Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

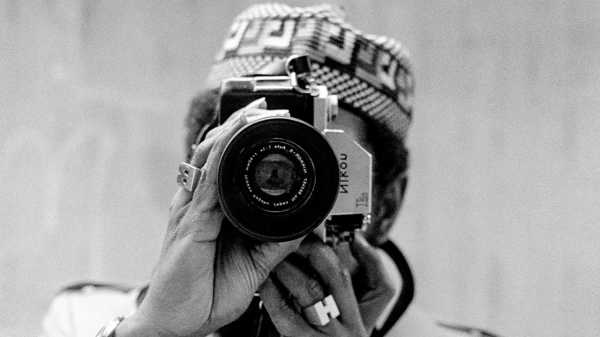

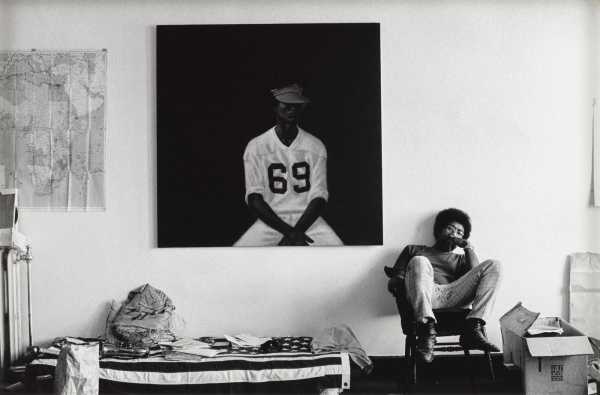

The artist Barkley L. Hendricks was known during his lifetime, though not nearly well enough, for his swaggering portrait paintings. During travels in Europe as a young man, Hendricks had been struck by the absence of Black folks like him in the works of the Old Masters he admired. In paintings like “Lawdy Mama” (1969), showing a woman with a voluminous Afro against a gold-leaf, Byzantine-style background, Hendricks sought to redress this historical omission and make icons for a new era. Many of his subjects were people he knew, or encountered on the street. Often, he’d take their picture and then go about conjuring his subjects on canvas, isolating them against monochromatic backgrounds to allow their style and spirit to shine through unencumbered. He called his camera “my mechanical sketchbook,” though that description is perhaps too modest. Certainly, some of his pictures were merely the raw material out of which his paintings were made. A picture from 1973 of his friend and sometimes muse George Jules Taylor looking pensive in a wide-brimmed hat, for instance, was spiked with a touch of confrontational attitude when it was transformed the same year into a painting, “New Orleans Niggah.” But a trove of photographic work discovered after Hendricks’s death, in 2017—a selection of which is currently on view at Jack Shainman Gallery, in New York—makes the case that Hendricks was a photographer in his own right when he was so inclined.

“Untitled,” c. 1980.

“Untitled,” c. 1980.

Hendricks had been toting around a camera since his adolescence in North Philadelphia. However, he gained admission to the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts for his skills as a draftsman. Before attending Yale, in the early seventies, where he ultimately received both bachelor’s and master’s degrees, Hendricks made brilliant, quasi-minimalist paintings of basketball hoops and court markings which call to mind the work of both Josef Albers and Ad Reinhardt. But his main love was portraiture, an affinity that put him out of step with the heady abstraction that ruled the Yale art department at the time. This incompatibility drew him to study photography, under the tutelage of Walker Evans. Evans’s influence can be seen here and there in Hendricks’s photography—a picture of a wall of clocks in an antique store, taken while Hendricks was at Yale, could be an Evans outtake—but in photography, as in art, Hendricks was guided by his own passions. Like the seminal hip-hop-style sleuth Jamel Shabazz, Hendricks had a reverence for the attention-grabbing theatrics of urban street style. In one picture, taken on a trip to Nigeria in 1978, a man in a spotless, hot-pink ensemble and a patterned hat stands with one arm jauntily akimbo, in front of a waterlogged agglomeration of creaky shacks, a blazing figure of defiance amid his dour surroundings. In another, from 1983, a man in a white mesh T-shirt, flared jeans, and artfully scuffed white sneakers carries a gleaming boom box by a shoulder strap, broadcasting both his personal style and his musical tastes to the world. Fashion, Hendricks knew, was not simply a way to live loudly. When he heard Bobby Seale, the co-founder of the Black Panther Party, remark that “Superman never saved any Black people,” he bought a Superman T-shirt, and posed in it for a photographic self-portrait—sans pants. The picture, which Hendricks transformed, later that year, into one of his better-known paintings, smolders with a contemptuous irony but also an unmistakable pride, as if to say, “Who’s Superman now?”

Like the subjects of his paintings and his street pictures, Hendricks loved to peacock for the camera. In another self-portrait, from 1980, he wears a white dress shirt and woven tie underneath a V-neck sweater whose bright-red color matches his futuristic, wraparound sunglasses. The ensemble is part prep school and part P-Funk. A wistful self-portrait from the same year finds Hendricks in his home studio, wearing a white shirt and snappy black fedora, his right hand resting on his chest. Like Dürer in his Christlike self-portrait, or the regal Velázquez in “Las Meninas,” Hendricks here is both the self-assured master and the dandy who likes to recall the time his sister remarked, “You think you’re slick, just wait, one day a woman is going to straighten you out.” (A painted riposte entitled “Slick (Self Portrait)” suggests that he wore the label like a badge of honor.)

