Perhaps the most incredible scene in “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?,” the recent documentary about Mr. Rogers, features Mr. Rogers meeting Koko, the beloved western lowland gorilla. Koko, who died in her sleep this week, at forty-six, was known for her facility with American Sign Language, her emotional acuity, and her love of her pet kitten, All Ball. Koko was the world’s foremost celebrity gorilla. And she was, apparently, like so many sensitive souls of our generation, a Mr. Rogers fan. In the scene, Rogers visits Koko, and she embraces him; as they sit on the floor, she cradles him in her massive arms. It’s an astounding moment of interspecies affection, and one that makes intuitive sense. Koko seems to be doing for Mr. Rogers what he did for us: providing boundless love and care that we hadn’t sought but deeply craved. It’s the one time in Morgan Neville’s film when Rogers seems to be the child, the grateful recipient of something like parental love. His expression is one we haven’t seen on him before—gratitude, joy, awe, possibly a hint of fear, like a novice surfer riding a wave. Koko unties Rogers’s shoelaces and takes his sneakers off, just as she’d seen him do on TV.

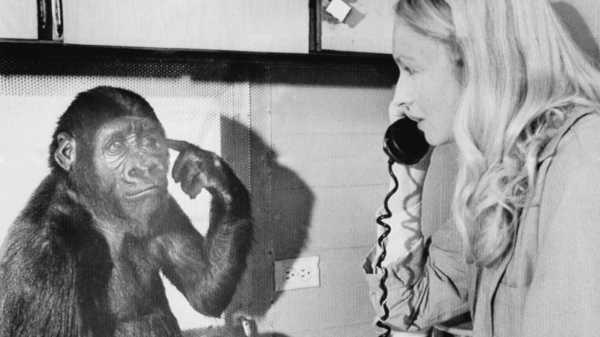

Koko, whose full name, Hanabi‐Ko, means Fireworks Child in Japanese, was born on July 4, 1971, at the San Francisco Zoo. Early in life, she began working with a young researcher named Francine (Penny) Patterson, then a doctoral student in psychology at Stanford University, who went on to work with Koko for much of her career. After three years of training, a Times piece from 1975 reported, Koko could correctly sign more than a hundred and seventy words. (Later, she could sign a thousand.) In that article, “Koko the Gorilla Gives Hints of Being Smarter Than the Chimpanzees,” Sandra Blakeslee wrote, “Koko falls three to six months behind human children in mental abilities for her age. Her perceptual-motor abilities (e.g. the ability to swing through trees) are, of course, far advanced.” Among her qualities that showed up the chimpanzees were inventiveness and wit.

Miss Patterson said that Koko uses language creatively. “She

occasionally makes up new words [signs] which are amazingly

appropriate and she is able to string known words together in novel

and meaningful constructions. Koko also has a sense of humor and plays

word games,” the trainer said.

The article reported that Koko had “a sand box, a wheelchair, a tricycle and a barn yard full of university‐owned laboratory animals out her front door,” and that she tried to communicate with neutered bulls in sign language; she seemed to exist in a kind of human-gorilla limbo. She broke toys “at a brisk pace,” liked to clean up spills but then tried to eat the sponge, was potty-trained but did not empty the potty after each use. Sometimes she played “quietly with Play‐Dough, Tinkertoys, paints, trucks and other small objects,” sometimes she bounded around her room, being boisterous and “very loud.” Aside from pestering neutered bulls, much of this was exactly how human kids her age were behaving.

I tried to explain to a younger cousin, a few months ago, what I referred to as “seventies primate culture,” which I felt was an important thing for him, a child of the eighties, to understand. Seventies primate culture was broad and deep, and Koko was its apex. Every generation loves apes, perhaps, but growing up in that shaggy era involved a heightened amount of imagined communing with gorillas, chimpanzees, orangutans, and snow monkeys. We had our unnerving spate of man-and-ape buddy comedies—trucker orangutans, trucker chimps, etc.—but, beyond that, pop culture and the scientific community popularized earnest, loving representations of primates of many kinds, many of which seemed to be verging on consciousness-expansion.

A 1970 cover of Life (“Ecology Becomes Everybody’s Issue”) featured a beleaguered-looking, pink-faced snow monkey enjoying a hot-springs bath in Japan. That fuzzy-headed humanoid, with snow on its fur and warmth in its bath, seemed to be all of us, somehow, and in the seventies and early eighties you’d see posters of it everywhere. One was in the music room at my school, and we stared at it as we sang songs and banged glockenspiels. Meanwhile, we’d hear about Jane Goodall, observing her chimpanzees in Tanzania year after year and discovering that they could use tools, and about Dian Fossey and “Gorillas in the Mist.” In many households, people talked about Harry Harlow’s famous midcentury studies of baby monkeys and wire or terry-cloth surrogate mothers, indicating that, like us, they craved a mother’s love.

My own mother and I were highly attuned to these discoveries; she had shelves full of books about life sciences, including many on primates, including Patterson’s “The Education of Koko,” from 1981. Koko seemed like an ambassador of all the love we felt for gorillas and our other thoughtful primate cousins. She seemed to provide valuable clues to the mystery of the essence of the hominid. Much of this, no doubt, was projection—but, rationally or not, we saw in Koko something that felt like a true bridging of the divide between man and ape, and in that, a deeper understanding of who we are, who primates are, and our collective role on this planet and in the scientific order.

My mother died many years ago, and in recent months I’ve been going through her books, exploring her consciousness. I’m currently reading one of them, “The Mind of an Ape,” by David and Ann J. Premack, about their studies of chimpanzees. A paragraph in its introduction seems to resonate beyond chimps, and to Koko:

Should we gaze at a monkey, it would reveal no inclination to exchange

glances; it would furtively avert its eyes, or enlarge them in a

hostile stare.… Apes and humans, in contrast, enjoy being the focus of

attention. Humans regard being looked at as an honor, as proof of

personal achievement. Far from averting its eyes, the chimpanzee

returns our gaze avidly. While looking at us, the chimpanzee appears

to be asking the very questions about us which we ask about it as we

gaze into its eyes.

This idea is reinforced by the cover image from a 1978 National Geographic, illustrating a feature story about Koko, “Conversations with a Gorilla.” She’s looking straight at the camera, peering through a 35-mm. camera that she holds, seeming to use a human tool to observe the photographer taking a picture of her. It is, in fact, a mirror, and a self-portrait.

I don’t know if other people associate Koko with motherly love, as I do, but because my own mother is gone, I especially appreciated Koko’s continued presence in our world, and had been thinking about it after seeing “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” That film is striking a chord among people in a nation in an ongoing state of anxiety verging on panic. Koko, who inspired the kind of affection that Mr. Rogers did, happened to die during a time when we crave reassurance, and during a week of an unfolding national crisis of state-sponsored parent-child separation of immigrants and refugees. The reality of the news keeps the death of a special gorilla in perspective. But it also plucks at the same tender emotions, the same primal bond that we feel between parent and child, and feelings of love and sadness together. Observing Koko’s empathy and her charming self-expression—“she referred to a zebra as a ‘white tiger,’ a Pinocchio doll as an ‘elephant baby,’ and a mask as an ‘eye hat,’ ” Patterson wrote—seemed to be like observing those qualities in a growing human child. Whatever we’re projecting, whatever our love of Koko meant about childhood and connection and care, that emotion and the bonds it stands for are vital to nurture and protect.

Sourse: newyorker.com