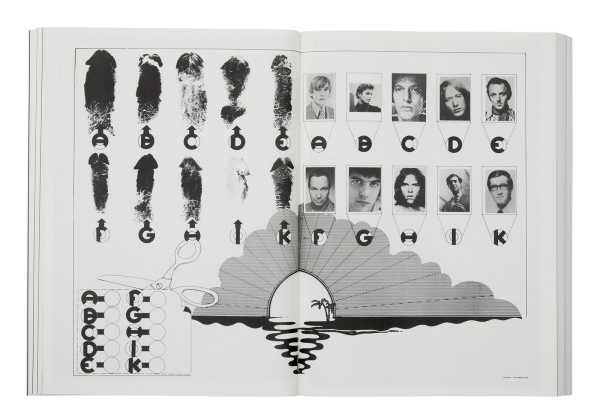

Newspaper, published out of an East Village apartment between 1968 and 1971, was one of a number of scrappy print publications circulating downtown in those years. Most of them were more radical, less serious, or far sexier alternatives to the established Village Voice. Unlike Rat, the East Village Other, or Screw, though, Newspaper’s news involved no words, only pictures. Other than an all-caps logo, the only type was tiny and used for the occasional caption or credit; an early issue included the easily overlooked information that five dollars, addressed to Steve Lawrence at 188 Second Avenue, would get you five bi-monthly issues.

Artwork by Stephen Paley, courtesy Primary Information

Artwork by Paul Thek and Edwin Klein, courtesy Primary Information

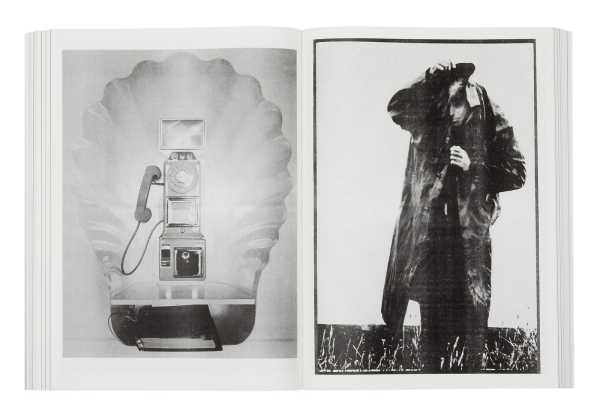

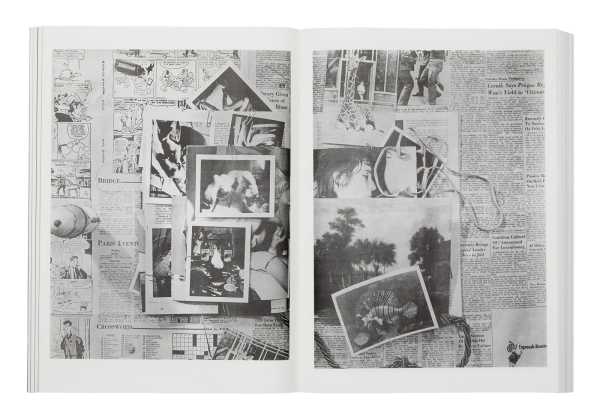

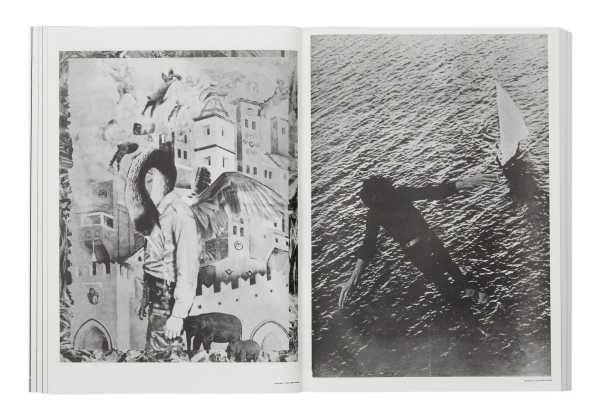

Lawrence, a handsome, lanky Texan, was just twenty-two and relatively new to New York when he became the publisher, designer, and driving force behind Newspaper. Its signature feature was what he called “Environments”—salon-style arrangements of erotica, exotica, nature studies, news photos, found snapshots, and celebrity pix. But it was Newspaper’s size that really set it apart. Folded in half like the early issues of Rolling Stone or like Andy Warhol’s Interview, it resembled a tall tabloid; spread open, it was just under two feet tall and nearly three feet wide—the scale of an art work. Readers tacked pages up on their walls.

