As much as any other issue, women’s health will be on the ballot in the 2018 midterm elections.

It’s almost hard to remember now, but in the days before the Affordable Care Act was in place, health insurance companies routinely charged women in America more than men. Some women were deemed uninsurable because they had preexisting conditions like pregnancy or a breast cancer diagnosis. Now Obamacare makes that illegal — but Donald Trump’s election endangered those protections.

First, Republicans tried to repeal Obamacare. Perhaps because they had more at stake, women were much more worried than men that the GOP’s health care plans would leave them worse off than they are now. But though Republicans have given up on repealing Obamacare (for now), the Trump administration has recently argued against the law in ongoing litigation that could make it all the way to the Supreme Court.

Given the high-profile debate over health care, the stakes for women, and their documented concerns about the GOP’s agenda, it doesn’t seem like a coincidence that more women are running and winning in Democratic primaries than ever before.

And based on the polling we have, if Democrats take back the House in November, they will have women voters — and their commitment to preserving Obamacare’s protections for preexisting conditions — to thank.

Obamacare ended insurance discrimination against women

Before Obamacare, health insurers in the individual market could deny women coverage because of their gender or charge them a higher premium. Only a few states made this illegal. Insurers were also freer to offer plans that didn’t cover benefits women specifically would need, like maternity care.

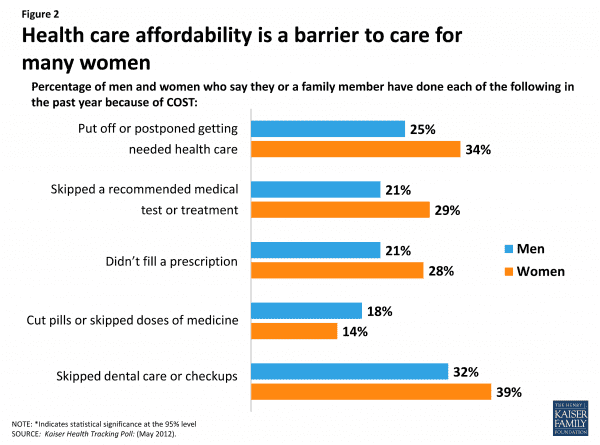

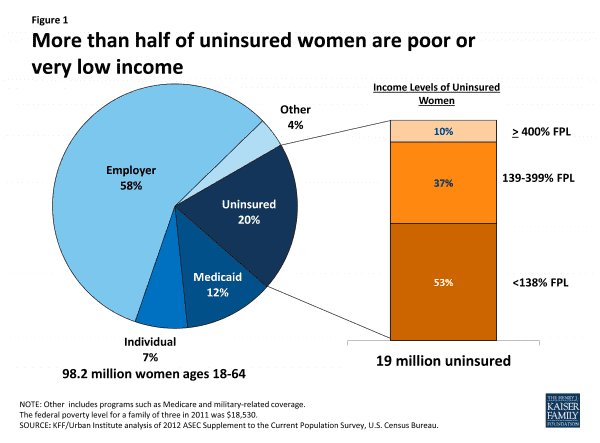

While most women, like most Americans, got coverage through work, 19 million were nevertheless uninsured before Obamacare. Women were also more likely than men to report that they had a hard time affording health care prior to the ACA’s implementation in 2013.

The Affordable Care Act changed everything. It prohibited insurers on the individual market from charging people more based on their gender or their medical history. Women are more likely than men to have a preexisting condition, which can include a history of rape, domestic violence, or even pregnancy. The law required insurers to cover certain services, including maternity care, ensuring women would be able to buy a health plan that actually covered the medical care they needed.

The law also expanded Medicaid for the poorest Americans and offered federal assistance for people who make a little more money to buy private insurance — provisions that were estimated to benefit 90 percent of the women who were uninsured in 2012, before the ACA took full effect. Because women were much more likely to be low-income, they tended to disproportionately benefit from Medicaid’s expansion.

