Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

As a boy, I got into the habit of watching my father eat. Our dinner table was round, and, on the nights when it was all of us, four kids and two parents, my mother and father would sit on one side and I would sit directly across from them. The meal was mostly silent, save for the symphony of metal forks or spoons and my father, the lone vocalist, mumbling or moaning through bites. Even before a meal, he would prepare, slowly: blessing the food in Arabic, seasoning it, stretching a napkin wide. There was a point I always loved when he first set upon his plate, deciding exactly what he was going to allow himself to enjoy first. The moment never lasted more than a few seconds, but I liked seeing that even he was at odds with his own patience, divided between his desire to sprint and his ability to savor.

As long as I can remember, my father was bald, which is, in part, why watching him eat was such a singular delight. No matter the level of seasoning that was or wasn’t on his food, small beads of sweat would begin to congregate atop his head—a few small ones at first, which tumbled down his forehead or toward his ears to make way for a newer, more robust set of drops. This process would continue until, every now and then, he would pull out a handkerchief, dabbing his temples furiously with one hand while continuing to eat with the other. This is how I knew that my father was somewhere beyond, blown past the doorstep of pleasure and well into a tour of its many-roomed home.

I don’t remember when it was that I realized that the bald Black men I loved had once had hair, or that they put work into keeping their heads clean. My father and grandfather both had bald heads, and they both had thick, coarse beards that they cared for rigorously. The scent of my father’s beard oil arrived in rooms before he did, and lingered long after he left. He approached his beard care with precision and tenderness—his fingers shuffling through the hair on his chin when he spoke or listened intently, a comb almost always peeking out from his front pocket. Because I came into the world loving men who had no hair on their heads but cared for what hair they did have—bursting from their cheeks, or curved around their upper lips like two beckoning arms—it seemed that this was a kind of sacrifice made in the name of loving well, of having something that a small child could reach up and bury their hands in.

If my father worked in the back yard washing his car or hauling some wayward tree branches, his bald mound laid out for the birds to circle around in song, I could see the sunlight find a spot from which to kick its feet up, right at the crown. I was so young, and so foolish, I imagined that if I crawled high enough, on the right day, I could look down and see my own face reflected back to me from the top of my father’s shining dome, and nothing felt more like love to me than imagining this.

There’s a James Brown quote (almost certainly apocryphal) that goes, “Sometimes, you like to let your hair do the talking!” I imagine him pronouncing this as he tenderly touches his palms to the sides of an absolute monument of a pompadour, the kind he’s sporting in one of my favorite photos of him, backstage and staring into the mirror with a look of both concern and determination. When you performed the way James Brown performed, some nights it would be a miracle to have your hair stay in place, so when the crowd first saw you it had to be perfect. Per the Gospel of James, the hair speaks, and it has been true for me that Black hair (or a lack thereof) speaks in a language entirely its own. But, even among Black folks, some hair has an eloquence that other hair might not be afforded. When it speaks well, there is nothing else that needs to be said about it—although, if I know my people, I can say that many of us don’t mind heaping praise upon someone who looks good, even if he already knows it.

The first time I saw the Fab Five was before the start of their freshmen season at the University of Michigan, in 1991, when photos of the group ran in Sports Illustrated. In one, taking up most of a page in the magazine, the players are sitting on the floor of Michigan’s Crisler arena—Jalen Rose, Juwan Howard, Jimmy King, Ray Jackson, and Chris Webber—with the Michigan coach, Steve Fisher, at their center. Looking at the picture now, I can almost hear the photographer shouting out directions the way they’d shout at me and my teammates when we took our high-school sports photos: one player on one knee, arm draped over the bent knee; anyone in the front, stretch your legs across the floor. The only player breaking decorum slightly is Webber, who rests his head on King’s arm, looking like he’s either entering or exiting a laugh. The five young Black players were hailed as the best recruiting class in college-basketball history. For the uninitiated—for those not on the playgrounds or in the streets or privy to locker-room whispers about how big and bad the storm descending on Ann Arbor was—the photo was a scene of reassurance, appeasing those who feared that the Fab Five would disrupt the landscape of the game.