Artwork by Maurice Hogenboom, courtesy Primary Information

Artwork by Joseph Raffael, courtesy Primary Information

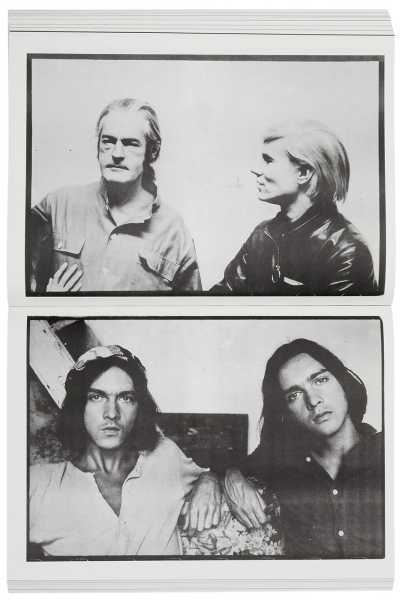

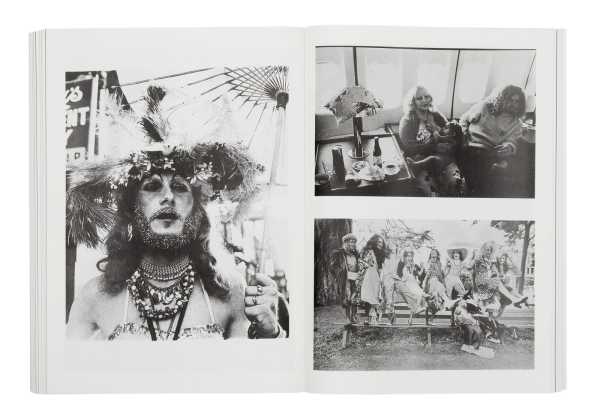

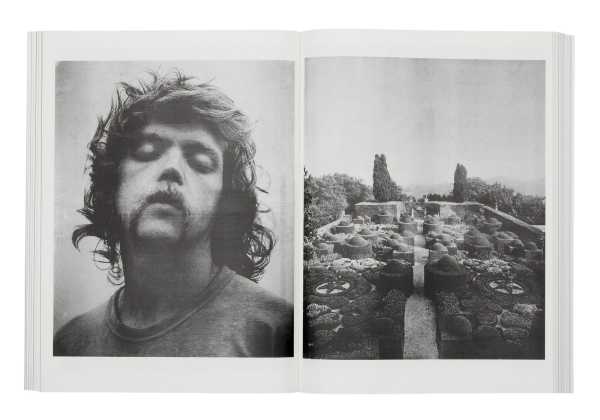

You’ll see why if you leaf through a hefty new volume from the publisher Primary Information collecting reprints of Newspaper’s fourteen-issue run. One of Lawrence’s early connections in New York was the photographer Peter Hujar. The two were lovers for a time, and they were roommates at the Second Avenue address throughout the years Lawrence was putting out his paper. (Hujar eventually moved into a loft directly across the street, where he remained until his death, in 1987.) Hujar’s photographs were also Newspaper’s most regular feature, with a pair appearing on facing pages in nearly every issue. Before any book of Hujar’s own (“Portraits in Life and Death,” the first of only two published in his lifetime, came out in 1976), Newspaper was his main outlet, and the reprint is full of work that hasn’t been seen since. The range is remarkable, from surprisingly tender closeups of skeletal figures in the Palermo catacombs to the remains of a Chinese restaurant dinner; from the Warhol star Jackie Curtis in a reflective moment to a startlingly elegant nude of a friend’s young daughter. There are portraits of the artist Louise Nevelson, the Village Voice columnist Jill Johnston, the dancer Deborah Hay, the gay-rights activist Jim Fouratt (Hujar’s boyfriend at the time), and, occupying a large portion of one issue, a collection of studio portraits of the gender-bending San Francisco performance group the Cockettes at their most exuberant and engaging.

