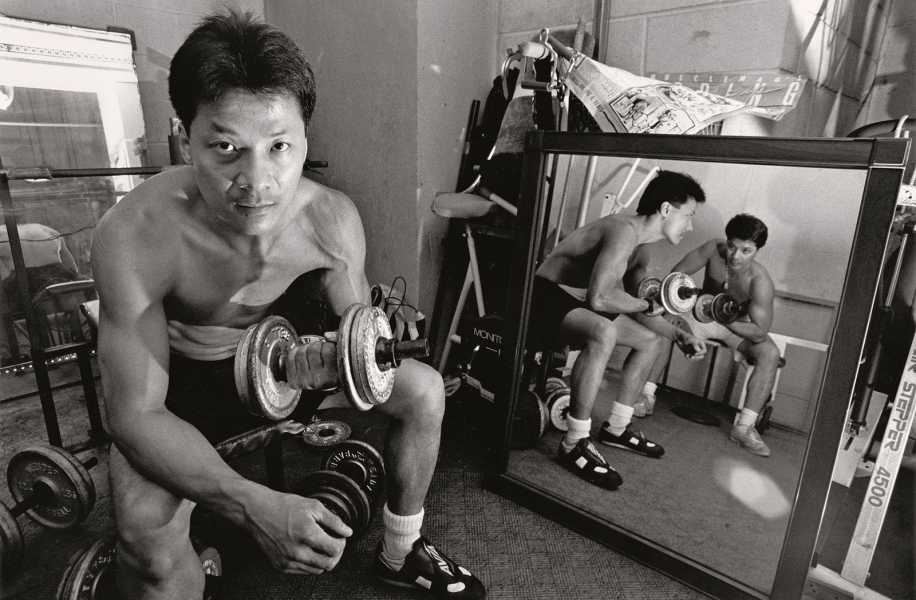

New York, 1996.

When Lee was growing up with his siblings, in an apartment above their parents’ “hand laundry” in Queens, the Asian American movement emerged alongside, and in imitation of, the Black civil-rights movement. To be Asian then was to be East Asian, working class, pro-immigrant, and antiwar: Lee was a student activist and a conscientious objector during Vietnam, though his father had fought with the U.S. during the Second World War.

By the turn of the century, Asians in the U.S. had become too numerous, too diverse, to squeeze into the old set of assumptions. With 9/11, Asian America scrambled both to defend Arabs, Muslims, and South Asians from persecution and to prove their deep-seated patriotism. The images that Lee produced after the attack on the World Trade Center, which was so close to Chinatown, reflect this instability: a turbaned Sikh man wrapped in an American flag, a Chinese American firefighter. Later, Lee joined the American Legion and photographed the descendants of Chinese Americans who had served in the Second World War; eventually, these veterans—an estimated twenty thousand of them, many already deceased—received a Congressional Gold Medal. In 2016, he captured Asian American rallies both for and against Peter Liang, a police officer who was prosecuted for killing Akai Gurley, a Black man in Brooklyn. (Lee himself was a leftist, but, as the editors write in the book, he endeavored to be “ecumenical and took photographs of activities regardless of the organizers’ political persuasion.”)

A candlelight vigil in Central Park, four days after 9/11. New York, 2001.

New York, 2020.

New York, 2020.

Today, Asian Americans still lean Democratic, but they—I mean, we—are becoming more prominent in the Republican Party. It’s common now to see Asians make traditionally right-wing demands, including tough-on-crime laws, landlords’ rights, a ban on affirmative action—rich-people stuff. Our pursuit of social recognition (beyond Hollywood visibility) seems to exploit a feeling of historical grievance, from the Chinese Exclusion Act to recent instances of racially motivated violence. “In 2020 Corky had already documented the ravages of the pandemic on New York’s Chinatown and the upsurge in racism against Asian Americans. But he was gone by the time six Asian women were gunned down at Atlanta spas in March 2021,” the editors, along with one of Lee’s brothers, write in the epilogue. It’s an odd way to wrap up a life. Yes, Lee probably would have travelled to Atlanta, to document this latest Asian American reckoning. But the joy of the book is to get beyond this repetition of mourning and protest—toward some calmer, everyday truth.

A mah-jongg game at the Hong Lok Senior Center. Oakland, 2001.

I love Lee’s photo of a mah-jongg game at the Hong Lok Senior Center, in Oakland, from 2001, in which one player, an elegant old auntie in a cheongsam-style blouse, looks straight at the camera. I love his double portrait of the brothers Arthur and Eddie Ng, from 1996, as they lift weights, shirtless, in what appears to be a janitor’s closet at P.S. 124. Arthur stares at the camera, mid-curl; Eddie’s reflected image, in a mirror, stares at the camera, too. There are personal pictures of great beauty: Lee’s mother, doing needlework in the family’s apartment, next to an ornate shrine to her late husband. Or Lee’s wife, Margaret, in 1999, just before she died, of cancer, posing awkwardly with her own mother at their Chelsea laundry. “I really don’t, in my photographs, show too many celebrities,” Lee once said. “I think ordinary people are probably the most genuine.”

Corky Lee’s wife, Margaret Dea Lee, and her mother, Yun Yee Dea, at the Dea family’s laundry in Chelsea. New York, 1999.

Sourse: newyorker.com