For three decades, through three wars, the U.S. military draft was directed by Lewis B. Hershey, a general in the Army. Hershey established the first local draft board in 1941; eventually, there would be four thousand of them. These “little groups of neighbors,” as he described them, were charged with determining who should serve in the armed forces. This was a heavy responsibility. During Hershey’s tenure, the U.S. conscripted more than fourteen and a half million men, and hundreds of thousands of them died.

The boards, which adjudicated claims for reclassification or deferment on a case-by-case basis, had a distinct character. They were disproportionately white, white-collar, and elderly. According to analyses conducted in the nineteen-sixties, draft boards more often granted deferments to privileged young men, and poor Americans of color made up a disproportionate share of draftees. Though a conscript couldn’t buy his way out of service, as during the Civil War, it was still possible for him to avoid the draft by enrolling in college or in graduate or professional school. The system wasn’t fair, and many knew it. In 1966, President Lyndon B. Johnson convened a group of experts to study draft reform. They recommended a drastic overhaul to centralize the process, and argued, controversially, for randomizing it. What was needed, they wrote, was a lottery to decide who should fight, in which the “order of call” was “impartially and randomly determined.”

Many people did not find this idea appealing. Detractors argued that haphazardly drafting young men, some of whom were training for critical civilian positions, would be inefficient at best and destructive at worst. Merriam Trytten, a physicist by training, who was the president of the Scientific Manpower Commission—a nonpartisan group set up by the American Association for the Advancement of Science to advise the government on issues of scientific personnel—said that, under such a system, “scientific effort in the United States will pay a substantial penalty.” The commission’s executive secretary and eventual director, Betty Vetter, another authority on scientific workers, added that “the shock may be severe to many industries.” A Gallup poll conducted in 1966 found that only thirty-two per cent of Americans favored a lottery system.

Johnson did not follow his commission’s recommendations. But Richard Nixon, who inherited the Vietnam War, did. On December 1, 1969, Americans watched the first televised draft lottery. Three hundred and sixty-six blue capsules swirled around a glass vat until Alexander Pirnie, a Republican congressman from New York, selected one. Nineteen-year-olds who’d been born on September 14th would be called up first. Privileged young men were not exempt: Nixon’s son-in-law David Eisenhower—the grandson of Dwight Eisenhower, and the person after whom Camp David had been named—received a draft number of thirty, and ultimately joined the Navy. The Vietnam War remained unpopular, but the random draft was, comparatively speaking, embraced; among those under thirty, support for the war jumped by five per cent after the first lottery. Hershey, who had denounced the lottery, was soon “promoted” into a new job.

Today, the random draft is generally seen as a vast improvement over the previous system. It’s also an example of a rare phenomenon: a change that makes a consequential part of American society more random, not less. On the whole, randomness has been squeezed out of the systems that organize our lives. In the early twentieth century, the retail magnate John Wanamaker complained that, because the ads that he placed were seen more or less randomly, half his advertising budget was wasted: “The trouble is that I don’t know which half!” he said. But, today, Google’s ad-targeting algorithms insure that the right ads find us with uncanny accuracy. When we choose a movie or look for a date, apps take much of the guesswork out of the process; airplane seats are micro-categorized at different price points, and prices themselves are less random, thanks to sites such as Amazon. Educational institutions precisely rank their applicants, and parents and kids, in turn, consult college rankings to figure out where to apply.

As our society has become less random, it has become more unequal. Many people know that inequality has been rising steadily over time, but a less-remarked-on development is that there’s been a parallel geographic shift, with high- and low-income people moving into separate, ever more distinct communities. In 2019, the median household income in Washington, D.C., was $92,266. The corresponding figure for Mississippi was $45,792. Even locally, spatial differences are stark. New York City’s Fifteenth Congressional District, which covers the South Bronx, is the poorest in the nation, with a median income of thirty-one thousand dollars. The nation’s richest district, New York’s Twelfth, is just a mile or so to the south; it includes the Upper East Side and has a median income just shy of a hundred and twenty-five thousand dollars. Sorting occurs even in areas where people of multiple social classes overlap: people of different incomes often frequent different establishments on the same city block.

