I went to the circus at Madison Square Garden when I was about six years old, and, afterward, through some forgotten benefactor, I was taken backstage. There were clowns strolling around in their costumes, but they were talking normally, out of character. The man on stilts was walking on his own two feet, carrying the stilts. The lions were in their cages. It was the first time I saw, and understood, the backstage world that made the spotlit world possible.

The next time I regularly entered this backstage was while working as a stringer for U.P.I., a wire service for whom I covered several of the less desirable Knicks games, in the spring of 1988. It was Rick Pitino’s first season as the Knicks’ coach. Patrick Ewing and Mark Jackson were the stars of the team. I was fascinated to glimpse Ewing in person—stoic and furiously silent at his locker, his knees enclosed in ice packs; intrigued by Pitino’s boyish, fresh-faced eagerness. But the most lasting image from those first forays into the backstage world of the N.B.A. occurred in the visitors’ locker room.

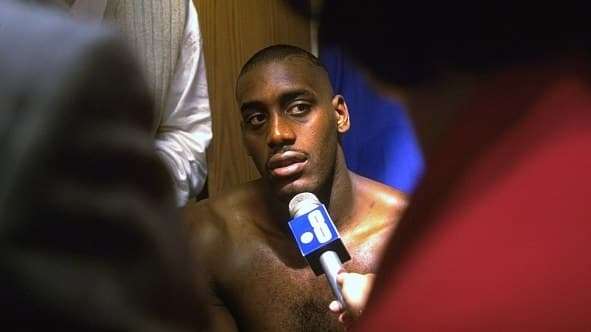

The Knicks had played the Cavaliers. A mob of reporters and television cameras bristling with microphones and tape recorders surrounded the Cavaliers’ young star Ron Harper, who sat in front of his locker. Harper’s face and bare shoulders were bathed in the bright white light of a television camera while he spoke. At first I could only see the top of his shaved head. When I got closer I was amazed to see that he was entirely nude. The white light framed what people could see on TV. But outside the frame, there was more to see.

These days I watch N.B.A. games in New Orleans. Being in the stands of the Smoothie King Arena is different from the stands at Madison Square Garden, but backstage, these arenas are all similar. And, as with grand museums, one moves through them faintly wondering what it would be like to stay late, past closing, and be a stowaway.

The Pelicans’ first home game of the season, on October 20th, was a loss to the Golden State Warriors. Afterward, I went to the Warriors’ locker room. Smartphones, social media, and a co-ed workforce have made locker rooms a more circumspect space. Stephen Curry, shirtless with a towel around his waist, sat with his knees wrapped in ice packs so large that they looked like pillows. He perched as though on a throne, each foot propped on a chair, in a seance with his phone. Klay Thompson, Kevin Durant, and other Warriors were in various stages of molting back into civilian life, talking among themselves or to clusters of journalists who flitted in a group among the lockers. I approached the veteran David West, who was seemingly in no rush to change, asked him some questions, and then turned to see Shaun Livingston.

For anyone who has been watching N.B.A. basketball for a while, Livingston is an incredible story, a player who has become an essential supporting actor on the league’s dynastic team and who has somehow transcended what had seemed sure to be his legacy—an awful injury on live television, his leg buckling the wrong way at the knee. That he was such a long, spindly player made it all the more vivid and terrible, a brittle twig that snapped. Yet for me, the indelible image of Livingston occurred not on the court but in the locker room, a couple of seasons ago, when I happened to walk past the open door of the visitors’ locker room just as he was standing at a buffet of food and scooping some into a styrofoam shell. One often hears about a kind of science-oriented culinary extravagance when it comes to nutrition and N.B.A. stars—Rajon Rondo’s season was apparently revived when his personal chef devised a new milkshake recipe—but the visiting-team buffet looked, at that moment, to be that of a middling Chinese restaurant, at best. The styrofoam shell only added to that impression. But Livingston was hungry, and scooped the food with a look of blank anticipation that for some reason has stayed with me; he was clearly going to be eating it on a bus, or a plane. I saw all this in the time it takes for a door to close.