Left image by Peter Hujar © Estate of Peter Hujar, right images unattributed, courtesy the Estate of Peter Hujar and Primary Information

Left image by Peter Hujar © Estate of Peter Hujar, right image unattributed, courtesy the Estate of Peter Hujar and Primary Information

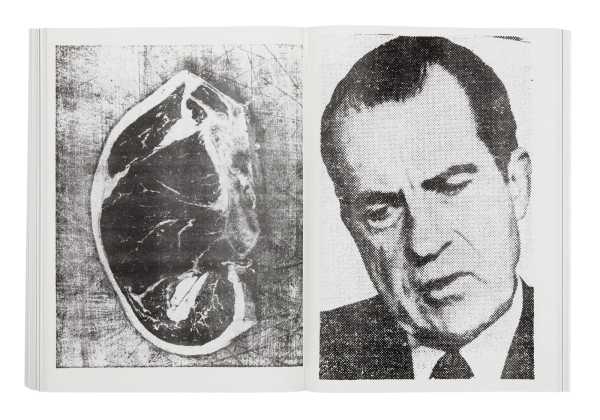

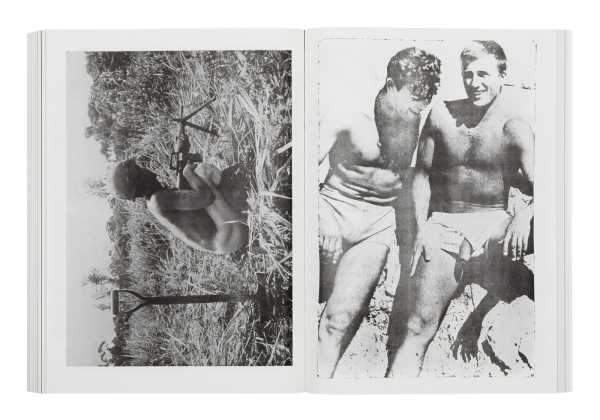

Although Newspaper had no formal masthead, Primary Information credits Hujar with an editorial role, if only because so many of the paper’s contributors came from his sprawling social circle: Richard Avedon, Diane Arbus, Lucas Samaras, Ray Johnson, Paul Thek, Peter Beard, Warhol. It’s a stunning list given that Newspaper was in many ways always a tenuous venture. The first issue cost Lawrence five hundred dollars. Subsequent issues were never sure things. But Newspaper’s eccentricity and nerve were just right for the times, and when it came to knockout visual impact the paper had no rivals. Occasionally, it was also politically radical. A center spread in the January, 1970, issue was devoted to an indelible Art Workers’ Coalition poster showing a photograph of slaughtered Vietnamese women and children with captions reading “Q. And babies? A. And babies.” That summer’s issue closed with a sequence of super-grainy, appropriated news photos—of the killings at Kent State, the war in Vietnam, protests and counter-protests—culminating in a closeup of Richard Nixon across from a picture of a slab of raw steak.

Artwork unattributed, courtesy Primary Information

Artwork unattributed, courtesy Primary Information

But sex was Newspaper’s special sauce. Richard Bernstein, famous for his covers for Interview, put a glamorous, bare-chested Candy Darling on the cover of the October, 1969, issue, with a Playboy-style nude centerfold within. (The impressive penis was not, in fact, Darling’s but that of another model, which only made the effect more sensational.) Newspaper’s sensibility and many of its contributors were queer, a fact that tends to stand out more obviously in retrospect. Gender fluidity was business as usual in the East Village of the early seventies; if Newspaper’s readers didn’t entirely take it for granted then they were at least unalarmed.

At the end of the new book, a meticulously researched time line by the young art historian Marcelo Gabriel Yáñez fills in Lawrence’s life after Newspaper. He published three additional issues in 1975, under the name The Picture Newspaper (though they’ve been excluded from the volume because they were partly in color and the reprint is strictly in black and white). In the following years, he bounced among odd jobs and suffered from substance abuse. He died in 1983, at the age of thirty-eight, possibly from AIDS, with his moment of alt-press triumph well behind him. But his paper’s fleeting contribution to art history was commemorated, in 1970, when the curator Kynaston McShine included it in “Information,” his now legendary MOMA show dedicated to new, mostly conceptual work. Newspaper’s issue from that summer, pasted from floor to ceiling on one of the museum’s walls, was not only one of the most concrete pieces of art in the exhibition but one of the most memorable. Downtown moxie and militancy knocked them dead uptown.

Artwork by Gerald Laing courtesy Primary Information

Sourse: newyorker.com