“I said I’d never marry anybody from my home town or anybody I met in a bar, and I did both,” the photographer Michael Northrup told me recently. “She pinched my butt, and that was that.” It was 1976. The home town was Marietta, Ohio, where Northrup was kicking around after finishing his B.F.A. at Ohio University, in Athens. “She” was Pam, a nurse. Northrup began photographing her right away, honing his style with the help of his new muse. When you live with a photographer, the line between artist and paparazzo can feel thin. But, as is made clear by “Dream Away,” Northrup’s new book of photos taken over the course of their relationship, Pam liked to pose for him. One early picture shows her lounging nude on a rough wooden bench, arranged against a patterned pillow like Ingres’s Odalisque or Manet’s Olympia, though Northrup often preferred to capture her in more spontaneous moments. The couple married in 1977, in San Francisco, where Northrup was continuing his photography studies. Right before they went to the courthouse, he snapped a picture of Pam sitting on the toilet in their small bathroom, her satin wedding dress bunched up around her knees, a box of kitty litter in the corner. It may not be a traditional portrait of a bride, but it is an honest one.

January, 1977.

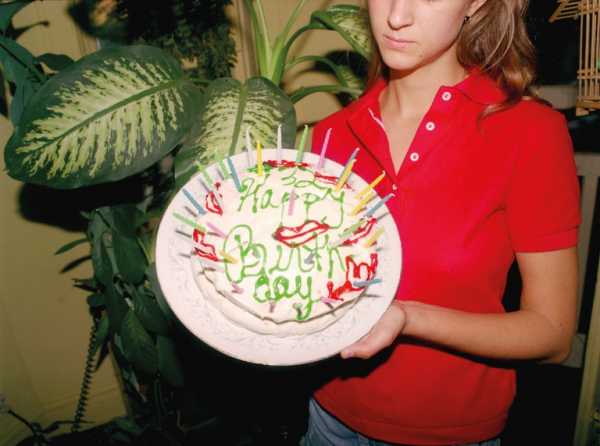

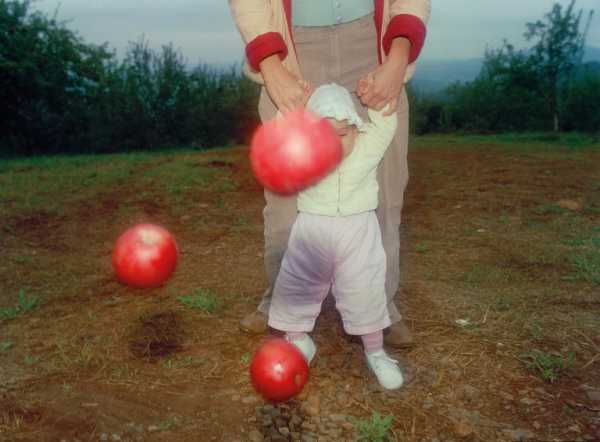

That tone of playful intimacy is characteristic of “Dream Away.” Northrup was influenced by the snapshot aesthetic, the photography movement, begun in the sixties, that prized everyday subject matter and a casual, amateur-seeming style of framing over highly formal compositions, and much of “Dream Away” has the private feel of a personal photo album. We see Pam at the height of pregnancy, her blue bathrobe carefully opened, like a purse, to reveal her full belly and a shock of ginger pubic hair. When we meet the couple’s daughter, she appears as a set of dimpled, pudgy legs thrown over her exhausted mother’s shoulder—a cherub who hasn’t quite learned to fly.

May, 1977.

August, 1977.

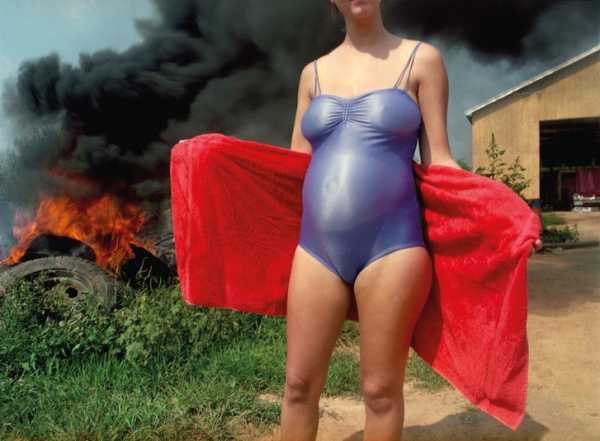

But if the book is an elliptical chronicle of a romance as it morphs into family, it also tells the story of Northrup’s development as a photographer. He loves visual rhymes and coincidences; he is always experimenting with new tricks and whims of composition. Take a look at his photograph of Pam by a tower viewer, her hair flying up in the wind, the features of her face echoed by those of the machine next to her; or of the one of her in the couple’s kitchen, holding aloft a chicken carcass by its picked-over legs as if teaching it how to dance. Northrup tries out black-and-white and then turns to saturated color, as in the photo of a very pregnant Pam standing in front of a red towel in a purple bathing suit, its fabric pulled tight over her belly like a Mylar balloon, as a tire fire a few feet away sends up an ominous pillar of smoke. The picture, dramatic and mysterious, seems almost narrative, though the story remains just out of the frame. The couple divorced in 1988, after more than a decade together. “Those moments are gone,” Northrup said. “It’s almost like I was this other person back then, and I stand here now, looking at this third party who took the photos.” In a sense, he has traded places with the viewer, who, coming fresh to these old pictures, encounters a long-vanished relationship for the first time.

August, 1977.

August, 1977.

August, 1977.

July, 1978.

September, 1978.

February, 1979.

May, 1979.

July, 1979.

August, 1979.

February, 1980.

August, 1980.

October, 1980.

January, 1981.

January, 1981.

September, 1981.

July, 1984.

September, 1984.

Sourse: newyorker.com