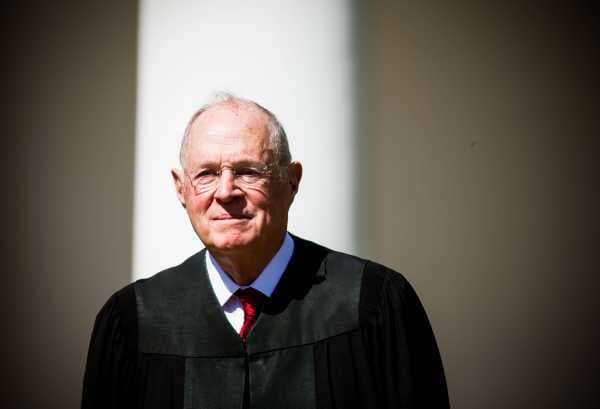

Anthony Kennedy, the longest-serving member of the Supreme Court, is reportedly considering retirement.

Kennedy has, since at least 2005, been the swing vote on many of the Court’s most ideologically charged decisions, responsible for 5-4 rulings that legalized same-sex marriage, preserved Roe v. Wade, upheld warrantless wiretapping, blew up campaign finance restrictions, overturned DC’s handgun ban, and weakened the Voting Rights Act. That position has made him one of the most powerful people in America for well over a decade now, not even counting the 18 years he shared his position as the Court’s swing voter with Sandra Day O’Connor.

But Kennedy, who turns 82 this July, is already the 14th longest-serving justice (out of 113) in the Court’s history. President Donald Trump reportedly nominated Neil Gorsuch, a former Kennedy clerk, to the Court in part to reassure Kennedy that he could trust Trump with picking his replacement. And it’s not clear that Kennedy will ever get a better time to retire, from his perspective. He’s to the left of Trump on a number of issues, but still a conservative, so he’s unlikely to be pleased with the replacement a Democratic president would pick either.

If Kennedy does retire, the Court’s decisions on issues where he’s a down-the-line conservative — like campaign finance and corruption, most business regulation and voting cases, gun rights, religious liberty, etc. — likely won’t change. There’s already a 5-4 conservative majority on those, so conservative rulings like the ones Kennedy wrote or joined in DC v. Heller, Citizens United, or Hobby Lobby will continue apace.

What will change are rulings on issues where Kennedy has helped maintain a shaky 5-4 center-left consensus. Because of the court’s longstanding principle of stare decisis, or obeying past precedent barring a compelling reason not to do so, some liberal Court achievements are likely to stay. But a Court without Kennedy is substantially more likely to:

- Overturn Roe v. Wade and allow states (and maybe the federal government too) to ban most or all abortions.

- Reject challenges to capital punishment and solitary confinement.

- Rule in favor of religious challenges to anti-discrimination law, and perhaps, in an extreme case, reverse some past Supreme Court rulings on gay rights.

- Bar government actors from engaging in explicit race-based affirmative action.

And there are likely to be more aftershocks that are hard to anticipate this far in advance.

An America after Anthony Kennedy looks significantly different from America before. The movement against mass incarceration could run into unprecedented resistance from the Court, and the anti-abortion movement could notch its greatest victories in a half-century. (And note that because the issues affected are those with a current liberal majority, the same effects are likely to obtain if one of the Court’s four liberals — Stephen Breyer, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Elena Kagan, and Sonia Sotomayor — retires or passes away.)

Unless a conservative like John Roberts, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, or Gorsuch announces a shocking early retirement, the next Supreme Court vacancy will give Donald Trump the power to shift jurisprudence on a range of critical issues. It could wind up being the most important part of his legacy.

Abortion in America after Kennedy

Nothing is guaranteed, but if Anthony Kennedy retires under Trump, his replacement will be much likelier to join a decision overturning Roe v. Wade and giving states the ability to ban abortions as early as the first trimester.

This may take years after the replacement’s confirmation; a state would need to pass a law clearly incompatible with the Court’s existing approach to abortion rights and wait for the challenge to reach the Supreme Court before the new justice would have a chance to join a ruling. The anti-abortion movement might choose a more cautious strategy, instead chipping away at Roe with measures that fall short of outright bans. But with Kennedy gone, the votes for an outright reversal of Roe would probably be there.

If Kennedy (or one of the liberals) leaves the court, UC Berkeley law dean and constitutional law expert Erwin Chemerinsky writes, “There almost certainly will be a majority to overrule Roe v. Wade and allow states to prohibit abortions.”

