To understand the Israel-Hamas war, you have to understand how we got here.

In 1988, a Palestinian mother and child walk along the border of the Ansar II prison camp in Gaza, Israeli soldiers standing guard. Sven Nackstrand/AFP/Getty Images Nicole Narea covers politics and society for Vox. She first joined Vox in 2019, and her work has also appeared in Politico, Washington Monthly, and the New Republic.

Hamas’s attack on Israel, and Israel’s offensive in Gaza in response, is yet another escalation in a long conflict that has already left thousands dead on both sides.

The latest round of violence between Israel and Palestine began after the Palestinian militant group Hamas launched the deadliest attack on Israel ever on October 7, killing more than 1,400 people, and capturing nearly 200, by the latest estimates. Israel responded with an intense counteroffensive that included an order to carry out a “complete siege” of Gaza, and it appears to be readying for a ground assault.

Israeli airstrikes have already devastated many civilian areas, and the death toll in Gaza is growing amid a spiraling humanitarian crisis. Foreign passport holders in Gaza and aid convoys carrying life-saving supplies from Egypt have lined up at the Egyptian border crossing waiting for an agreement that would allow the border to open, but that has so far failed to materialize.

The death and destruction are the bloody culmination of decades of fighting rooted in a complicated history. To understand the current violence, you have to understand how we got here. If you’re just catching up, here are the key dates that have led up to this critical inflection point.

1917: The Balfour Declaration

The 1800s were a time of great colonial expansion as European empires jockeyed to take over other parts of the world, including the Middle East. As early as the 1840s, the British saw Palestine as an opportunity to carve out a sphere of influence in the Middle East, where they were competing with the French and Russians. But it wasn’t until World War I, in which they were fighting the Ottomans who controlled Palestine, that the British formalized their support for the idea of a Jewish state in the region.

In its 1917 Balfour Declaration, the British government unilaterally called for the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, despite the fact that Jewish people made up less than 15 percent of the population there at the time. Though the declaration vowed that “nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine,” it did not outline what those communities were, what specific rights they had, or how they would be protected, and it didn’t take their thoughts about how their land should be used into account.

The Allied powers in the war backed the declaration, and after the war, the newly created League of Nations gave Britain a mandate to temporarily rule Palestine until the Jewish state could be created.

A 1919 poster encouraging Americans to donate to the Zionist cause. US Library of Congress

The British thereafter adopted immigration policies that encouraged more than 100,000 Jews to immigrate over the next two decades.

1930s: Jews seek to flee Nazi rule, but have nowhere to go

Jews had been persecuted in Europe for centuries, but in the early 1900s, antisemitism reached a fever pitch across the continent, particularly in Germany. By the 1930s, it had became a tool of populism and the official policy of the Nazis. As the Nazi Party completed its takeover of the German government, it enacted hundreds of decrees and laws that targeted Jews as “enemies of the state” in Germany, and gradually ramped up an assault on Jewish rights.

At first, Nazis barred Jews from a swath of industries ranging from civil service to acting. Then, they prohibited Jews from marrying people of “German or German-related blood,” prevented them from obtaining citizenship in the German Reich or earning a living, and expropriated Jewish property and sold it to Nazi party officials at low prices. The Nazis’ objective was to make life so terrible for Jews that they would leave — and about a quarter of German Jews had by 1938.

That year, before World War II officially began, Germany annexed Austria and brought another 185,000 Jews under Nazi rule. Though many of them wanted to flee, few countries would have them. Representatives from 32 countries convened in Evian, France, to discuss resettlement. But while many of them expressed sympathy for Jewish refugees, most of them declined to take them in, including the US and Britain.

As Jewish refugees looked for a place to go, Zionists — activists in a movement seeking a permanent home for Jewish people — advertised and agitated for immigration to Palestine. For years, prominent Zionists had called for a Jewish state in Palestine (rather than Uganda or any other nation sometimes suggested) because of the region’s religious and historical significance to Jewish people. And the area proved popular, with the Jewish population of British-ruled Palestine increasing by more than 160,000 between 1932 and 1935 alone.