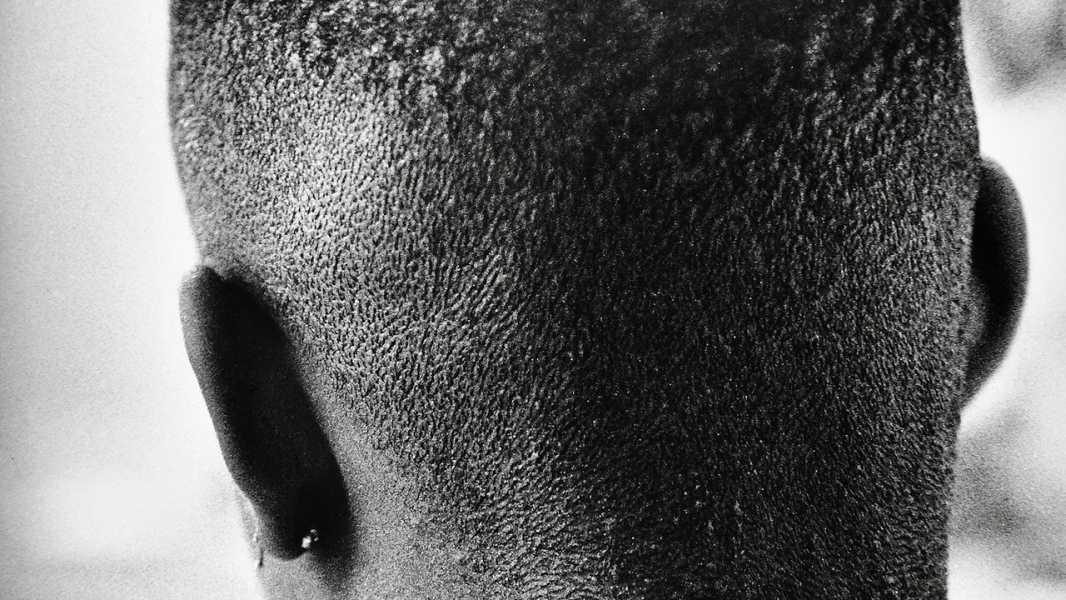

By their sophomore season, though, the Fab Five had chosen to evolve their style. Their sneakers were all black now. So were their socks. Both items went against the style of their teammates at the time, white socks rising out of white sneakers. They were a team within a team, and it wasn’t only the black socks and kicks that stood out; Chris Webber and Jalen Rose also sported freshly shaved heads. In their freshman season, both had flirted with baldness, but they’d usually kept a tight fade, just high enough to let people know that there was, in fact, hair present, its abundance stifled with intention. Now the two left no doubt. Their heads were clean and their shorts were so baggy that the fabric trailed behind them like a herd of horses during a fast break—and there were many fast breaks.

If you were to go back and look at or listen to some of the commentary from white college-basketball experts at the time, you would find an odd fixation on this baldness. It was often lumped in with the black socks and the black shoes and the baggy uniforms, all as a way of suggesting that there was something troubling about the team’s presentation and, therefore, something troubling about their approach to the game. These weren’t the people who were supposed to make it. Not this far, not this fast. Announcers, shaking their heads, decried how much time the five freshmen spent shit-talking their opponents, or sometimes one another. (You can always tell who did or didn’t grow up playing the dozens by who clutches their pearls when they see some Black folks talking shit to one another.) When the Fab Five lost, the news was met with an unspoken, and sometimes loudly spoken, glee. This, of course, only made me love them more, with an intensity that led me to understand that anyone who did not love this team, anyone who might wish to tame or temper their brilliance, was my enemy.