As a sociologist, I study inequality and what can be done about it. It is, to say the least, a difficult problem to solve. Manhattan, where I live, is situated in New York County, one of the nation’s richest; Bronx County, just a few miles to the north, is its poorest. People in New York County often vote Democratic, and Democrats usually support social spending. But, when rich people are asked to pay more in taxes, or to send their children to school with poorer kids, they tend to move. When this happens, the tax base erodes, and poorer communities struggle to fund high-quality public services. Even wealthy people who don’t leave can still withdraw from the commonweal, by privately acquiring goods that used to be public. As they stop riding the subway, or cease drinking tap water, or withdraw their kids from public schools, their support for progressive taxation wanes.

The core issue is that our social contract is based on place: we make decisions and fund our government in a fundamentally local way. This means that, the more we live in separate clusters, the less incentive we have to help one another, and that creates a feedback loop that worsens with time. Meanwhile, our political divisions deepen. We are more geographically polarized by social attitudes and partisanship than at any time since the Civil War. This is true across regions, within states, and even among neighborhoods. Political scientists argue about why this is happening—but nobody disputes that it is taking place.

I’ve come to believe that lotteries could help to crack this nut and make our society fairer and more equal. We can’t randomly assign where people live, of course. And we can’t integrate neighborhoods by fiat, either. We learned that lesson in the nineteen-seventies, when counties tried busing schoolchildren across town. Those programs aimed to create more racially and economically integrated schools; they resulted in the withdrawal of affluent students from urban public-school systems, and set off a political backlash that can still be felt today.

But there’s another route to consider. What if, instead of paying taxes where we reside, and then reaping their benefits locally, we sprinkled taxation and revenues randomly—and therefore evenly—across the United States? What if, instead of paying a third of my taxes to New York City and State, I instead paid them to Pod No. 2,264—a group to which I was randomly assigned by a lottery the year I turned eighteen? What if, instead of camping out on the sidewalk the night before the school-enrollment date in hopes of getting my kids into a well-funded public school, I received a monthly check from Pod 2,264 that was meant to pay for my children’s schooling wherever I wanted to send them? In such a system, the retreat of affluent people from the places where they live doesn’t matter. In fact, it doesn’t matter where anybody lives. Nobody can escape contributing to the public sphere, no matter how far they move.

Organizing everyone into randomly assigned pods may sound insane—and it isn’t likely to happen anytime soon, or at all—but it isn’t any crazier than the way things are set up now. Today, the vast inequalities across school districts, cities, counties, and states depend upon boundaries that evoke a prior, agrarian epoch. The whole idea that we should make policy by parish stems from the Elizabethan Poor Laws, which, at the end of the sixteenth century, set up hyper-local social safety nets; in a time of small-scale agriculture and cottage industries, when economies were regional and most people died within miles of where they were born, hyper-locality made sense. But it doesn’t make sense anymore. Today, Donald Trump can keep an apartment in his eponymous Fifth Avenue tower while relocating to Florida for tax purposes, and a friend of mine can count how many days she sets foot in New York State, aiming to keep the number below a hundred and eighty-four, so that she can be considered a “non-resident.” Localities aren’t what they used to be.

In fact, if we were truly determined to update our anachronistic, territorial system, we could do it by wearing G.P.S. trackers. We could be billed for our taxes based on where we actually spend our time—like wearing an E-ZPass for life. That’s the sort of measure it would take to synchronize the complexity of modern, mobile society with sixteenth-century agrarian political boundary-making. Sorting all Americans into randomized pods actually seems easier.

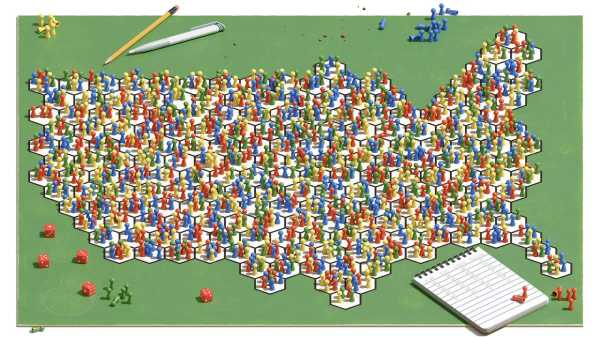

Here’s how the biggest lottery in human history might work. Every citizen or permanent resident would be assigned to a pool of a hundred thousand people across the United States on his or her eighteenth birthday. The assignment would be based on a random drawing of numbers, and would be permanent. Today, there are 3,144 counties in the United States. Now, in parallel, there would be thirty-three hundred pods. Counties, cities, and perhaps states would relinquish some of their fiscal authority. The government wouldn’t mandate where people live, but it would create durable links that transcend geography among randomly selected groups of citizens.