Students relax between classes at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem at what was then known as the “American Colony,” sometime in the early to mid-1930s. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection of the US Library of Congress

The influx put stress on the British occupation, and on the Palestinians already living in the area, leading to volatile and violent encounters between Palestinian and British troops, as well as their immigrant militia allies. The British even imposed harsh new immigration quotas in Palestine after seeing a record number of immigrants in 1935 driven by Nazi persecution of Jews. Those quotas remained for the duration of the war, sealing the fate of many of the 6 million Jews ultimately murdered in the Holocaust who had nowhere safe to go.

Revisionist Zionist terrorists — who went further than other Zionists in calling for a Jewish state focused on maximal territorial expansionism through force, and who were unhappy with British attempts to stem the violence by limiting immigration — also sowed chaos. All of this led to Britain looking for an eventual exit from Palestine.

1948: The formation of Israel and the “Nakba”

After World War II, tens of thousands of Holocaust survivors began moving to Palestine, encouraged by a strengthened Zionist movement. The United Nations agreed to partition Palestine into two states, one for the area’s Jewish population and another for the Arab population, with the city of Jerusalem to be governed by a special international entity. However, local Arabs and Arab countries objected to the plan.

Following a period of extreme violence before, during, and after the war — particularly on the part of Zionist militias — British forces withdrew from Palestine, and Israel declared its independence on May 14, 1948. That started the first Arab-Israeli war, in which Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria — opponents of Israel’s declaration of independence — invaded the country. Though the US immediately recognized the new provisional Israeli government, it did not get involved in the conflict militarily. Israel won the war and with it, 77 percent of the previous Palestinian mandate territory, including land that the UN had intended to allocate to the Arabs.

During the Arab-Israeli war, and in the militia attacks that preceded it, more than 700,000 Palestinians were forced to flee and approximately 15,000 were killed in what Palestinians refer to as the “Nakba,” Arabic for “catastrophe.” It’s a formative event for Palestinian identity and has been observed annually in the years since — including by the United Nations for the first time in 2023. Some have warned that the current Israeli offensive in Gaza, in which more than 1 million Palestinians have been told by Israel to flee, is amounting to a “second Nakba.”

1950s: The Lavon affair and the Suez Crisis

In 1954, Israel sought to carry out a covert operation against Egypt. The so-called “Lavon affair,” named for Israel’s then-defense minister, involved planting bombs inside targets owned by Egyptian, American, and British civilians with the intention of detonating them after the facilities closed and placing the blame on nationalist malcontents, including the Muslim Brotherhood. Israeli operatives recruited Egyptian Jews to carry the plan out.

Their objective was to stir up sufficient strife so as to persuade the British to keep their forces in Egypt at a moment when the two countries were negotiating Britain’s exit from the Suez Canal. Israel feared that Britain’s departure would embolden Egypt militarily in the region, threatening the new state. But after detonating the bombs, Israel’s operatives were caught. Two died by suicide in prison, and another two were executed by Egypt. Others faced lengthy prison sentences.

Egypt’s treatment of the saboteurs led Israel to launch a retaliatory incursion into Gaza, then controlled by Egypt, and Egypt took steps to better arm itself against the Israelis. After the US and Britain refused Egypt’s request for military assistance, Egypt turned to the Soviet Union, which provided that assistance. That made the US and Britain furious, and they consequently withdrew funding in 1956 for Egypt’s Aswan Dam project, which was the largest dam project in the world along the Nile. Egypt retaliated by nationalizing the Suez Canal, which made it difficult for Western nations to access trade routes and their colonies, setting off what is now known as the “Suez Crisis” or the “Tripartite Aggression.”

British soldiers guard a checkpoint in Ismailia, a city nestled against the Suez Canal. PA Images/Getty Images

That conflict saw Israel, and then Britain and France, invade Egypt and Gaza in order to reclaim control of the Suez Canal and remove the Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser. But following pressure from the US and UN, those forces withdrew, and Nasser remained in power. There was no peace treaty after the conflict, and tensions between Egypt and Israel remained high, setting the stage for the country’s next conflict. The UN also stationed peacekeeping forces along the Egypt-Israel border.

1967: The Six-Day War

The 1967 war, also known as the Six-Day War, reshaped the Middle East and established Israel as a dominant military power in the region. It was the culmination of long-brewing tensions in the region between Israel and other regional powers.