The early nineties had no shortage of panicked people who already feared young Black folks. But the targets of the panic knew better. I never once believed that my heroes were the villains of the story—not the ones who tucked colorful bandanas into their back pockets and slowly unfurled them once they got the fuck off school grounds, not the ones who sat in principals’ offices because they had just left the salon or the barbershop and looked too damn good to cater to anyone’s comfort but their own, not the ones who wore jean jackets with puffy letters airbrushed onto them, spelling the names of those who were no longer among us. Being young and idolizing the people whom others were trying to persuade me to be afraid of: this was the first way I felt myself maneuvering on the far side of American fear.

Today, Chris Webber’s hair is styled in neat and even knots. Jalen Rose’s is a source of awe and a butt of online jokes, the hairline so precise that if I look at it for too long, trying to figure out the math of it all, my vision begins to blur. The two have been involved in a years-long feud punctuated by brief, awkward interactions. In 2015, on “The Dan Patrick Show,” Webber lamented that his other teammates were doing films and merch to cash in on the legacy of the Fab Five.

“No one ever loved the Fab Five,” Webber said. “So why would you use us to tell stories to get that fake love now?”

If you didn’t have the money for the barbershop, someone in your crib damn well better have known how to cut hair. Someone surgical with the Wahl, someone who’d learned how to fade their own shit by holding a mirror in one hand, slightly angled to pick up the reflection from another mirror, looking both into it and behind—assessing both his present self and his potential future self—with the clippers stretched toward the back of his head. It was probably best if that someone was a someone who also carried your last name, or some kinship, so that there was just a touch of extra incentive to not fuck your head up. Any good barber took pride in his work, but that pride increased depending on how easily the results of it could be traced back to his doorstep.

In my house, the someone was my oldest brother, who cut my hair from my first haircut through to my early teen-age years. When he went off to college, I would let my hair grow until he visited for a weekend and I could persuade him to take care of my head. I believe he enjoyed being of service to his younger brothers in this way, even if he didn’t show it. He would sigh, jerk our heads around, and tightly hold them in place. But there was also a sense of care that came through when he caught a good groove with the clippers. When he was proud of his work, or even fascinated by it, you could tell. His pace slowed down, his grip on the back of my head would loosen a little bit. It was a strange pleasure, getting to act as his sometimes unruly canvas.

Almost every year that I was in school, I wore a kufi to class each day. My mother stitched them with colorful designs, working at a sewing machine that could be heard echoing throughout the house in the evenings. Because my head was usually covered outside of the house, there was no real reason to spend much time on my hair. But my brother cut my hair with a knowledge that I didn’t yet possess: that to keep a part of oneself covered sparks a fiery curiosity within others. This is to say that my hair and what it did or didn’t look like became a source of wonder for the people around me. I took a youthful and foolish pleasure in holding on to that kind of power, in having a secret that I knew others wished to see revealed.

In the seventh grade, I wanted someone who didn’t notice me to notice me, and I figured the way to achieve this was to show up to school, finally, with my head uncovered. This plan, of course, would involve getting a fresh haircut—one that I, for once, would be the architect of. And so, in the bathroom, with the door closed, I unfurled my brother’s clippers and went to work. The hairline would be done last, after I’d got the rest of my head to the desired length; I had learned that much. What I didn’t learn was about the guards that needed to be placed over the clipper blades to get the desired length, or the sound the old blades would make when they ran over a patch of hair the wrong way, a sort of growl interrupting the otherwise constant hum.

When it was all said and done, what I had inflicted upon myself was beyond repair by anyone who lived under my roof. My parents, too amused to be annoyed, gave me a little bit of money and told me to walk to the barbershop down the street. It was just enough money to get the most basic remedy for my affliction: a bald cut, a baptism of sorts. In the mirror the next morning, I looked at my own bare head and thought about the men I loved who had worn theirs so well that I’d assumed their heads had never been graced with any hair. My own baldness was jarring. The light wasn’t beckoned toward it. The top of my head seemed shadowed, hiding from its own luminescence.