Players are also required to speak briefly to the media before games, after which they can return to the locker room or stay on the court and work on their game, usually with a coach or two in attendance to rebound. I like this time the best. I stand on the baseline watching the workout with the intensity of a scout. Before Game 3 of the Pelicans–Trail Blazers playoff series, Rondo put up about sixty three-point shots from the same spot, holding his hieroglyphic hand in a definition of a gooseneck follow-through every time, while at the far end of the court, on the other basket, Al-Farouq Aminu, the former Pelican, practiced his three-point shot, with his distinctive pointed-elbow release, the two of them moving in an entirely autonomous rhythm that was somehow metronomic and connected, like oil derricks pumping in the same field.

When the Pelicans are introduced, it gets very loud, dark, and pyrotechnic. I stand near the visiting team at this moment. Flamethrowers start erupting from atop the backboards, and each Pelican player comes out to cheers, the loudest saved for last, Anthony Davis. Every arena now has some version of this ritual. While the crowd is cheering and the place is becoming as smoky as a seventies rock concert, the visiting team’s players jog in place, huddle together, or sit quietly alone. They almost seem to be savoring this brief, private interval when they are anonymous and invisible amid the noise and chaos. For some reason, the bench players often jump up and hang from the rims at this time, perhaps because it’s their last chance to touch the hoop before taking a seat on the bench. Their bodies rise up, dangle from the rim for a few seconds, and then drop down, a visual effect that only adds to the disturbing, fog-of-war feeling of this interlude.

Before and after games, I wander the hallways in a slow-motion act of loitering, and the supremely gracious ushers of the Smoothie King Arena, all outfitted in mustard-colored jackets, will politely move me along when I stay too long in one place. The hallways are both intimate scenes, where everyone there has gone through security and has a reason to be there, and also as anonymous as the sidewalk of a crowded city street. People look straight ahead, attending to their own pressing business, except when they don’t. You never know from whom you will get a nod.

All sorts of people are moving up and down these halls —cheerleaders (both the young version and the senior version), the halftime entertainment, N.B.A. officials, coaches, players. Certain images linger from these occasional forays, such as Paul Pierce and Kevin Garnett, back when they both played for the Nets, coming up the tunnel toward the court at halftime, huge black curtains draping them on either side, the two players laughing and bumping into each other, delighting at some shared joke. Perhaps the joke of the single season they played for the Nets.

After all the locker-room interviews are over and the press has filed out and retreated to the press room, the only people left are equipment managers, players, and those congregated in the family room. People start to spill out into the hallway. There is a sense of informality, relaxation, a party. Once I saw two men in suits eating from a box of large, ripe, chocolate-covered strawberries. They saw me looking as I strolled by.

“You want one?” one of the men said.

“You sure?”

“Go ahead,” the guy with the box said.

I stood with my two new friends, who turned out to be veteran N.B.A. employees who wished not to be identified. They were involved with the refereeing at games. From them I learned about R.S.B.Q., the four tenets of basketball refereeing: rhythm, speed, balance, quickness. “A foul is committed when one of these principles has been compromised by contact with another player,” one of the men said as I bit into a chocolate-covered strawberry.

I have a vivid memory of seeing Vince Carter on another late night, walking onto the team bus after a game, going to what I was told was his usual seat in the back. He leaned his head against the window, headphones on, and peered out into the darkness as though he had just boarded the late bus home from school.

After a Pelicans game against the Thunder last fall, I went to the press room and wrote for a while, stared at the stat sheet, stared at the wall, and then went for another walk. Russell Westbrook, now in street clothes—white sweatshirt, pale jeans, high tops—looked like a high-school jock from my own years in high school, in the nineteen-eighties. He stood in the hall talking to people, in no hurry to go anywhere, seeming to enjoy the passing parade. One of the Pelicans’ towel boys came by with some takeout boxes, and offered Russell a cookie. He took it. “I’m always the last one to go,” he said, to no one in particular, yet, somehow, surrounded by people, everyone lit up at the sight of him. “I stay late.”

But I stayed later. The press room was empty when I finally left. So was the whole arena, it seemed. I took one last stroll and found myself at the now unguarded door of the visitors’ locker room. I stepped inside and stood there for a while. The locker room was empty of Westbrook and Carmelo Anthony and Paul George and the rest of the Thunder, but it was otherwise unchanged, the debris of tape and empty water bottles strewn on the floor like the silhouette of the circus that had been to town and moved on.

Sourse: newyorker.com