It’s certainly possible that Chief Justice Roberts will decline to join an anti-Roe majority due to precedent and a desire to avoid a massive public backlash, but there are reasons to think it unlikely. Roberts has on two occasions joined decisions overturning past Supreme Court precedent: one was a case on the right to counsel and how it can and cannot be waived, and the other was Citizens United, which sparked massive national outrage.

Roberts voted to overturn precedent anyway, knowing a backlash was inevitable. Indeed, in his concurrence to Citizens United, Roberts suggested that “hotly contested” issues might provide for exceptions from the principle of stare decisis and respect for precedent. Also possible is that instead of decapitating Roe in one blow, Roberts will instead “vote to kill it with 1,000 cuts rather than overturn it outright,” as UC Irvine Law’s Richard Hasen puts it.

Perhaps we’ll see another case like Whole Women’s Health (a 2016 decision where Kennedy joined the Court’s liberals in striking down Texas regulations meant to disrupt abortion provision), but this time the court sides with the state’s restrictions. Perhaps another state takes its 20-week ban to the Supreme Court, which then relaxes Roe and rules that you can bar abortions that early in a pregnancy. Bit by bit, the Court enables states to get more creative and bold in their restrictions, until one day it finally gives up the ghost and announces Roe is dead.

In the aftermath of a reversal, the current gap in abortion services between red and blue states will become even more severe. The pro-abortion rights Guttmacher Institute classifies 29 states as “hostile or extremely hostile” to abortion rights, of which all but two voted for Trump in 2016 (the exceptions are Rhode Island and Virginia). It rated only 12 as supportive, with Montana the only supportive red state.

There are already substantial gaps between states in access to abortion. A study by Guttmacher researchers found that while the average American woman aged 15 to 44 lives fewer than 11 miles from the nearest clinic, that number varies dramatically from state to state and county to county. In Mississippi, the average woman lives 68.8 miles from the nearest clinic. In North Dakota, the number is 151.6. A lot of the variation is just a function of how rural the state is, but the political environment appears to be a significant factor as well.

Overturning Roe would harden these gaps between states, and also open up a vast new market for self-induced abortions. That market already exists. Seth Stephens-Davidowitz, an economist and writer who has conducted research on demand for abortion using Google search data, once told Vox, “I was blown away by how frequently people are searching for ways to do abortions themselves now. These searches are concentrated in parts of the country where it’s hard to get an abortion and they rose substantially when it became harder to get an abortion.”

But while “self-induced” conjures up images of wire hangers and back alleys, the form this will most likely take is greater usage of abortion pills. About a third of all abortions, and a higher share of early-term abortions, are medication abortions now. It’s possible that’s what some of the searches for “self-induced abortion” were about, anyway.

How much do you want to bet that the US market for RU-486, purchased from online pharmacies or other dubiously legal means, will explode in the aftermath of Roe falling?

Prisons and the death penalty in America after Kennedy

Currently, there appears to be a five-justice majority on the Supreme Court for sharply limiting solitary confinement in America. Should Kennedy retire, that majority would evaporate, likely replaced with a harder-line majority that could preserve the practice.

In 2015, Anthony Kennedy filed a concurring opinion in Davis v. Ayala, a death-penalty case in which the Court (joined by Kennedy) sided against the defendant. Nevertheless, Kennedy used his concurrence to unleash a bracing jeremiad against the evils of solitary confinement, in which the defendant had been held for most of his 25-plus years in prison.

”Research still confirms what this Court suggested over a century ago: Years on end of near-total isolation exact a terrible price,” Kennedy wrote. “In a case that presented the issue, the judiciary may be required, within its proper jurisdiction and authority, to determine whether workable alternative systems for long-term confinement exist, and, if so, whether a correctional system should be required to adopt them.”

The implication was clear: Kennedy wanted advocates to bring a case challenging the constitutionality of long-term solitary confinement on the grounds that it constitutes cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment. He basically dared them to, and suggested that if such a case reached the Court, he’d be inclined to limit the practice.

Sharon Dolovich, a law professor at UCLA and faculty director of the university’s Prison Law & Policy Program, told me in 2016 that solitary confinement was the “one major unresolved issue” in criminal justice “that is definitely going to come up” in the next few years.

