One of Thomas Wågström’s pictures has been hanging on the wall above my desk for many years. The picture shows a black surface of water, the patterns and whorls in it, the ceaseless motion that here is fixed in a final pattern, like a sort of rug, in this case a rug woven out of light and shadow. But the picture holds more than that, for at its lower left edge one glimpses the face of an animal: the slit of an eye, a muzzle, a bit of fur. It appears to be a seal, and it is on its way up through the blackness, and in the very next instant, one might imagine, it will pierce through the water. But it hasn’t done so yet; the slit of the eye and the muzzle hover just below the surface and seem almost a part of it.

Every time I look at this picture, and I have looked at it every day for at least a decade, the really big question brushes by me—the question about life and the lifeless from which life springs. The picture gives one the sensation that life exists against all odds, but also that it is robust. It is an incredibly optimistic image, an image of defiance, of will, of irrepressibility, of freedom. And it is so marvellously compressed: the living animal amid lifeless matter. How did the one arise from the other? And how has it managed to remain in existence? Daily life does not invite such questions. Instead, it breaks them down and denies them space, for although mystery is all around us it doesn’t take the form of mystery. It is disguised, for instance, as the rubbish you take out to the rubbish bin on a spring evening, as the margarine you put back in the fridge and the knife you try to rinse the yellow remains off of while the tap water is still cold and the water just slides off the butter instead of carrying it down into the drain, as a pubic hair stuck to your skin which causes your piss to divide so that one stream hits the porcelain rim and a sprinkle of tiny drops of urine settles on the bathroom floor, or as the bedsheet you know you ought to change, but can’t be bothered to, remains yet another night, rank and crinkled and somehow saturated with carnality. That our lives are made up of such minor occurrences, which take place, as it were, close to the ground, with no room for an external gaze, is the main reason that I have had this picture, of the black water with the seal pushing its way up through it, hanging on the wall above my desk—it opens up a different space, and lets me breathe.

The opening picture of Wågström’s self-published book, “Case Closed” (2022), shows a concrete tunnel or underpass. The floor is light-colored, and the walls are black, and the strip of floor leading into the tunnel gets narrower and narrower until it is swallowed up by the blackness. A tunnel leading from light into darkness—is it possible to look at it and not think of death? There are several pictures with similar motifs in the book, roads leading into the darkness, even one leading into the darkness of a funeral chapel. These roads leading to nothing set a mood, charging the rest of the pictures with their emptiness, but they also set up an ambivalence, because what we see is not nothing, is not death. On the contrary, it is something: a concrete tunnel, man-made; a gravel road, man-made; a funeral chapel, man-made; living tufts of grass; living trees; a life-giving sky full of light and oxygen. And yet it is impossible to look at them and not think of death. It has to do with the iconography, of course—the journey from light into darkness is an archetypal image, one of the few so deeply rooted in the culture that one doesn’t need to see it or have it explained to understand what it means. But there is something else going on in these pictures, too.

All photographs are about transience. This lies in the very nature of photography, since everything in the world is continually changing, and what a photo depicts vanishes the next instant, or becomes something else. One could say that all photography is about loss. But one could also say the opposite: photographs salvage something from time, as from a burning house.

Many of Wågström’s photographs seem to want to suspend time, not by freezing the arbitrary moment but by seeking that which is constant in it. The picture of the tunnel is obviously taken at a particular moment in time, but nothing in that moment is moving and nothing of what we see—three concrete surfaces—will move in the foreseeable future. The picture is concerned with the nonhuman, not necessarily with death as such but with nonhuman time, that which endures: the background against which everything in these pictures, including people, becomes visible.

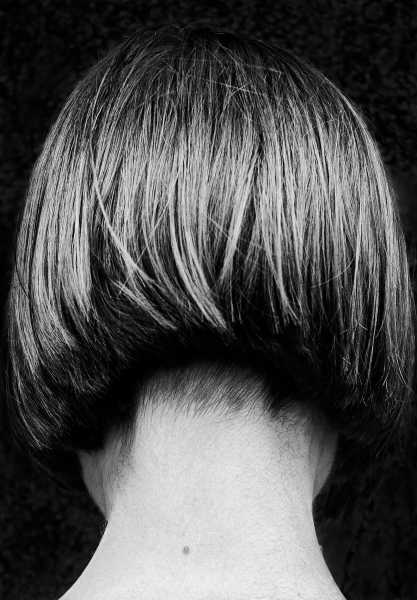

Another picture also depicts a passage, but this one is indoors and completely packed with people. They are all sitting bent toward the floor, so that we only see the backs of their bodies. Their heads are all shaven, and they are all dressed in identical clothes, so that all individuality has been obliterated. They are not Sven and Sture and Björn; these are specimens of man, the species. The shaven heads are round and luminously white amid the darkness: they look like eggs. And although the identical clothes are uniforms and the men are obviously soldiers, trained to kill, there is something vulnerable about these humans; their brittle, egg-like heads look as if they might be easy to smash against the smooth, tiled walls. The presence of bodies along with the absence of faces—which Wågström also explored in depth in a series on necks—also creates a powerful sense of people as animals; the mass of limbs, backs, and bellies could just as well have belonged to a seal colony or a herd of pigs, and inside the narrow passage, with its hard, unchanging walls, the organic mass gives the viewer an impression of mindless, uncontrolled growth.