The conflict started after Egypt closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli vessels amid disagreements with the Israelis over water rights. But other actors also saw reason to get involved: Syria, which was engaged in territorial disputes with Israel over the Golan Heights border region, supported Palestinian guerillas in leading incursions into Israel. Jordan entered into a defense pact with Egypt to show solidarity with Arab states against Israel, and wanted to reclaim territory it had lost in the 1948 war.

The conflict saw Israel defeat all of those countries, suffering comparatively few casualties in the process with little help from outside forces, and occupy swaths of new territory, including Gaza, the West Bank, the Sinai Peninsula, parts of East Jerusalem, and the Golan Heights. It did so by launching a preemptive strike on Egypt, destroying much of the country’s air force before it left the ground and giving Israel the aerial advantage.

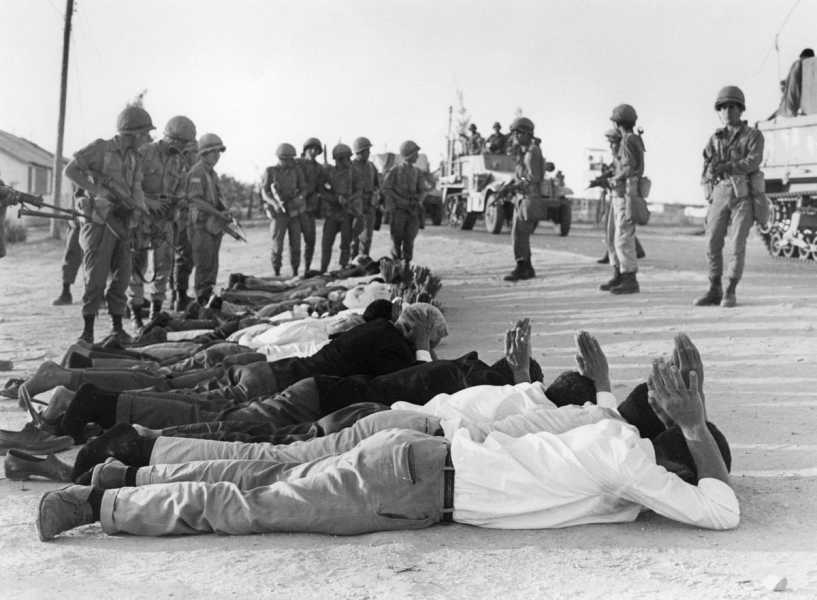

Israeli soldiers watch over a group of Palestinians who surrendered to them in the occupied West Bank on June 5, 1967. Pierre Guillaud/AFP/Getty Images

The US had been concerned about Soviet influence in the region, particularly in Egypt, and worried that the conflict could have expanded into a Cold War proxy battle if it had escalated further. But Israel put a quick end to it — and made itself an attractive ally at a moment when the US wanted to squash communism everywhere, but was preoccupied with the Vietnam War and did not have the bandwidth to get involved militarily in the Middle East. The end of the Six-Day War marked the beginning of the US and Israel’s relationship as close allies.

The UN adopted a resolution at the end of the war, known as UN Resolution 242, that called on Arab countries to recognize Israel’s right to “live in peace within secure and recognized boundaries free from threats or acts of force,” as well as calling for Israel to withdraw from “territories occupied” in the conflict. Israel, Egypt, and Jordan all came to accept the resolution, and it formed the basis of peace talks in the decades thereafter, despite the fact that its tenets were never fully implemented.

However, the agreement wasn’t accepted by Palestinian militants. The decade thereafter saw them turn to terrorism as a tactic against the Israelis. In 1972, for instance, Palestinian “Black September” gunmen killed 11 Israeli athletes at the Munich Olympics.

1973: The Yom Kippur War

Egypt and Syria launched a simultaneous, surprise attack on Israel on October 6, 1973, with the intention of forcing the country to the negotiating table to cede control of the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights. Israel had occupied Syria’s Golan Heights, located on Israel’s eastern border with Syria, and Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, located along Israel’s southern border, since the Six-Day War. The attack marked the beginning of what is called the Yom Kippur War because it commenced on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in Judaism.

The war was a shock to Israelis who, having just a few years before handily defeated their Arab neighbors, were caught unprepared. Many have drawn parallels between the Yom Kippur War and Hamas’s 2023 attack, in that respect.