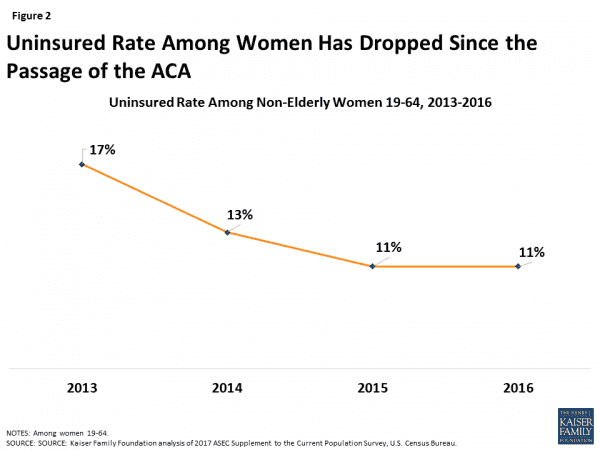

Under Obamacare, we saw the uninsured rate for women drop dramatically, even though some states refused to expand Medicaid, a decision that left an estimated 1.1 million women in poverty uninsured.

There’s no question that the Affordable Care Act dramatically improved the health and financial security of millions of women. But after nearly a decade of running on repealing the law, Republicans felt they needed to deliver on their pledge.

Trump and the GOP tried to overturn Obamacare’s protections for women

President Trump and Republicans in Congress, of course, swept into office by promising they would repeal Obamacare root and branch. They had a lot of proposals, but not a single one of the health care bills put forward actually would have done that. Still, Republicans did target the preexisting conditions protections in their various plans.

The GOP blamed the ACA’s regulations for driving up the cost of health insurance, though part of the reason costs went up was health insurers could no longer simply refuse to cover costlier patients, who are more likely to be women.

Women are more likely than men to have a preexisting condition that insurers could use as grounds to deny them coverage if Obamacare’s rules were rolled back, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation: 29.4 million women under 65, or 30 percent, versus 22.8 million men (24 percent).

Republicans tried to tiptoe around this issue in their Obamacare repeal bills, but the unavoidable truth was that they were prepared to start rolling back the law’s protections for women. Maybe as a result, women were more likely to oppose the Republican plans.

Republicans’ efforts to repeal Obamacare failed dramatically last July, but that doesn’t mean the preexisting condition rules were safe. Several states have sued to overturn Obamacare entirely, arguing that since Republicans repealed the individual mandate in their tax law, the legal rationale that saved the law at the Supreme Court in 2012 no longer applies.

The Trump administration, in a move that prompted career Justice Department attorneys to resign, agreed in part with the states, led by Texas. The Justice Department said that the mandate and the law’s protections for preexisting conditions should be invalidated by the court, with an argument that legal scholars of all ideological stripes have said is absurd.

“If the Texas lawsuit prevailed, it would be particularly bad for women because they would start to get charged more again,” Katherine Hempstead, a senior adviser at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, told me.

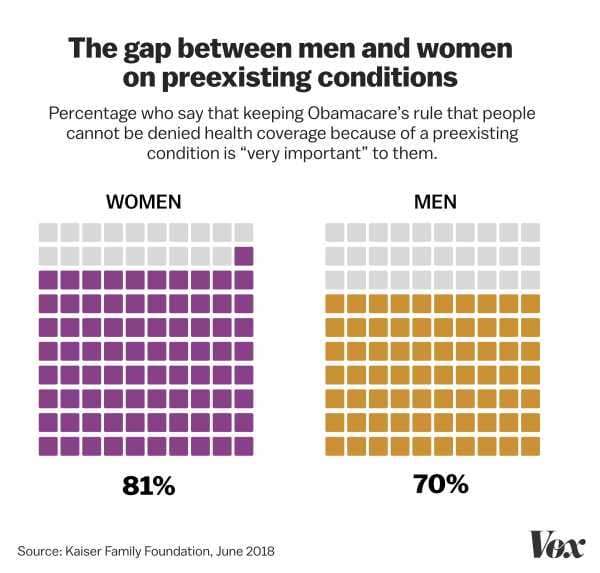

Just like with the repeal bills, women would be the big losers if the Trump administration’s argument were to win out. They seem to know it too: Recent polling has shown a notable gender gap in support for Obamacare’s preexisting conditions rules. The provisions are very popular overall, but women are more likely than men to say they’re “very important.”