The pods wouldn’t be strictly limited to a hundred thousand people. Each pod would gain members whenever its number happened to come up in the lottery, and lose constituents through death, and so the actual population of any given pod might shift. With each census, the number of pods could also rise or fall along with the over-all population. Each pod, meanwhile, would contain Alaskans, Arkansans, New Yorkers, and so on. Simply by force of statistics, pods would have approximately the same median income; there are currently seven hundred and thirty-five billionaires in the United States, and they would be more or less equally apportioned. The pods would also be racially integrated, sex-balanced, and similar in terms of age profile. And they would be purple. Pod 2,222 would have roughly the same number of Republicans and Democrats as Pod 2. Each pod, in essence, would be a mini-me of the U.S. population.

Each pod would collect taxes, which would then be distributed among its members to pay for much of what counties and states once paid for: K-12 schooling, health care, unemployment, food stamps, and so on. Because the pods would be relatively small—a hundred thousand is about the population of Tuscaloosa, Alabama, or Davenport, Iowa—members could decide on spending priorities through online budget negotiations, direct voting, or a system akin to jury duty within the pod. Moreover, each pod would send one of thirty-three hundred representatives to a national legislature, where issues that affected the country as a whole would be decided: environmental policy, national defense, infrastructure, and so on. Ideally, those lawmakers would themselves be chosen by lottery.

Congress, in this scenario, would look very different from the cast of characters that haunts C-SPAN today. First, replacing five hundred and thirty-five elected officials with thirty-three hundred members would dilute the power of each individual legislator. The early Framers never intended for each congressperson to represent as many constituents as they do now; it’s just that the size of the House of Representatives has been frozen since 1913. (Until then, it grew with each census.)

With each representative answering to just a hundred thousand constituents, officeholders would be better able to know the will of the people. A larger Congress of thirty-three hundred would also mean that individual flamethrowers would wield less influence. And legislators, having been selected by lottery, wouldn’t feel beholden to big donors, or even to political parties. Congress would feel more like a jury of peers than a sclerotic body of fat cats.

What would life be like in a pod society? For one thing, my mother, my sister, my wife, my children, and I would almost certainly be in different pods. In fact, the odds would be high that I’d know no one in my pod in “real life.” Of course, I could purposely set out to meet my fellow-podders. In large metropolitan areas, local meetups of co-podders would likely emerge; in New York City, for example, there would be about twenty-five hundred members of each pod who could gather for potlucks or political debates. Undoubtedly, political differences and affiliations would still exist—there would still be conservatives and liberals, believers and atheists, libertarians, anarchists, Marxists, übercapitalists, and superpatriots. But the pods themselves would be incapable of developing these characteristics. All of us, no matter our views, would have to vote in groups that contained a cross-section of American outlooks. This would change the tenor of political debate. It would no longer be possible for politicians to play to their bases; instead, they’d have to appeal to everyone.

That’s not to say that the pod system itself would be politically neutral. Because each pod would contain a range of ages and incomes, voters might be more likely to favor ideas that benefit broad swaths of society—preventive care, educational spending, infrastructure, and so on. Pods might also try a broader range of approaches to problem-solving. In some respects, pod society would be libertarian: since podders wouldn’t be co-located, many programs would have to work by means of vouchers, which citizens could then spend in their local markets as they saw fit. Of course, certain place-based public goods would have to be funded and managed locally. But perhaps our disagreements over parks, policing, roads, water, sewage, and other local services would lessen if everything else were a little less local.

In recent years, thinkers in Silicon Valley have proposed a tech-centric version of this idea. Balaji Srinivasan and others write about “networked states”—online social unions that use cryptocurrency and blockchain technology to keep track of their citizens, acquire land, and provide social services to their members. Networked states, they argue, may someday achieve formal diplomatic recognition, becoming countries themselves. But a networked state is like a private pod. One is not randomly assigned to a networked state; one must apply, with an application that’s reviewed by a kind of co-op board. If anything, such an invention would make it easier, rather than harder, for the ultra-rich to wall themselves off from the rest of us. They wouldn’t even have to move to leave the polity.

