Chicago: A Novel, by David Mamet, 2018, Custom House, 352 pages

David Mamet is a writer whose literary scalpel shows no mercy. He cuts away at the niceties of human analysis to show the sustainable primal instincts that, like it or loathe it, still determine much of our behavior. Mamet once explained that he never had any interest in depicting drama involving one heroic character who wears a white hat versus one villainous character in a black hat. Everyone loves those stories as they unfold, Mamet argued, and forgets them five minutes after leaving the theater.

His body of work is legendary, especially the Pulitzer Prize-winning play Glengarry Glen Ross, brilliantly adapted for the screen with a Mount Rushmore cast. To call the orientation of the salesmen in the story “cutthroat” almost seems complimentary.

Alchemizing the substance of Aristotle and Hemingway into inspiration, Mamet always shows people in conflict who are equally comprised of evil and virtue. His plays and films are often difficult to watch, even as they entertain, because they corner the viewer into asking, “Which one of these people am I like?” The answer is usually all of them.

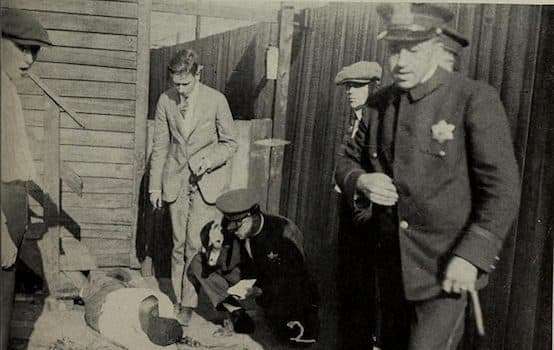

After a brief turn towards political polemicist and several plays that garnered mixed reviews, Mamet has returned to his old form not with a play but a novel. Chicago, set in the 1920s and featuring a hard-drinking newspaperman named Mike, is Mamet’s exercise of the genre impulse. A murder mystery surrounding the death of Mike’s lover, the narrative serves Mamet’s penchant for applying his enticingly hardboiled yet high-thinking approach to human conflict, both the interpersonal and institutional varieties, to a period when Mamet’s native city and much of America were still “on the make,” to use American writer Nelson Algren’s famous phrase.

Mobsters and hustlers of different ethnicities clash with corrupt politicians, besotted journalists discuss the vulgarities and grandiosities of life with black bordello owners, and Catholics and Protestants dine with safecracking thieves. Mamet’s setting is both seductive and illuminative, but the story is not without flaws.

It seems that Mamet aimed for Raymond Chandler’s sweet spot between plot and character study. But he misses narrowly. The most significant frustration for this reader was that Chicago does not have enough plot to succeed as a straightforward mystery, but it has too much plot to qualify as literary fiction.

Mamet’s collections of personal essays, The Cabin and Make-Believe Town, are brilliant and quietly moving reflections on the subtle wounds and joys of life, whether a backroom poker game that ends with a broken friendship or the peace and comfort of becoming a regular at a greasy spoon diner. But his novels, like a beautiful boat floating along aimlessly, often offer searing and soaring prose in search of a story. Chicago, although more deft and intriguing than previous novels The Village and Three War Stories, suffers from this characteristic rootlessness.

It is not for reasons of excellence, but what Mamet manages to capture and dramatize in his novel, that makes it enjoyable and even important to read during America’s contemporary cultural coalescence of various harmful developments: namely the collapse of political discourse into the warring invective of two identity-obsessed tribes, the bipartisan celebration of victimhood status, and the emptying of creativity into kitsch and juvenile spectacle. The grit, tenacity, and independent spirit of Mamet’s characters, when held in contrast with the various narratives of victimhood that now too often pass for entertainment, feel tragically anachronistic.

Despite its faults, the novel possesses a hypnotic power that emanates from Mamet’s brilliant dialogue (he’s one of the best dialogue writers of the American literary heritage) and its hungry energy. The story moves at the pace of the world it depicts.