A building in Damascus, Syria, half destroyed by an Israeli strike on October 10, 1973. AFP/Getty Images

After quickly depleting their reserves of munitions, the Israelis turned to the US for help. Though initially reluctant to engage, then-US President Richard Nixon sent Israel supplies and equipment when he found out that the Soviet Union was helping resupply Egypt and Syria. A UN-brokered ceasefire ended the fighting a few weeks later.

But it wasn’t until 1978 that Egypt and Israel, with the help of then-US President Jimmy Carter, arrived at a framework for lasting peace in the Camp David Accords. The accords were the blueprint for the peace treaty that the two countries signed the following year, in which Israel agreed to withdraw from Sinai and Egypt opened the Suez Canal to Israeli ships that had been previously blocked.

1982: The First Lebanon War

In the 1980s, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) was a coalition of Palestinian nationalists that had been exchanging fire with Israeli forces along the Lebanese border. They used Lebanon, home to many Palestinian exiles, as their base between the 1960s and early 1980s, though were unaffiliated with the Lebanese government.

In 1982, the Iraq-based Abu Nidal group — a brutal, militant offshoot of the PLO — orchestrated an assassination attempt on Israel’s ambassador to Britain, who was a passionate advocate for the Israeli state. Israeli forces cited the failed assassination when seeking the elimination of all Palestinian groups from Lebanon thereafter.

At great human cost, Israel invaded southern Lebanon, conducting a prolonged siege on the Lebanese capital of Beirut that led to many civilian casualties and widespread destruction. Israeli officials also permitted allied Lebanese Christian militias to enter the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila in Beirut in order to root out PLO fighters. While Israeli soldiers had the camps surrounded, those Christian militias — which hated the Muslim Palestinians — massacred hundreds, if not thousands, of civilians. Those incidents were widely condemned by the international community.

The war officially ended with a US-brokered agreement in 1983, which allowed the PLO to relocate to Tunisia. But Lebanon remained unstable. American and French peacekeeping forces, stationed in Lebanon to ensure the safety of the PLO as they exited and the remaining Palestinians, withdrew from Lebanon following the 1983 bombing of their Beirut barracks by Islamic Jihad, a Lebanese Shia militant group. Israel also gradually withdrew from Lebanon starting in 1985 and created a security zone in southern Lebanon, which it occupied for years. That area ultimately became a hot spot of terrorist activity by Hezbollah, the Iran-backed Shia militant group that opposes Israel.

1987–1993: The First Intifada, culminating in the Oslo Accords

In 1987, Palestinian frustrations had reached a boiling point following the war in Lebanon and the construction of new Israeli settlements and increased repression by Israeli security forces in the West Bank and Gaza. Palestinians staged an intifada, Arabic for “shaking off,” of Israeli oppression, engaging in nonviolent mass protests that often turned into violent clashes with Israeli security forces.

The uprising continued until the early 1990s, at which point about 2,000 people had been killed. With the support of the US and other nations, Israeli and Palestinian leaders began negotiating a peaceful end to the conflict. In 1991, representatives from the US, Soviet Union, Israel, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan, as well as non-PLO Palestinian delegates, convened for the first time in Madrid to hold negotiations that created the framework for the peace process.

That eventually culminated in the Oslo Accords, signed in 1993, which allowed Palestinians to self-govern in the West Bank and Gaza and established the Palestinian Authority as the government of those areas. Israel agreed to withdraw its security forces from those areas, and in exchange, the PLO recognized the state of Israel and the right of its citizens to live in peace.

The signing of the Oslo Accords at the White House, on September 13, 1993. J. David Ake/AFP/Getty Images

The Oslo Accords were supposed to set the stage for a two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict within five years. But that solution never came to be.

2000–2003: The Second Intifada

The Second Intifada brought an end to the era of peace talks between the Israelis and Palestinians throughout the 1990s. It began with right-wing Israeli Likud party leader Ariel Sharon’s visit to the al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem, a holy site for Muslims — as well as for Jews, who know it as the Temple Mount. Sharon was a staunch advocate of Israeli sovereignty, and Palestinians perceived his visit as a provocation because he was accompanied by Israeli police.