Public pods won’t happen—but it’s still useful to blue-sky. In the midst of the Vietnam draft lottery, the political philosopher John Rawls proposed his own idealized blueprint for a fairer society, in a book called “A Theory of Justice.” In his imagined world, we cast our votes not from our current stations in life but from what he called the “original position”—a Platonic state in which we don’t know what place in the world we might occupy. Imagine if the federal budget were hashed out not by Nancy Pelosi and Mitch McConnell but by unborn souls who had no idea whether they would come into the world poor or rich, Black or white, male or female. Rawls argued that, in such a reality, utilitarianism—the pursuit of the greatest good for the greatest number—wouldn’t prevail. Instead, we would seek to improve the lot of the worst off, since any of us could draw a losing number. When important matters are determined by lottery, we become more empathetic.

As a political tool, lotteries have come and gone throughout history. Sortition—the selection of political officials by lot—was first practiced in Athens in the sixth century B.C.E., and later reappeared in Renaissance city-states such as Florence, Venice, and Lombardy, and in Switzerland and elsewhere. In recent years, citizens’ councils—randomly chosen groups of individuals who meet to hammer out a particular issue, such as climate policy—have been tried in Canada, France, Iceland, Ireland, and the U.K. Some political theorists, such as Hélène Landemore, Jane Mansbridge, and the Belgian writer David Van Reybrouck, have argued that randomly selected decision-makers who don’t have to campaign are less likely to be corrupt or self-interested than those who must run for office; people chosen at random are also unlikely to be typically privileged, power-hungry politicians. The wisdom of the crowd improves when the crowd is more diverse.

Much of this research suggests that, even if we’re never going to upgrade our country to a pod-based operating system, we can still use lotteries in more modest ways to make our society more podlike, blunting the impact of inequality in everyday life. Today, lotteries make cameo appearances—at the N.B.A. draft and during jury duty, in college-roommate assignments and green-card allocations, at T.S.A. screenings and the like. But there are many other settings in which they can be effective—especially if we recognize that they can be combined with meritocratic judgments. New Zealand and Switzerland have recently adopted a lottery-based approach to funding scientific research: grant applications receive funding on a random basis, but only after they’ve crossed a demanding peer-review threshold. Similarly, admissions at selective schools could be apportioned at random among applicants who are sufficiently qualified—an approach that might be fairer than having a small admissions committee decide among equally capable individuals. Civil-service jobs could be awarded by lot among the pool of candidates who pass the exam. In Ireland, a new program encourages artists by paying them a weekly stipend; nine thousand working artists applied for the benefit, and, rather than trying to objectively judge their art—an impossible task—administrators chose randomly among the eighty-two hundred people who qualified.

Lotteries could work for the assignment of certain civic responsibilities: street sweeping, PTA participation, park planting, and so on. They could help with the apportionment of burdens that no one wants to shoulder, such as the siting of toxic-waste dumps and prisons. And weighted lotteries, in which poorer people get more lottery tickets, could improve parts of our social safety net. Currently, the waiting lists for public housing and Section 8 housing vouchers are very long, and laws in some states insure that the homeless jump to the top of the queue. That sounds fair, but many families wait for years and never move up the list, and research has shown that the policy ends up incentivizing homelessness. A lottery conducted among eligible families whenever an apartment becomes available, with some weight given to need, would decrease incentives to game the queue by remaining unemployed, unmarried, or homeless.

Some of us would lose in a more lottery-based society. But many of us would win. And we might end up being more compassionate toward one another; we’d be forced to acknowledge that much of our lot is the luck of the draw. We argue endlessly about the meaning of luck, even if we don’t always realize it. How much are we responsible for what happens in our lives? What’s the difference between luck and choice? How much should society try to help the unfortunate? Much psychological research shows that Americans who believe that luck plays a large role in our lives tend to be more liberal, supporting redistributive policies. Yet almost all of us seem to wish for a society in which luck plays no role, and in which everyone gets what they deserve, whether through their own actions or through mutual aid.

Despite this common goal, we tend to reach for lotteries only as a last resort, as President Nixon did when waging an unpopular war. We tell ourselves that we are successfully squeezing randomness out of life, by means of ever more refined algorithms and targeted social policies. But one lesson of our pod-based thought experiment is that we already live under the reign of lotteries—lotteries of birth, of location, of economic and social fate. We’ll never truly randomize America, but even entertaining the possibility can help us see that it can be useful to acknowledge randomness, and even to incorporate rolls of the dice into our collective life. What if, instead of trying to erase luck, we embraced it? ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com