Algren, in his most famous lines from Chicago: City on the Make, compares the relationship he joyfully and painfully endures with his subject to “loving a woman with a broken nose.” He explains, “You may well find lovelier lovelies, but never a lovely so real.” Carl Sandburg, who christened Chicago the “city of big shoulders,” wrote, “They tell me you are wicked and I believe them, for I have seen your painted women under the gas lamps luring the farm boys. / And they tell me you are crooked and I answer: yes, it is true I have seen the gunman kill and go free to kill again.” In a declaration of love for his city, he then compliments Chicago as “a tall bold slugger set vivid against the little soft cities; / Fierce as a dog with tongue lapping for action…”

Mamet’s Chicago reflects both Algren and Sandburg. It is a city alive with the momentum of the fighter charging at the sound of the bell. Peekaboo, a black woman who owns a whorehouse and acts as oracle of the underground to Mike as he investigates the hidden night side of the city, is the most intelligent, complex, and seductive character of the story. She is an independent powerhouse yet earns her handsome living in one of the few ways possible for a black woman of her time. She learns to tolerate subtle but persistent forms of disrespect. That she is smarter and tougher than everyone around her is exciting and frustrating in equal measure. It is narrow, stupid, and even demeaning to call her a “victim.” Yet her options are limited through the construction of legal, financial, and social barriers.

Mamet’s description of The Stroll, a black neighborhood at night, more perceptively captures the contradictions of the American racial experience than nearly any essay in the identity politics genre, rendering, in the process, every Twitter feed and cable news shouting battle as vulgar piffle:

There were, of course, idlers and street people, hustling goods or services, papers, shoeshines, notions, sex, tickets (real and counterfeit) for various of the night’s entertainments, liquor, cigarettes, and drugs.

There were the ropers and doormen for the clubs, out early, smoking and chatting. There were crap games in the alleys, and on the loading docks on the side streets off of State Street.

There were the most beautiful women Mike had ever seen, walking, purposefully, to work at the clubs: cigarette girls, performers, B-girls, waitresses, semipro prostitutes; there was a countercurrent of women having finished work at the shops, the millineries, clothing stores, manicure and beauty salons, tailor shops, and restaurants.

The men, lounging, strolling, entering or leaving the occasions of the afternoon, eyed the women, Mike thought, with a respectful frankness. But the banter, and the competition for the best comment or riposte, ceased as soon as the inhabitants were aware of the white man.

The life stopped in that portion of the street within his orbit, and he left.

The colorful people of color on the Stroll are not seeking sympathy or support, only individuality and solitude; the allowance to create their own community without interference or invasion. Chicago was full of similar ethnic enclaves, many of them flourishing to a greater degree than black neighborhoods in the early 20th century due to the absence of redlining, hiring discrimination, and early exclusion from trade unions with which blacks had to contend. It was the energy of hustling that acted as a source of vitality to the city. The steady depletion of that power grid has now left our culture mediocre and, despite the variety promised by digital technology, increasingly singular and stale.

Hustling ultimately is an empty pursuit, however. It tantalizes with the temptation of wealth, pleasure, and achievement, but it is spiritually bankrupt.

Mamet’s novel reaches for the accomplishment of simultaneously capturing the dynamism of a hustling society and depicting its corroded core. Whenever his characters attempt to aim for values higher than self-gain and profit, they find that only depression or death awaits them at the end of the transaction.

Chicago is set into motion by the aborted courtship between Mike and his lover. Their passion is sexual but also virtuous. They are devoted to each other with an innocence that transcends the cynicism of his seen-it-all occupation as newsman and her family’s criminal connections. So, naturally, she is murdered.

Reviewers of Chicago have almost unanimously quoted a particularly characteristic portion of Mamet dialogue, with approval but seemingly oblivious to its function as cultural indictment in the story:

“The Chinese,” Doyle said, “invented gunpowder. And used it, just as we do now, to foil evil spirits.”

“The question is, then,” Mike said, “what is evil?”

“Well, that is decided by the fellow holding the gun.”

In a hustling society, it is inevitable that might makes right, and wealth equals wisdom. The principles of honor, gallantry, and integrity can struggle in an underdog war for attrition, but more often than not they will find themselves going to the mattresses. Mamet provides flashes and glimpses of virtue in this cynical novel, but they can never quite emerge into plain view. The novel’s brilliance and profound relevance, perhaps unintentional, rests in its central struggle.

David Masciotra is the author of four books, including Mellencamp: American Troubadour (University Press of Kentucky) and Barack Obama: Invisible Man (Eyewear Publishing).

Sourse: theamericanconservative.com