The pictures in Wågström’s book span four decades, and their motifs are many and varied, but they are all connected to something unmistakeable—which I think is that they are more interested in the conditions that human beings exist under than in the lives that they live. The people in the photos are often viewed from a great distance, and when they are depicted up close, as in the narrow passage, they are frequently faceless. In this respect, the necks are typical, and that series of photographs is as simple as it is ingenious. By taking portraits of the back of the head, which, of course, is just as individual and distinctive of the person portrayed as the face is, the human comes to seem alien, and the difference between culture and nature becomes apparent: culture is what takes place between us, within the circle of faces, and nature is what lies outside it. It comes almost as a shock when one of the few gazes that meets our own in his book belongs to a doll. It is as if the lifeless world is staring back at us.

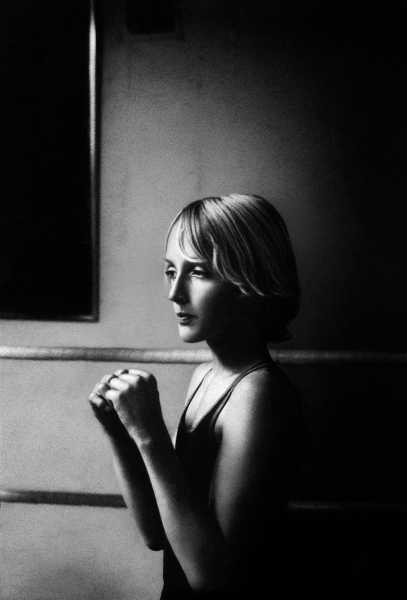

All of the photographs exert a pull on us, all of them are filled with atmosphere and meaning, which the viewer takes in immediately, at first glance. They are also all connected, all related to one another, by virtue of the artistic temperament and the world view of which they are an expression, and which is to be found in a characteristic timbre that is easy to recognize but hard to define. They are existentially charged: a loop of rope has no less of a presence than that of a sleeping soldier, simply because it exists. The pictures often take in things that the humans themselves don’t see, such as the lovely series of walkers on the ice and in the snow-covered forest, where the people who are out walking seem unaware of one another and the patterns that they form together. A similar motif, but more concentrated, is found in the picture of the staircase and the people walking on it, giving the viewer an acute sense that they are each living in a separate world, without an eye or thought for the whole of which they form a part. All the more powerful is the effect produced by the encounter of two old people on a sidewalk, seen from high above in a sequence of three pictures, where their shadows are so long and black and sharply defined that it looks like two separate encounters, one between their bodies and another between their shadows, which are hard not to think of as their souls, and which seem painfully alone as they continue on their separate paths.

Another Wågström picture that has been hanging on the wall above my desk for many years, and which I also used for the cover of a book, shows an urban landscape, with five white tower blocks and a church spire rearing up from the darkness in the distance. I know that the city is Stockholm and that the tower blocks are deindividualized in much the same way as the soldiers, so when I look at them all I see are blocks, bathed in a peculiar light that forms an arc in the sky behind them. What the pictures show is real and concrete, but the strange light somehow cancels out the tangible, removing it from time and place. The picture could just as well be presenting the future as the present or the past, and that is how I think of it every time I see it, as a photograph of the future.

In a similar way, I think of the three pictures that conclude Wågström’s book—of foggy, rain-filled landscapes, so unlike all the other pictures—as something from the past. Nothing in them is specific to our time, not the fields or the trees, not the sky, the rain, the fog, the roofs of the houses or the tower in the distance, and something about the form that I am unable to define gives the three photographs a faint nineteenth-century air. Photography is the veritable art of the moment; it must necessarily relate to the here and now, to what is happening and what exists in the moment that the camera’s release is pressed. Many of Wågström’s pictures seek to conquer the moment, I think, by making visible what is relative about time—the time of the clouds is not the same as the time of the trees, the trees’ time is not the same as the time of the mountains, the mountains’ time is not the same as our time, and our time is not the same as the time in a photograph. The seal in the image is trapped there, just below the surface—case closed—but the mystery is kept open, and that is what makes it art.

(Translated, from the Norwegian, by Ingvild Burkey.)

This is drawn from “Case Closed.”

Sourse: newyorker.com