Then-Likud party leader Ariel Sharon leaves the al-Aqsa mosque on September 28, 2000. Awad Awad/AFP/Getty Images

Palestinians started protesting, initially mostly peacefully. Israel responded to the protests by firing at protesters with rubber bullets and later live ammunition, and sent tanks and helicopters into Palestinian areas. Within a month, the protests had morphed into violent resistance, escalating to suicide bombings and shootings inside Israel’s internationally recognized borders. In response, Israel reentered Gaza and the West Bank, ending the post-Oslo status quo, and constructed a reinforced security barrier.

A ceasefire was declared in 2003, but not before significant loss of life. More than 4,300 people died, mostly Palestinians, and the intifada caused billions in economic damage. Multiple attempts at peacemaking — the Mitchell Report, the Tenet Plan, and the road map to peace — failed to gain traction in this period.

2005: Israel temporarily withdraws from Gaza

Sharon became prime minister in 2001, and in 2005, his government announced an Israeli “disengagement plan” for Gaza that involved the complete unilateral withdrawal of Israeli settlements and military forces. Approximately 8,500 Israeli settlers — some of whom had lived there for decades and resisted the plan — were removed from their homes, and some of them were compensated. Israel ceded control of Gaza to the Palestinian Authority, led by President Mahmoud Abbas. It also vacated four Israeli settlements in the West Bank.

The objective of the withdrawal was to improve Israel’s security and create the conditions for lasting peace. Essentially, the idea was that removing soldiers and settlers from the equation would deescalate the situation and allow for real peace talks. But that wouldn’t come to pass.

2006: The Hamas takeover of Gaza and the Second Lebanon War

As part of the Oslo Accords, the occupied Palestinian territories — Gaza, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem — were meant to be governed in part by the PA’s legislative branch, which has power over civil matters, internal security, and public order. For all of its existence up until 2006, the PA had been dominated by the secular Fatah party, which recognizes the state of Israel and has sought to negotiate with it after renouncing armed resistance in the 1990s. That changed in the 2006 elections when Hamas won a majority of council seats.

Hamas supporters celebrate the group’s electoral victory in January 2006 following the announcement of the results. Jamal Aruri/AFP/Getty Images

Because of Hamas’s history of armed confrontation with Israel and its objective of destroying the Israeli state overall, the international community refused to recognize the Hamas-led government. The US went on to organize a violent coup against Hamas, promising $86 million in military assistance to Fatah commander Mohammed Dahlan’s forces. After the two parties failed to reach a lasting power-sharing agreement, a brief civil war broke out between the military wings of Hamas and Fatah, as well as their allied militias.

Hamas defeated Fatah’s forces, and though the group’s democratically elected lawmakers were expelled from the legislative council, Hamas took control of Gaza while Fatah kept control of the West Bank. Israel instituted a blockade of Gaza thereafter.

Later that year, Hamas kidnapped Gilad Shalit, a soldier in the Israeli military, and took him into Gaza. The Israeli army launched airstrikes at Gaza in response, and it wasn’t until 2011 that they were finally able to secure his release by exchanging more than 1,000 Palestinian prisoners.

The year 2006 also brought conflict in Lebanon. With the stated hope of advancing the Palestinians’ cause, Hezbollah attacked Israeli soldiers, and Israel responded with airstrikes targeting Hezbollah’s operations in Lebanon, along with limited ground incursions in southern Lebanon. And Hezbollah, which is designated as a terrorist organization by the US, shot back with a barrage of rockets that hit several cities in northern Israel. The crossfire went on for a month, displacing hundreds of thousands of Israeli and Lebanese civilians from their homes and resulting in more than 1,150 casualties total on both sides.

The fighting ended with a UN resolution that required Israeli forces to withdraw from southern Lebanon, while 30,000 Lebanese and UN peacekeeping troops took over the area to prevent the rearming of Hezbollah. Israel began developing its Iron Dome short-range missile defense system in response to the conflict.

2008-2014: Wars in Gaza

Despite agreeing to a ceasefire with Hamas just months prior, Israeli soldiers launched a raid into Gaza to kill Hamas militants in November 2008. That led to increased tensions and Israel’s decision to launch Operation Cast Lead, a weeks-long assault on Gaza involving aerial bombing and a ground invasion. The casualty figures are disputed, but it left at least 1,000 Palestinians and 12 Israelis dead. It also caused severe damage to housing, businesses, and electrical infrastructure in Gaza.

