A mass shooting near Margaret River, Australia, in the small village of Osmington, left a family of seven, including four children, dead. It’s the worst mass shooting in Australia since 1996, when a gunman in Port Arthur killed 35 people and wounded 23 others at a cafe.

Police found the family dead of gunshot wounds on Friday. Police have not confirmed whether the shooting was a murder-suicide, according to the Associated Press, but the authorities are not looking for a suspect.

The shooting has drawn attention in the US because Australia is often touted in America as a success story for gun control. Conservatives on social media quickly pointed to the mass shooting as evidence gun control does not work.

In an article for the Washington Examiner headlined “Despite gun control, Australia suffers worst mass shooting since 1996,” Siraj Hashmi wrote that “while some data suggest that super-strict gun control has cut down on gun violence and gun-related deaths in some cases, there’s still no guarantee that you’re safe.”

Hashmi’s conclusion is basically correct: Gun control can help, but it can’t stop every single shooting. It’s important to not get carried away here: Given that the research is pretty clear that gun control can make a big difference, this kind of mass shooting does not mean, as many people suggested on social media, that Australia’s stricter gun laws are futile.

The research is clear: gun control works

In 1996, a 28-year-old man walked into a cafe in Port Arthur, Australia, ate lunch, pulled a semiautomatic rifle out of his bag, and opened fire on the crowd, killing 35 people and wounding 23 more. It was the worst mass shooting in Australia’s history.

Australian lawmakers responded with legislation that, among other provisions, banned certain types of firearms, such as automatic and semiautomatic rifles and shotguns. The Australian government confiscated 650,000 of these guns through a mandatory buyback program, in which it purchased firearms from gun owners. It established a registry of all guns owned in the country and required a permit for all new firearm purchases. (This is much further than bills typically proposed in the US, which almost never make a serious attempt to immediately reduce the number of guns in the country.)

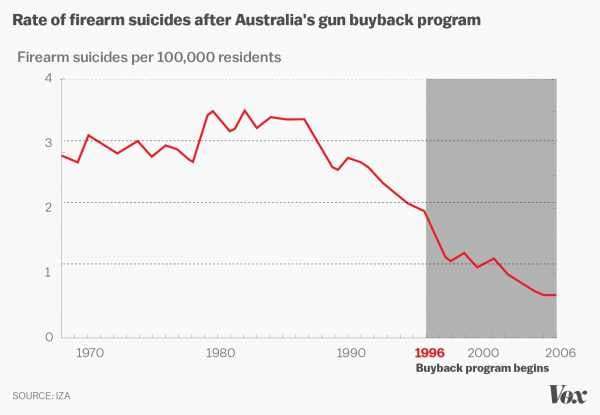

Australia’s firearm homicide rate dropped by about 42 percent in the seven years after the law passed, and its firearm suicide rate fell by 57 percent, according to a review of the evidence by Harvard researchers.

It’s difficult to know for sure how much of the drop in homicides and suicides was caused specifically by the gun buyback program and other legal changes. Australia’s gun deaths, for one, were already declining before the law passed. But researchers David Hemenway and Mary Vriniotis argue that the gun buyback program very likely played a role: “First, the drop in firearm deaths was largest among the type of firearms most affected by the buyback. Second, firearm deaths in states with higher buyback rates per capita fell proportionately more than in states with lower buyback rates.”

One study of the program, by Australian researchers, found that buying back 3,500 guns per 100,000 people correlated with up to a 50 percent drop in firearm homicides and a 74 percent drop in gun suicides. As Matthews explained, the drop in homicides wasn’t statistically significant because Australia already had a pretty low number of murders. But the drop in suicides most definitely was — and the results are striking.

One other fact, noted by Hemenway and Vriniotis in 2011: “While 13 gun massacres (the killing of 4 or more people at one time) occurred in Australia in the 18 years before the [Australia gun control law], resulting in more than one hundred deaths, in the 14 following years (and up to the present), there were no gun massacres.”

