Trump’s favorability has ticked up with many Americans and soared with some traditionally Democratic groups.

Donald Trump speaks during a Buckeye Values PAC rally in Vandalia, Ohio, on March 16, 2024. Kamil Krzaczynski/AFP via Getty Images Christian Paz is a senior politics reporter at Vox, where he covers the Democratic Party. He joined Vox in 2022 after reporting on national and international politics for the Atlantic’s politics, global, and ideas teams, including the role of Latino voters in the 2020 election.

Something confounding is happening in America: Donald Trump, once the least liked presidential officeholder and reviled by nearly two-thirds of the country by the time he left office, is getting more popular.

For the loyal Vox reader, that statement may be hard to believe. Yes, the twice-impeached, multiply indicted former president is still generally disliked: The latest New York Times/Siena poll places his favorability rating at a “weak” 44 percent. But that’s still higher than his Democratic opponent, Joe Biden, who is viewed favorably by just 38 percent of registered voters. As views of Biden have been getting more negative, views of Trump have also been getting more positive.

Across multiple kinds of polling and public opinion surveys, Trump’s favorability appears to have stabilized at a higher place than three years ago. Views of Trump have been modestly improving for most Americans and have actually increased significantly among Black and Latino Americans, younger voters, and working-class people.

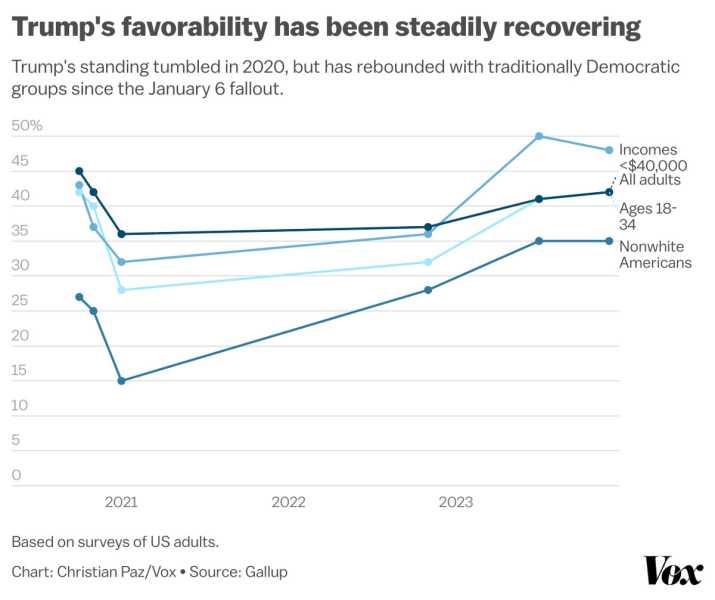

Those shifts are apparent if you dig into the numbers a bit. In Gallup’s surveys of US adults, for example, Trump ended 2023 with his highest favorability ratings since the eve of the 2020 election.

That was true for young adults, aged 18 to 34, where Trump’s popularity plummeted as he tried to overturn the 2020 election but has rebounded since. Forty-two percent of young adults saw him favorably in October 2020, but that dropped to 28 percent in January 2021. His favorability bounced back to 42 percent by December 2023.

The same pattern held among nonwhite Americans, 27 percent of whom saw Trump favorably in October 2020. That plunged to 15 percent in January 2021 but had rebounded back to 28 percent by November 2022. The rebound is even more pronounced among Americans making less than $40,000 a year. Thirty-seven percent saw him favorably in October 2020, while 32 percent said that in January 2021. But that number jumped to 48 percent by December 2023.

Similar trends appear in other polls, as the former Democratic pollster Adam Carlson has tracked for specific subgroups and in general when looking at polling aggregates.

“In the overall trends, Trump’s favorable rating is back to baseline,” Lydia Saad, the director of US social research at Gallup, told Vox. “Among young people, it’s back to where it was before January 6. … It also does not look like he has recovered among white adults, whereas he has improved above baseline among all people of color.”

These data points all suggest that something has changed among the electorate and the country in general, and also that something more pronounced might be happening with younger, nonwhite, and working-class Americans. What could it be? Here are three theories to explain and understand what might be happening.

Explanation 1: Trump is benefiting from economic nostalgia

As the pandemic subsided, the economy became the major storyline of the Biden years. It’s consistently the top issue for all voters, but especially for Black, Latino, and working-class Americans. Trump made the booming pre-pandemic economy central to his reelection pitch four years ago, and he is using it as the central argument against Biden.

Inflation, higher interest rates, and mixed views about the post-Covid recovery continue to be Biden and Democrats’ biggest liabilities. In an inverted way, it also may be one of Trump’s biggest assets in rebuilding his popularity.

In the latest New York Times/Siena poll, for example, Black voters feel as bad about the economy as their white counterparts; Latino voters feel even worse. Similarly, younger voters, under the age of 30, feel worse about the economy than older cohorts. Seventy-three percent of white voters would rate the economy as fair or poor, while 74 percent of Black voters and 84 percent of Latinos would say so. Among young adults, 86 percent would say so, 8 points higher than those 30 to 44 years old.

Among these cohorts of Americans, young people and Latino voters also feel strongly that the economy is worse now than it was right before the pandemic. Seventy-one percent of adults under 30 would say so, higher than the 65 percent of 30- to 44-year-olds, 62 percent of 45- to 64-year-olds, and 63 percent of the oldest voters. Seventy-one percent of Latino voters would say so, compared to 56 percent of Black voters and 66 percent of white voters.