UN officials later found that the Israeli military committed war crimes and crimes against humanity in the operation, including using white phosphorus in populated areas and intentionally targeting civilians. The UN said that Palestinian militants had also committed war crimes by shooting rockets at Israeli civilians.

Violence flared up again in 2012, after an increase in Hamas rockets launched from Gaza to Israel. Israel retaliated with eight days of airstrikes and killed the head of Hamas’s military wing. Almost 180 people, mostly civilians, died in the fighting. Both sides again were found to have committed war crimes by the UN. Though Egypt helped broker a ceasefire, it was short-lived.

Hamas officials prepare to battle a blaze begun by an Israeli airstrike in Gaza, on June 23, 2012. Mahmud Hams/AFP/Getty Images

In 2014, Hamas kidnapped and killed three Israeli teens from the West Bank. In response, Israel launched airstrikes, ground operations, and naval blockades in Gaza. Though Israel’s stated target was Hamas militants and their infrastructure, thousands of Palestinians were killed in the fighting, which persisted for seven weeks. Hamas launched rockets of its own into Israel, most of which were intercepted by the Iron Dome.

Again, a ceasefire brokered by Egypt ended the conflict. But it left Gaza with significant infrastructure damage and shortages of basic necessities, with no end to the Israeli blockade in sight. At least 2,200 people were killed, the vast majority of whom were civilians in Gaza. Outbreaks of violence continued in the years thereafter.

2021: A major escalation in East Jerusalem and Gaza

Another major outbreak of violence occurred in 2021, after Israel threatened to evict Palestinian families from their homes in the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of East Jerusalem — home to holy sites of significance for Jews, Christians, and Muslims — and Israeli police imposed restrictions around the al-Aqsa Mosque during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

A coalition of Palestinian, Israeli, and international protesters gather in East Jerusalem to demonstrate on behalf of Sheikh Jarrah’s Palestinian population on March 19, 2021. Ahmad Gharabli/AFP/Getty Images

Palestinian protesters and Israeli police violently clashed in East Jerusalem, giving way to a broader conflict. Hamas fired rockets at Jerusalem, and Israel responded with airstrikes on Gaza. Again, Israel stated it only wanted to target Hamas and its infrastructure, but its offensive resulted in more than 200 civilian casualties.

After 11 days, the fighting ended with a ceasefire brokered by Egypt and Qatar. But Palestinian frustrations were left unaddressed, and outbreaks of violence between the Israelis and Palestinian militants continued.

2023: Attempts at normalization in the Middle East falter amid a new war

In recent years, Israel has been a key pillar of the US’s stated goal to create an “integrated, prosperous, and secure Middle East” as it looks to move on from long wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to turn its focus to other parts of the world, including Russia and China.

Though US-led talks between Israel and the PA froze in 2014, the Trump administration facilitated agreements to “normalize” relations between Israel and several of its Muslim-majority neighbors, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, and Morocco. These normalization efforts are aimed at establishing diplomatic and economic channels between the countries. The Biden administration also sought to normalize relations between Israel and its main regional rival Saudi Arabia so that they could form a united front against Iran, a common adversary that financially supports Hamas.

Hamas’s brutal attack on October 7 and Israel’s brutal response in Gaza, however, seem to have derailed that progress toward stability in the Middle East. This Israel-Hamas war has been the deadliest yet for both sides. Both Israel and Hamas seem to have already committed war crimes. Israel, projecting strength in the face of its failure to thwart Hamas’s attack, wants to eliminate Hamas for good and has proved willing to claim civilian lives to achieve that.

Gaza residents survey the damage from an Israeli airstrike as they look for survivors on October 19, 2023. Mustafa Hassona/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images

Mass protests have broken out worldwide, including in neighboring Arab nations that see the US as complicit in Israel’s atrocities against Palestinians. There are fears that the war could broaden to Lebanon as violence with Hezbollah flares up along Israel’s northern border. And Iran has threatened “preemptive action” by the “resistance front,” seemingly referring to Islamist militant groups such as Hezbollah, against Israel as it gears up for a ground invasion.

It’s hard to see a way out now. Any ceasefire may hinge on the US exercising its influence over Israel to stop the violence and keep the conflict from escalating further.

Sourse: vox.com