It’s a long time coming. At any given moment, about 80,000 to 100,000 people are held in solitary confinement in the US; in many states, the average stint in solitary lasts years. And it’s been that way at least since the 1980s, without any federal court intervention to halt it.

”There’s so much data now — physiological data, psychological data, reentry data — there’s so much data making clear the extended physical, psychological, and emotional trauma that people suffer in extended solitary confinement, it would be so easy for the Court just to point to it all and conclude there’s an objective harm,” Dolovich said.

Jonathan Simon, a law professor and director of the Center for the Study of Law and Society at UC Berkeley, also speaking in 2016, told me that solitary confinement is on “the verge of being found unconstitutional, at least in its most excessive forms.” Just what “excessive” means there is, naturally, a matter of debate, and Simon cautions that the Court could err on the side of giving prisons too much leeway.

He noted that Ashker v. Brown, a recent case challenging solitary confinement in California that ended in a settlement rather than reaching the Supreme Court, “involved a class of inmates that had been held more than 10 years, and the settlement will still allow people to be held up to five years, and even after that they can still be held in solitary if they’re given programming and special services.” By contrast, the United Nations special rapporteur on torture has called for an absolute ban on solitary confinement lasting 15 days or more. “I’m not sure Kennedy or any justice would go nearly that far,” Simon says.

But without Kennedy on the court, a ruling going even as far as a five-year maximum becomes less likely.

Solitary confinement is not the only case where a more conservative justice could make a difference. In 2011, Kennedy wrote a 5-4 decision upholding a lower court order that California release tens of thousands of prisoners to reduce overcrowding, which the state itself admitted was unconstitutional. It was, Simon told me, “the first prisoners’ rights decision to come down in favor of the prisoner in a long time. It ended mass incarceration in California.” More decisions like that could come if Kennedy stays on the court

Kennedy is also the best hope that opponents of capital punishment have for a ruling against the practice, even though he’s often sided with conservatives in some past death penalty cases on the constitutionality of, say, using a particular lethal injection method.

Back in 2016, Simon told me that he was “somewhat optimistic” that Kennedy would join with Breyer and Ginsburg (who have already declared their belief that capital punishment is across-the-board unconstitutional), Sotomayor, and Kagan in an anti-death penalty case. “The reason … goes back to his interest in dignity,” Simon said. “The strongest of the opinions in Furman” — the 1972 case that briefly abolished capital punishment — “was William Brennan’s, and Brennan based it most directly on human dignity. He argued the Eighth Amendment bans any punishment you can’t carry out without respecting the dignity of those being punished.”

Kennedy leaned heavily on the importance of dignity in Brown v. Plata, the California prison overcrowding case. Simon even found an early Kennedy opinion from when he was a circuit court judge in the 1970s in which he quoted Brennan’s concurrence in Furman at length.

Even if Kennedy doesn’t buy a dignity argument for abolishing the death penalty, Simon said he thought Kennedy would be swayed by the issue of delays, which Breyer raised in his 2015 anti-capital punishment dissent — and which were the entire reason for the prisoner’s stay in solitary confinement that Kennedy assailed in his concurrence last year.

”[Kennedy] came and gave a talk at Berkeley Law about a year and a half ago, and one of my colleagues was rude enough to ask him point blank whether he thought the death penalty was compatible with human dignity,” Simon told me. “Of course he declined to answer, but he said kind of cryptically, ‘Here in California you guys take so long enough to execute people that we may not even need to reach that cliff.’”

Even if Kennedy isn’t willing to go as far as abolishing capital punishment entirely, it’s likely that having him off the bench would prevent incremental steps against it from going forward. In 2008, Kennedy wrote for a 5-4 liberal majority that it was unconstitutional to impose the death penalty on people convicted merely of rape, not murder. Without him on the Court, incremental limitations of capital punishment’s scope like that become less likely.

Affirmative action in America after Kennedy

Anthony Kennedy is hardly an uncritical supporter of affirmative action in public employment, education admissions, or other realms.

In 2003, he dissented in Grutter v. Bollinger, a case where O’Connor and the Court’s liberals ruled that the University of Michigan Law School’s racial affirmative action system was constitutional, and not an unconstitutional quota system. In 2007’s Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1, he was the swing vote behind a ruling holding that Seattle, Washington, and Louisville, Kentucky’s voluntary desegregation programs were unconstitutional.

In 2009’s Ricci v. DeStefano, he ruled that New Haven, Connecticut’s Fire Department discriminated against white applicants for promotions. He wrote the controlling opinion in 2014’s Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action, which upheld Michigan’s ban on affirmative action.