“Untitled,” 1979.

“Untitled,” 1992.

“Untitled,” c. 1970.

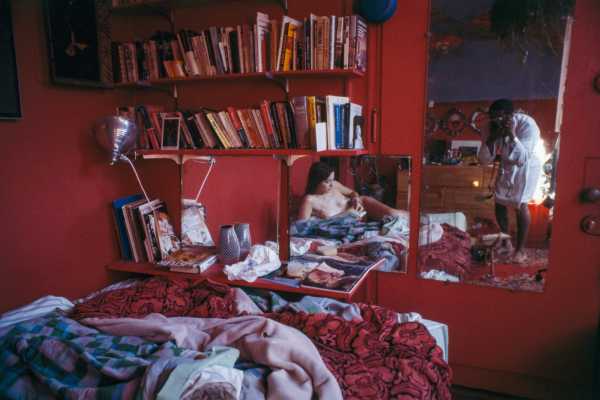

Speaking of clothing, and women, a discussion of Hendricks’s photography would not be complete without mention of women’s shoes. Hendricks had an affinity for them and, yes, for feet, too, to the extent that many of his pictures seem almost like fetish fare, bringing to mind the work of the famously foot-fixated photographer Elmer Batters. Hendricks’s pics are perhaps a bit pervy, but they are also quite playful: a pair of heels rests incongruously on the Great Wall of China; a stockinged foot belonging to his wife, Susan, rests beside her empty shoe, in a work entitled “My Honey’s Tootsie,” so that she seems for a moment to have three feet. Other works in this vein are elegant, like a 1980 photograph of a woman adjusting her stockings; or the 1975 picture of an alluring pair of legs, shod in a pair of dark heels, reflected in what appears to be not so much a mirror as a portal to a fantasy world.

“Untitled,” c. 1980.

“Untitled,” 1991.

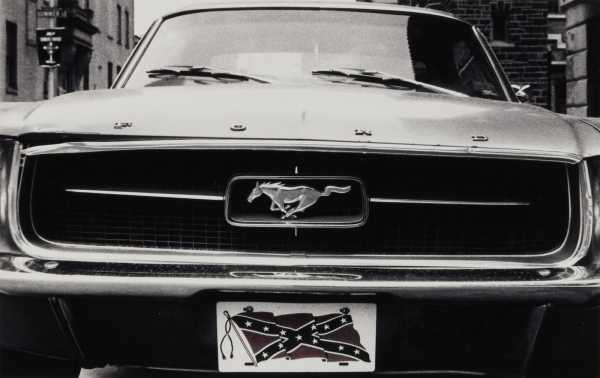

Hendricks’s interests were wide-ranging, to say the least, and he insisted that his paintings, like his pictures, were not expressly political. “My paintings were about people that were part of my life,” he said, in an interview with the Brooklyn Rail a year before his death. “If they were political, it’s because they were a reflection of the culture we were drowning in.” But in his photographs Hendricks could sometimes wear his politics on his sleeve. Some of his most blatantly political photographs were of cars, which he pictured as repositories of American dreams and stand-ins for their drivers. His picture of the front of a Ford Mustang, taken in 1971, draws a parallel between the car’s majestic, macho logo and a decorative Confederate-flag license plate affixed to the bumper. In what could be a pendant piece, taken in 1982, we see a rusting, bashed-up car held together by a length of chain and featuring a similar Confederate-flag plate, suggesting an owner with a spurious sense of superiority. Two other cars, one photographed in 1970 and the other in 1975, show, respectively, a poster of Martin Luther King, Jr., taped up in the back window and a cutout of Abraham Lincoln that makes it look as if the former President is riding along; the pictures within the pictures appear like messengers of hope. A photograph that he took while posing as a journalist at a rally for the Ku Klux Klan held in 1982 in Norwich, Connecticut, along with a photo taken of a television set while it was airing footage of Rodney King being beaten by police officers, show us an American racism that is as ingrained as gravel in a tire tread.

“Untitled (Ford car with Confederate license plate),” c. 1971.

“Untitled,” c. 1995.

Perhaps Hendricks’s greatest joy as a photographer was the chance to take pictures of jazz and soul greats like Dexter Gordon, Julian (Cannonball) Adderley, and Ray Charles. He photographed the Afrobeat pioneer Fela Kuti at four separate concerts, and later made Kuti the subject of his 2002 altarpiece-like mixed-media work “Fela: Amen, Amen, Amen, Amen . . .” One can sense in Hendricks’s portraits of musicians not only his love of their art but also his admiration for their vibrant, audacious physical auras; their relationship with the world and with creativity was a quality that he recognized in himself. In an essay that Hendricks wrote for the catalogue of a long-overdue historic retrospective of his work, at the Nasher Museum of Art, at Duke University, in 2008, he recalled photographing Miles Davis backstage at a jazz festival in Canandaigua in 1988, and slipping Davis a catalogue of his paintings. “[I] told him I painted as well as he played, and he painted as well as I played the trumpet,” Hendricks recalled. “Miles smiled. How cool was that?”

Sourse: newyorker.com