Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Photograph by Erich Karnberger / Getty

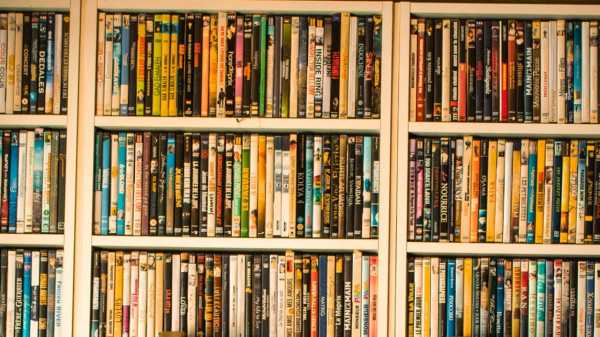

To have or not to have, that is the question. The problem with having is obvious when looking around at the many shelves for books and CDs and the filing cabinet for DVDs that line the walls and fill floor space at home. It’s especially an issue for city people whose apartment space is at a premium and who lack basements or attics or (imagine!) a spare room to hold their hoard. Ditching physical media in favor of streaming is a liberation of sorts—an unburdening that goes beyond clutter and, in a sense, lightens life itself. It’s a moveable feast for those who live precariously and for others who travel often. In Michael Mann’s thriller “Heat,” Robert De Niro delivers this line: “A guy told me one time, ‘Don’t let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in thirty seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner.’ ” So much for the personal library. At least he’ll have his Criterion Channel subscription.

I was out of town for a couple of weeks recently, and I had my subscriptions, too. The permanent smorgasbord of streaming services, whether of movies or music, is a diabolical temptation. Curiosity is easy to satisfy—at least within the wide limits of what’s available. Moreover, a month’s subscription to the Criterion Channel costs less than the purchase of any one Criterion Collection disk, while offering access to hundreds of classics. Even a small basketful of various subscriptions would likely add up to less than one might easily spend on a batch of CDs or DVDs or Blu-rays (not to mention the devices to play them on). Not only is streaming a good deal; given the huge losses recorded by many major streaming services, it may be too good a deal, as suggested by the surprising news this week—even as Netflix is ending its original DVD-by-mail service—that Bob Iger, the C.E.O. of Disney, is contemplating restoring physical media to the company’s offerings.

There’s an element of duty in a critic’s personal library, the preservation of what may prove useful for work, but it’s not the prime motive for compiling one (as I’ve been doing since childhood). Collecting is an act of love; even though it risks fetish-like attachments to the objects in question, its essence is found not in the objects themselves but in the pleasure that they provide, by delivering movies, music, literature—by providing the experience of art. Yet the experience of art is, above all, an experience, a part of life, and, just as the arts are more than mere nutrients, the medium is more than a delivery system: it has an aesthetic and a psychology of its own. The prime factor of home video is control, and it’s the struggle for control, between corporate entities and individual viewers, that’s at play in the shift from physical media to streaming.

First, even the most bountiful streaming services give with one hand while taking with the other. For example, the Criterion Channel, the gold standard for cinephilic offerings, both announces a new batch of films arriving on the first day of the following month and thoughtfully warns subscribers of what’s leaving on the last day of the current one. (Among the August 31st farewells is a large batch of Buster Keaton’s features and shorts, Martin Scorsese’s “Mean Streets,” Stanley Kwan’s intricate docu-fictional bio-pic “Center Stage,” and a group of films featuring Marilyn Monroe, including “Monkey Business” and “All About Eve.”) This is not a knock on any particular service, but it is a reason to be wary of exclusive reliance on all streaming services. There is an implicit permanence to owning a disk. (Even obsolete media, such as VHS tapes or 78-r.p.m. records, can still be played.) With streaming, availability is out of one’s control and movie-watching becomes an activity conducted under the aegis of a big brother, however well-meaning.

And that invisible hand isn’t always so benign, as indicated by ominous messages that sometimes pop up at the start of films to proclaim—as, for instance, has been seen on Disney+—that “this film has been modified from its original version. It has been edited for content.” What vanished? Sex? Drugs? Cigarettes? Hateful dialogue? “Pervasive language”? Only by watching side by side with a DVD can one find out. The oddly intrusive feeling of each viewing being mediated—by a business standing between oneself and the viewing, the listening, the reading—bears a chill of surveillance. That’s not the case when one holds in one’s lap a book that one owns, pops a disk into a player, or lays a needle on a record. Along with the specific aesthetic of movies one views, there’s an economic aesthetic at work, too, in each type of transaction: having a movie in hand that’s paid for once, or paying forever and owning nothing but memories and promises.

A collection of physical media is a bulwark against fear—the fear that rights holders may take works out of circulation, whether because of a mere contractual lapse or a calculated market-making and desire-stoking scarcity. For decades, starting long before the age of home video, Howard Hawks’s “Scarface” and Alfred Hitchcock’s “Vertigo” were unavailable in the United States for theatrical screenings. In their absence, the cinephilic world didn’t stop spinning, but it was smaller, narrowing the realm of knowledge and the spectrum of pleasure alike. The sense of crisis that always marks the interface of art and power has grown all the sharper in recent years, with the sudden disappearance of Web sites and distributors (such as Filmstruck and New Yorker Films) and the mighty archive of work that they harbor, and the mergers and takeovers of sites, publications, movie and record companies, and book publishers by owners with commercial or ideological agendas that conflict with the preservation and availability of archives. The shutdown or lockdown of a single site may eliminate all access to the only extant source for a major movie. Thus, physical media take on an essentially political role as the basis for samizdat, for the preservation in private of what’s neglected or suppressed or destroyed in the public realm, be it through mercantile vandalism, doctrinaire censorship, or technological apocalypse.

The modern history of movies started in the nineteen-thirties, when Henri Langlois and Georges Franju founded the Cinémathèque Française and Iris Barry established MOMA’s Film Library. Most movie companies at the time treated their film prints as literal throwaways to be recycled for their chemical ingredients—on the assumption that these movies, once released and exhausting their first runs, had no further value. The future of the cinema, its advance into the forefront of modern art, resulted from the preservation and appreciation of its past. In an era when cheap physical media such as DVDs circulate widely, preservation is no longer the exclusive province of institutions housing bulky and expensive film prints. The archive of the future is decentralized, crowdsourced. Far from being nostalgic and conservative, the maintenance of a stock of physical media at home is a progressive act of defiance. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com