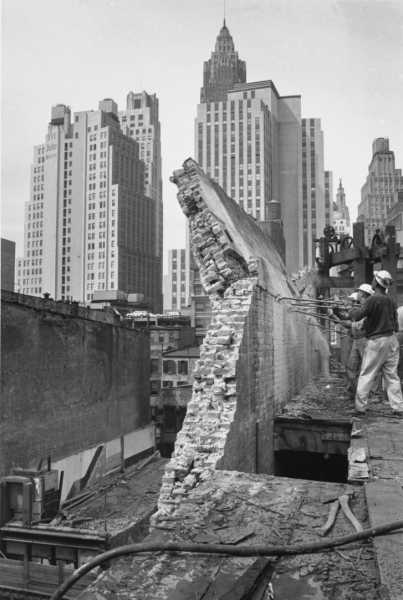

In 1966, after several years spent rambling around the country photographing a Chicago-based motorcycle club, Danny Lyon returned to his native New York City. Lyon had previously worked as the staff photographer for the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and when he moved into a downtown apartment on Beekman Street, at the age of twenty-five, he was already well on the way to making a name for himself. Beekman was dotted with boarded-up buildings. Lyon learned that the block was among the sixty acres below Canal Street slated for clearing, areas that had once been a hub of thriving printing and produce industries but had bled out economically after the Second World War. As Elisabeth Sussman notes in the catalogue for “Message to the Future,” a recent retrospective of Lyon’s work at the Whitney, powerful developers, like David Rockefeller and Robert Moses, saw potential profit in remaking these spaces. But when Lyon looked at them he saw “fossils,” traces of life dating back to before the Civil War. So, with funding from the The New York State Council on the Arts, he set out with a view camera, slipping in and out of demolition sites from the East River to the Hudson. In a project he titled “The Destruction of Lower Manhattan,” he photographed the folks leaving buildings and those tearing them down, and, in so doing, documented the social dismantling that buzzes under every project billed as urban renewal.

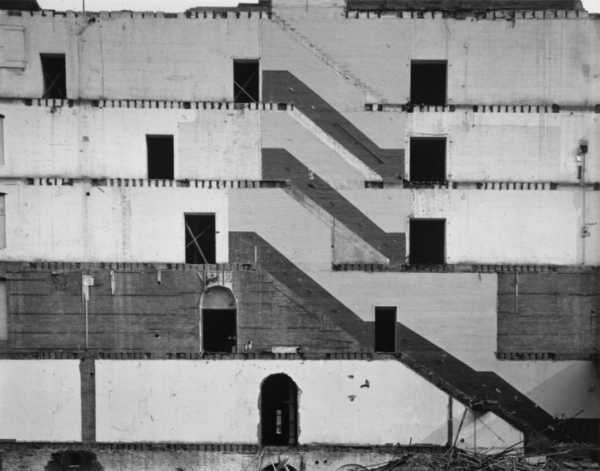

“327, 329, and 331 Washington Street, Between Jay and Harrison Streets.”

“Ben and His Brother Junior on the Walls.”

Many of Lyon’s images—which were collected in a book published in 1969, and are the subject of an exhibit opening this month at the Cleveland Museum of Art—have the formal qualities typical of survey photography. The lines run straight; light is generally even, not dramatic. His photographs from Chambers, Washington, and Cliff Streets show dormers and awnings carefully arranged in the frame. But as soon as your eye assumes that it is looking at a straightforward architectural subject, crowbars start toppling buildings, demolition workers emerge from rubble like shapes from a Magic Eye, and a man in a hard hat steps out through a hole in a painted brick wall, as if emerging from a portal. Lyon’s empathy is quiet but ever present; his images heighten our awareness of the human history layered under every pile of rubble in the city.

“Dropping a Wall.”

“A Burner Is Lifted to Cut the Bolts in the Cast-Iron Front of 82 Beekman Street. The Cast Iron Is Then Smashed to Pieces with a Sledgehammer.”