Other research backs this up. A 2016 review of 130 studies in 10 countries, published in Epidemiologic Reviews, found that new legal restrictions on owning and purchasing guns tended to be followed by a drop in gun violence — a strong indicator that restricting access to firearms can save lives. The review suggested that no one policy seems to have a big effect by itself, but a collection of gun restrictions can produce a significant effect over time.

This has held up in the US. Connecticut’s law requiring handgun purchasers to first pass a background check and obtain a license, for example, was followed by a 40 percent drop in gun homicides and a 15 percent reduction in gun suicides. Similar results — in the reverse — were reported in Missouri when it repealed its own permit-to-purchase law. It’s difficult to separate these changes from long-term trends (especially since gun homicides have generally been on the decline for decades now), but a review of the US evidence by RAND linked milder gun control measures, including background checks, to reduced injuries and deaths — and that means these measures likely saved lives.

The fundamental problem in the US: more guns, more gun deaths

The research helps explain why America has a gun problem unlike its developed peers. By having fairly lax gun laws, the US has allowed civilians to accumulate an abundance of guns for decades — and the result is more gun violence.

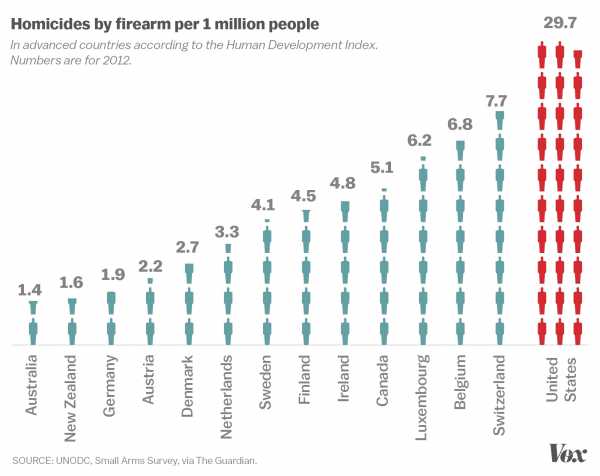

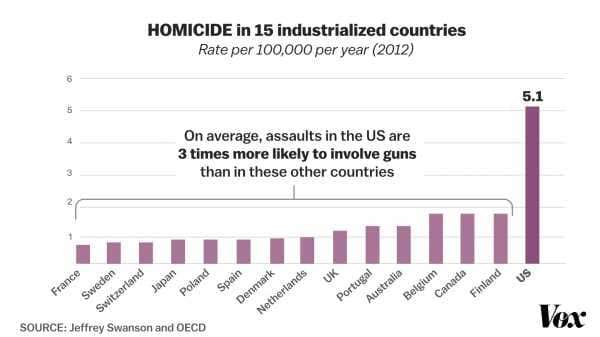

The US has nearly six times the gun homicide rate of Canada, more than seven times that of Sweden, and nearly 16 times that of Germany, according to United Nations data compiled by the Guardian. (These gun deaths are a big reason America has a much higher overall homicide rate, which includes non-gun deaths, than other developed nations.)

Mass shootings actually make up a small fraction of America’s gun deaths, constituting less than 2 percent of such deaths in 2013. But America does see a lot of these horrific events: According to CNN, “The US makes up less than 5% of the world’s population, but holds 31% of global mass shooters.”

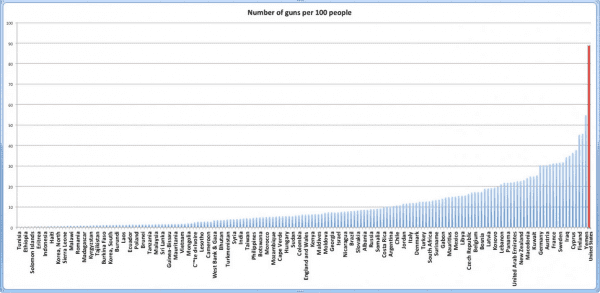

The US also has by far the highest number of privately owned guns in the world. Estimated in 2007, the number of civilian-owned firearms in the US was 88.8 guns per 100 people, meaning there was almost one privately owned gun per American and more than one per American adult. The world’s second-ranked country was Yemen, a quasi-failed state torn by civil war, where there were 54.8 guns per 100 people.