Women are now driving Democratic momentum in the 2018 elections

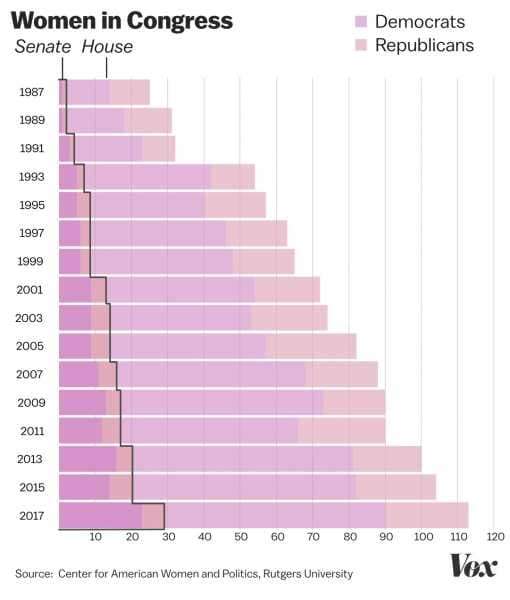

Perhaps it should be no surprise, then, that women are running and winning more than ever in Democratic primaries across the country, setting up contests against Republicans that Democrats very much want to make about health care. At the same time, a potentially historic gender gap could help sweep Democrats into control of the House.

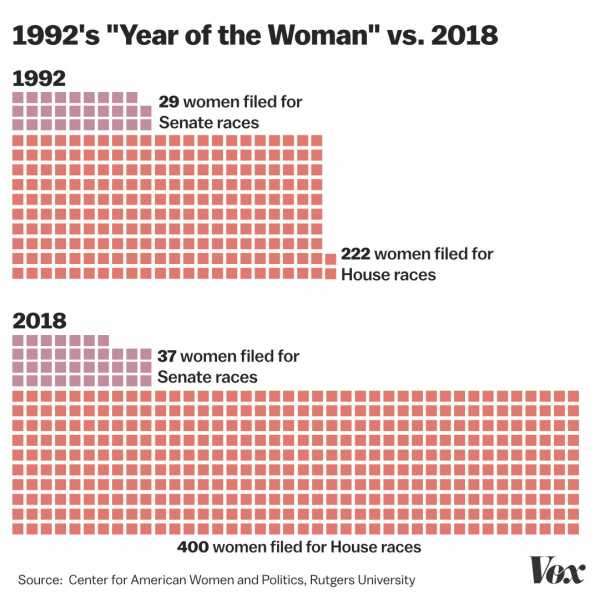

The candidate numbers are striking. Though 1992 was once billed “the Year of the Woman,” take a look at how 2018 compares. They aren’t all Democrats, but most of them are.

In a couple of cases, progressive women are running on health care — and toppling establishment-backed men in key primaries. Katie Porter, endorsed by Sen. Elizabeth Warren, beat out a single-payer skeptic in California’s 45th District. Kara Eastman, who supports Medicare-for-all, defeated a former Congress member who had the backing of Washington Democrats in the Nebraska Second.

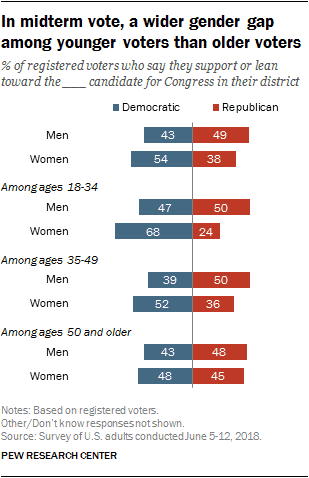

We know health care is a top issue for voters, and women — especially young women — are leaning heavily toward Democrats.

In a recent survey, the Pew Research Center found that 54 percent of women said they would vote for the Democratic candidate in the November congressional elections, and just 38 percent were planning to vote for the Republican. Among men, 49 percent said they would support the GOP candidate and 43 percent said they’d vote for the Democrat.

The Pew poll showed Democrats leading the generic ballot by 5 points, just under what election forecasters think they need to retake the House. Another recent poll, from Quinninpiac University, showed Democrats with a 9-point lead — a little above what experts think they must win by — and found a substantial gender gap.

More women candidates could mean more women in Congress, maybe a lot more if Democrats do manage to take the House.

Women and health care — not to mention opposition to an unpopular president whose other policies have been bad for women too — have conspired to give Democrats a chance in November.

Sourse: vox.com