“Housewreckers at Lunch on the West Side.”

While navigating demolition sites, Lyon would search a surveyor’s map both to orient himself and to caption his photos with precise locations. Reading about this process, I was reminded of “Surveyor,” the crowd-sourcing project, launched last year by the New York Public Library to geotag all of the photographs in its digital collections. Visitors to the “Surveyor” Web site are prompted with random photographs from the archive and asked to plot them onto a map of New York City, relying on landmarks or drawing on historical knowledge to identity spaces that have changed or disappeared since the photograph was taken. It is easy to imagine encountering photographs from Lyon’s project on “Surveyor,” and worth asking which ones we could place. Take the photograph from the remains of the Tribune Building, which once stood where Pace University’s main building does today. In the foreground, we see the exposed I-beams and debris of a building that has already started to vanish. But there, framed off to the right, are the peaks of the Brooklyn Bridge—we know at least that we are downtown, looking East. Or, if you don’t recognize the exact buildings and streets in Lyon’s photograph of the intersection of Washington and Murray, maybe you could consider how cobblestones and iron awnings like those in the picture have been preserved to peddle the charm of condominiums in modern-day TriBeCa.

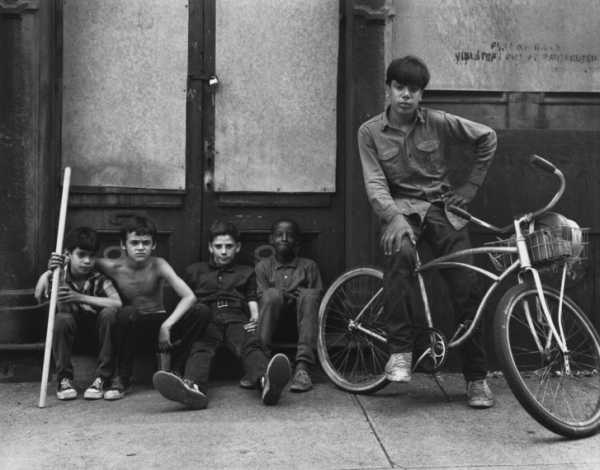

“Beekman Street, Sunday Morning; Ginco, Tonto, Frankie, John Jr., and Nelson, After Exploring the Buildings.”

Harder to pinpoint are Eddie Grant and Cleveland Sims, two maintenance men in another of Lyon’s photographs. They are holding a broom and a rake, respectively, and wearing uniforms bearing “Urban Renewal Service Man” patches. There is an address on the door behind them—286—but from the building’s peeling paint and shoddy frames we can guess it is one that has since been demolished. We sense Lyon’s concern, especially, in images like this one. By mixing portraits among his survey photographs, he questions whether a process capable of restructuring at this scale could possibly reserve consideration for individuals like Grant and Sims, or the kids he sees on his block on Sunday morning, or the men disappearing into rubble while clearing lots. Lyon has said that, at the time, he was surprised by how little the newspapers had to say about this massive transformation. The appeal he makes in “Destruction” is simple: all he wants is for us to notice what will soon be gone.

“Eddie Grant and Cleveland Sims. Washington Street Maintenance Men from the New York City Department of Urban Renewal.”

“View South on Cliff Street at its Intersection With Beekman.”

“The Ruins of 100 Gold Street.”

“258 Washington Street at the Northwest Corner of Murray Street.”

“View South from 88 Gold Street.”

“100 Gold Street Seen from the Remains of the Tribune Building.”

“View Through the Rear Wall, 89 Beekman Street.”

“88 Gold Street.”

“Portrait of a Young Man in an Abandoned Room.”

“Marilyn, in an Abandoned Building.”

“Wall of the St. George Building.”

“Brick Crew on the West Side. Bricks Are Salvaged and Sold as Antique Brick for Use in New Homes.”

Sourse: newyorker.com