Another way of looking at that: Americans make up less than 5 percent of the world’s population yet own roughly 42 percent of all the world’s privately held firearms.

These two facts — on gun deaths and firearm ownership — are related. The research, compiled by the Harvard School of Public Health’s Injury Control Research Center, is pretty clear: After controlling for variables such as socioeconomic factors and other crime, places with more guns have more gun deaths. Researchers have found this to be true not just with homicides, but also with suicides (which in recent years were around 60 percent of US gun deaths), domestic violence, and even violence against police.

For example, a 2013 study, led by a Boston University School of Public Health researcher, found that, after controlling for multiple variables, each percentage point increase in gun ownership correlated with a roughly 0.9 percent rise in the firearm homicide rate.

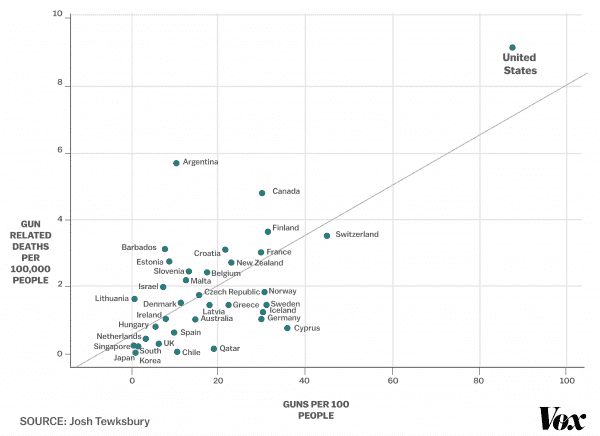

This chart, based on data compiled by researcher Josh Tewksbury, shows the correlation between the number of guns and gun deaths (including homicides and suicides) among wealthier nations:

Guns are not the only contributor to violence. (Other factors include, for example, poverty, urbanization, and alcohol consumption.) But when researchers control for other confounding variables, they have found time and time again that America’s high levels of gun ownership are a major reason the US is so much worse in terms of gun violence than its developed peers.

The logic, however, is simple: People of every country get into arguments and fights with friends, family, and peers. But in the US, it’s much more likely that someone will get angry at an argument and be able to pull out a gun and kill someone.

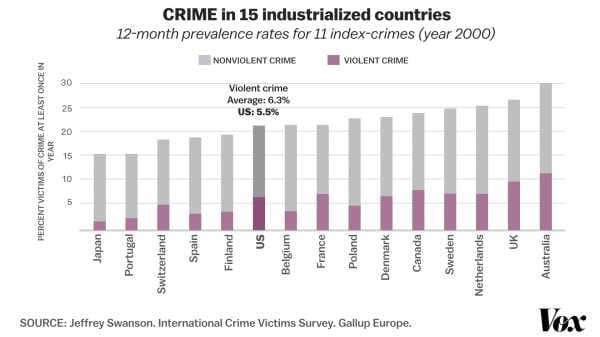

Other research has backed this up. As a breakthrough analysis by UC Berkeley’s Franklin Zimring and Gordon Hawkins in the 1990s found, it’s not even that the US has more crime than other developed countries. This chart, based on data from Jeffrey Swanson at Duke University, shows that the US is not an outlier when it comes to overall crime:

Instead, the US appears to have more lethal violence — and that’s driven in large part by the prevalence of guns.

”A series of specific comparisons of the death rates from property crime and assault in New York City and London show how enormous differences in death risk can be explained even while general patterns are similar,” Zimring and Hawkins wrote. “A preference for crimes of personal force and the willingness and ability to use guns in robbery make similar levels of property crime 54 times as deadly in New York City as in London.”

This helps explain why a mass shooting can still happen in places like Australia, despite strict gun laws. The country put new restrictions on guns and pulled some of them out of circulation, but it didn’t vanquish firearms entirely. And as long as some guns are around, it’s going to be possible for someone to pick up a firearm and carry out a massacre.

Sourse: vox.com