In high school, after class let out, I would go to the house of a friend I’ll call Leslie. Her father worked second shift, and her mother’s name was carved into one of the headstones in a field a mile west of the school, just a few miles north of the field where I’d buried my mother two years earlier. In the fall and winter months, there would be a small break between the end of the school day and the start of whatever practices I had to get to: soccer, or basketball, or drama club. I had no car until my senior year and lived too far away to bus home and then make my way back, and Leslie lived a few short blocks away from the soccer field.

Leslie and I didn’t talk in school. We’d pass each other in the hallways, tucked into our respective friend groups, and avoid eye contact. This made our frantic encounters outside the confines of the building feel more forbidden and also more transactional. The loss of our mothers might have bonded Leslie and me in another world, one in which we were considering falling in love and not simply occupying the lonely gaps of living.

Above her bed, Leslie had a promo poster for Meshell Ndegeocello’s 1999 album “Bitter.” Some record stores at the time would keep such posters hanging in their windows in the lead-up to an album’s release. If you were smart and looking for a free way to adorn the bare walls of an otherwise unbearable childhood room, you could go into the record store on the week before the album’s release and have your name and phone number scrawled on the back of the poster. Then, when the store was done with it, it was yours.

The poster, a large reproduction of the album cover, was stunning. Ndegeocello was lying upon gold-colored bedsheets, resting on her side, with one arm propping her up. She was slightly out of focus but generously bathed in sunlight. Her head was the star of the image. Bald and half awash in that eager light, it was glowing, a clear, expansive dark brown. In the small moments when Leslie and I did talk, she would obsess over the poster. She would show me pictures of bald Black women in magazines and ask if I thought they were beautiful. She would sometimes run a hand through her dark curls with a look of surprise, as if she’d dreamed them away and couldn’t believe they’d had the nerve to reappear.

One day toward the end of the school year, rain delayed some spring sports practice that I was supposed to get to. Leslie and I sat together on her bed, and she told me that she’d borrowed hair clippers from one of the boys on the football team. She was ready, she said, to cut all of her hair off—it grows back, after all—and she wanted me to do the cutting. It was easier that way, and she knew that I at least had some limited and clumsy experience. We laid a bedsheet on the floor and then placed a chair atop it, as I’d seen my brothers do. Leslie sat down, and I wrapped her in a blanket. It escaped me then, the tenderness of the moment, which was something far beyond what we’d experienced during even our most heightened pursuits of physical intimacy.

The title track of Ndegeocello’s “Bitter” ends with the lyrics, “For us there’ll be no more / and now my eyes, they look at you / bitterly / bitterly / bitterly.” This sounds like it’s describing the end of a love affair, but I think it could be describing a present version of a self pushing a past version away—a past version who loved someone, and then buried someone, and then was never the same after. Once, when I slipped into Leslie’s older brother’s room to steal a condom, I saw her mother’s wigs in an open closet. In all the time that Leslie and I spent together, we never spoke of what had taken them from us. I never asked about the wigs, and I never asked about the cancer. I never asked about the old coat of her mother’s that never seemed to leave the coat rack by the front door. I knew what it was like to keep something like that close, just in case there was some error in the universe. Standing above Leslie, in the makeshift chair at the center of our makeshift barbershop, I moved her head into the best lighting in the room, the way my brothers had done with me a hundred times before, searching for the best place to start. When I turned on the clippers, Leslie squirmed, and so I turned them off. I turned them back on and she slid down in the chair a little bit, and so I unplugged them again. I moved to the front of the chair and sat down on the floor. We looked at each other, and Leslie’s face contorted as though she had just considered something immense for the first time.

“What if I’ve got, like, a fucking weird-shaped head?” she said.

After a pause, we began laughing. It started small, with hiccups of snorting and snickering, then became outright shouts that sent both of us rolling on the floor, knocking the chair over in our temporary madness. Laughter and crying tumble out of the body to a similar tune, and so who is to say, really, if they were ever distinct on that afternoon, the rain against the windows, keeping time with our reckless unfurling—the two of us, laughing and crying, wondering if there would ever be a time when we might find ourselves unleashed from the kingdom of vanity. ♦

This is drawn from “There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension.”

Sourse: newyorker.com