WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court ruled Thursday that the 2016 publication of an Andy Warhol image of the singer Prince violated a photographer's copyright, a decision a dissenting justice said would stifle the creation of art.

The high court ruled 7-2 for photographer Lynn Goldsmith. “Lynn Goldsmith’s original works, like those of other photographers, are entitled to copyright protection, even against famous artists,” Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote in the opinion for the court.

In a dissent, Justice Elena Kagan warned that the decision would "stifle creativity of every sort" and suggested the majority needed to “go back to school” for an Art History 101 refresher course.

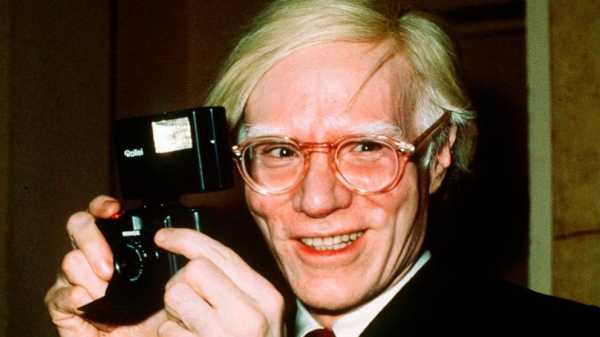

The case involved images Warhol created of Prince as part of a 1984 commission for Vanity Fair. Warhol used one of Goldsmith's photos as a starting point, a so-called artist reference, and Vanity Fair paid Goldsmith to license the photo. Warhol then created a series of images in his signature bright-colored and bold style.

Vanity Fair chose one of the resulting images — Prince with a purple face — to run in the magazine. Following Prince's death in 2016 Vanity Fair ran a different image from the series on its cover — Prince with an orange face. It was that second use that the justices dealt with in the case.

Lawyers for Warhol’s foundation had argued that the artist had transformed the photograph and there was no violation of copyright law when the orange-faced Prince was reproduced in the magazine. But a majority of the justices said a lower court had correctly sided with Goldsmith in this instance.

Sotomayor said the court was expressing no opinion “as to the creation, display, or sale of any of the original” Warhol works and whether they'd be seen as copyright infringement. “The same copying may be fair when used for one purpose but not another,” she wrote.

In a dissent, Kagan asked, "If Warhol does not get credit for transformative copying, who will?” She was joined in her dissent by Chief Justice John Roberts.

Kagan wrote that the majority's decision would “impede new art and music and literature” and “thwart the expression of new ideas and the attainment of new knowledge.” “It will make our world poorer,” she concluded.

Kagan said the visual arts has a tradition of imitation and copying. As one example she cited paintings by the artist Giorgione and his pupil Titian, including images of a reclining nude by each. The images were some of more than a dozen in the decision, unusual for a high court opinion. Images occasionally appear in opinions, particularly in art cases, but this time the color was particularly helpful. Without it, the purple-faced and orange-faced versions of the Prince images would look the same.

Goldsmith's original photo is black and white. Vanity Fair paid her $400 to license it for Warhol's use, and Warhol used it to create 16 works: two pencil drawings and 14 silkscreen prints. The silkscreens are done in the same style he had used to create well-known portraits of Marilyn Monroe, Jacqueline Kennedy and Mao Zedong. He cropped Goldsmith's image, resized it and changed the tones and lighting. Then he added bright colors and hand-drawn outlines.

Vanity Fair ran just one of the images Warhol created, the purple-faced Prince, with its 1984 story. The article, titled “Purple Fame,” came shortly after the release of Prince's hit “Purple Rain.” Goldsmith, a well-known photographer of musicians, got a small credit by Warhol's image.

Warhol died in 1987. Following Prince's death, Vanity Fair paid his foundation $10,250 to use the orange-faced Prince portrait in a tribute issue. Goldsmith saw the cover and contacted the foundation seeking compensation, among other things. The foundation then went to court seeking to have Warhol’s images declared as not infringing on Goldsmith’s copyright. A lower court judge agreed with the foundation, but it lost on appeal.

Some amount of copying is acceptable under copyright law as “fair use.” To determine whether something counts as fair use, courts look to four factors set out in the federal Copyright Act of 1976. A lower court found that all four factors favored Goldsmith. Only the first factor — “the purpose and character of the use” of the work — was at issue in the Supreme Court case. Sotomayor wrote, “The first factor favors Goldsmith.”

In a statement, Joel Wachs, the president of The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, said the foundation disagrees with the court's decision but welcome the justices' “clarification that its decision is limited to that single licensing and does not question the legality of Andy Warhol’s creation of the Prince Series in 1984.”

Goldsmith said in a statement that she was “thrilled by today’s decision.” “This is a great day for photographers and other artists who make a living by licensing their art,” she said.

The case is The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts v. Lynn Goldsmith, 21-869.

Sourse: abcnews.go.com