There’s plenty of evidence for this discontent. As my colleague Nicole Narea has explained, Americans think the economy is worse under Biden’s presidency than under Trump’s — despite there being plenty to be optimistic about, regardless of individual perceptions. Economic confidence is lower, concerns about the economy are higher, and Americans are racking up credit card debt, even as they also say they are worried about interest rates on debt.

At the same time, many Americans remember the Trump economy in better terms than they view the current economy. A March CBS News/YouGov poll found that 65 percent of registered voters would rate Trump’s economy as “good” while only 38 percent would say the same for Biden’s economy. And in the latest Times/Siena poll, a similar dynamic emerges. Americans across race, age, and gender feel that Trump’s policies, usually talking about his economic policies, were better for them than Biden’s currently are.

Many of the pandemic’s economic effects in both presidential terms were out of each leader’s control, but that doesn’t change many people’s belief that Biden bears more blame than Trump for the state of the economy.

Explanation 2: Trump is recovering from a remarkably low moment

Elections have consequences, and one of them tends to be that the campaign season divides the country nearly in half. Each side views the other negatively, and the presidential winner is left with the task of uniting the nation, usually with help from the outgoing executive.

Famously, Trump did the opposite in 2020. He was already suffering from low ratings throughout his presidency, but the combined effect of the coronavirus pandemic, the summer of protests and unrest, and his attempts to overturn the results of the election all translated into a steep slide in his approval and his favorability ratings by the time he left office.

The events of January 6 played a major negative role in Trump’s standing, pushing him to such a low standing with the American public that it seems only natural for views of him to have recovered as time marched on and memories faded. In breaking down their survey of adults conducted in the aftermath of the Capitol riot, the Pew Research Center found that Trump’s approval rating had fallen to 29 percent, a 9 percentage-point drop from their August 2020 poll and “the largest change between two Pew Research Center polls since Trump took office.” Much of that shift could be attributed to Republicans turning on Trump in the immediate aftermath of the insurrection.

Somehow, the subgroups who viewed him most negatively found more room to disapprove. From August 2020 to January 2021, Trump’s approval among Hispanic adults sank 11 points; his approval among Black adults fell from 9 percent to 4 percent; and young people’s support slipped from 25 percent to a low of 23 percent.

Seeing just how poorly Trump was being viewed three years ago, it’s possible that the improvement in Trump’s favorability now can be attributed in part to the fading memories of January 6 and the tumultuous year that was 2020. With time, and with Republicans rallying around Trump in the wake of his indictments, Trump’s image could only rise from the low point of January 2021.

Explanation 3: Trump is benefiting from a quieter campaign, muted coverage, and a tuned-out public

A third theory holds that Trump’s improved standing is a product of him receiving less attention than he used to get. Trump is campaigning differently, getting different press coverage, and receiving less attention from the American public.

Here, Gallup is helpful again. In their surveys asking Americans how closely they follow national politics, a key bit of context emerges: The percentage of Americans reporting they follow politics “very closely” fell to 32 percent in 2023. The 2023 figure is a nearly 10 percentage-point drop from a high of 42 percent in 2020 and 38 percent in 2021. Similarly large drops in attention appear in the data for young adults and nonwhite Americans from 2020 to 2023 (Gallup’s 2020 survey did not break down subgroups by income). These results would also help explain why so many Americans reported to pollsters for much of the primary season that they didn’t really think Trump and Biden would end up being their party nominees.

On top of this tuned-out public, there’s the relative absence of Trump in daily life. Part of the evidence for this argument is the comparatively quiet campaign that Trump has run this time around, and quieter press coverage, especially when judged against his all-consuming media presence during the 2016 cycle and the reelection campaign he started as a sitting president long before officially kicking it off in 2019. Aside from coverage of his indictments and arraignments in 2023, he does not appear to be as ever-present a figure in daily life as he used to be. Gone are the Twitter screeds and chaotic press conferences; muted is the constant coverage of his campaign rallies. He no longer commands attention as the country’s leader through a year of crisis, and his campaign events are geared toward conservative audiences, whether at CPAC, in deep-red parts of the country, or with conservative media.

Biden seems to believe some of this. In speaking to the New Yorker’s Evan Osnos, Biden apparently complained that he felt the press was neither engaging his own track record nor Trump’s “menace” adequately. In reflecting on that exchange, Osnos acknowledged the perplexing conundrum the press faces in covering Trump’s current campaign: that, at a certain point, it’s hard to communicate to the public when to pay attention to truly jarring and disturbing moments because there’s only so much Trump can do to shock. He pointed to the lack of media coverage of Trump’s first major campaign rally in Waco, Texas — on the 30th anniversary of the deadly FBI raid on the far-right Branch Davidian religious cult’s compound — where the Trump campaign played a version of the national anthem sung by incarcerated January 6 rioters while displaying images of the Capitol attack. The moment seems to have been forgotten.

So what should we make of all this?

These three explanations approach the Trump favorability question from different angles: specific to this moment in time, to the way American memory and attention works, and the extent to which individual candidates can affect and influence American minds. There could also be methodological issues as well; polling of Americans right now is a bit more difficult and seems to be tracking a lot of noise. But taken together, these theories offer a picture of just what could be happening in the electorate and why one of the most disliked figures in American politics might be getting more popular.

Sourse: vox.com