But he is not an implacable foe of the practice, either. In his Grutter dissent, he echoed Justice Lewis Powell, who held Kennedy’s seat before him and wrote the controlling opinion in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, a 1978 case in which the Court held that affirmative action was constitutional but explicit quotas (“16 of the 100 students must be black”) went too far.

“There is no constitutional objection to the goal of considering race as one modest factor among many others to achieve diversity, but an educational institution must ensure, through sufficient procedures, that each applicant receives individual consideration and that race does not become a predominant factor in the admissions decision-making,” Kennedy wrote in the Grutter dissent.

This position of his became additionally relevant with 2016’s Fisher v. University of Texas, in which he wrote a majority opinion defending the University of Texas’s use of race in admissions. With Fisher, he effectively became the one vote holding together the Court’s majority defending affirmative action in at least some cases.

With Kennedy gone, replaced by a more stalwart conservative, it’s likely that the uneasy affirmative action consensus will buckle, and a ruling finally doing away with public affirmative action programs will come.

Gay rights in America after Kennedy

Arguably, Kennedy’s greatest legacy on the Court — and certainly what he hopes will be his greatest legacy — are his decisions expanding the scope of LGBTQ rights.

In 1996’s Romer v. Evans, he authored the Court’s first major pro-gay rights decision, invoking the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause in striking down a Colorado state constitutional amendment that prevented cities and towns from adopting their own bans on discrimination against gays, lesbians, or bisexuals.

Seven years later, in 2003’s Lawrence v. Texas, Kennedy wrote for a 6-3 court invalidating Texas’s ban on oral and anal sex between two men or two women. That decision overrode 1986’s Bowers v. Hardwick, a decision upholding Georgia’s sodomy law. In Lawrence, Kennedy tellingly did not use equal protection reasoning but instead found that any bans on consensual sexual behavior between adults, regardless of the genders involved, violate the due process clause’s guarantee of personal liberty. (This was similar to the reasoning the court had used in Roe and to invalidate bans on contraception in Griswold v. Connecticut.)

A decade later, in 2013, Kennedy wrote the 5-4 decision in United States v. Windsor overturning the federal Defense of Marriage Act on equal protection grounds. The decision required the federal government to respect and honor same-sex marriages at the state level, while still allowing states to ban same-sex marriage if they wished. And two years after that, in 2015’s Obergefell v. Hodges, he swept away bans on same-sex marriage altogether, ending with a stirring tribute to the value of marriage that’s become a mainstay of wedding readings in the years since:

It is fair, then, for gay rights advocates to worry about what could happen to the Obergefell precedent should Kennedy retire.

There are certainly some conservatives on the Court who are interested in chipping away at the ruling’s guarantees. Gorsuch, Thomas, and Alito in 2017 dissented from a ruling requiring Arkansas to list same-sex parents on their children’s birth certificates, arguing that to do so does not violate Obergefell. That, Slate’s Mark Joseph Stern argued, set the stage for a legal strategy based on gradually chipping away at the right to marriage until it’s practically worthless.

“[John] Roberts would be free to rewrite Windsor and Obergefell however he wants,” Stern writes. “Roberts could remain faithful to the original text of both decisions. He could also reverse them. But the likeliest possibility is that Roberts first cuts them down to a single guarantee—the right for same-sex couples to receive a marriage license with no attendant privileges. In case after case, Roberts could vote to allow discrimination against same-sex couples but affirm their right to the license itself.”

The trouble with this argument is that we don’t actually know where Roberts stands on the precedential value of Obergefell. He didn’t register a dissent in the Arkansas case the way his conservative colleagues did; it’s possible he dissented without letting that dissent be recorded but it’s also possible he sided with the liberals.

Moreover, majorities of Americans in 44 of the 50 states now support same-sex marriage. The overwhelming public opinion shift in favor of marriage equality might make Roberts more hesitant to chip away at the right, and it also might deny the Court opportunities to take up the issue, if the popularity of same-sex marriage prevents states from trying to restrict the right in ways that would be challenged and make it to the Court.

My hunch is that LGBTQ rights is the part of Kennedy’s legacy least likely to be sacrificed should he leave the Court. But certainly a Court without Kennedy, and with a Trump-appointed successor, will be less friendly to LGBTQ causes than a Court with him around.

Sourse: vox.com