This year’s list of Best Picture nominees feels dispiritingly familiar. “Top Gun: Maverick” and “Avatar: The Way of Water” are two colossally budgeted sequels written to internationally crowd-pleasing Hollywood specifications. And, though the non-sequel “Everything Everywhere All at Once” has been celebrated as a burst of cinematic creativity, its strenuous visual and sociopolitical exertions do not mask its adherence to the storytelling tropes of a superhero picture. No element of its narrative, in other words, would surprise the script guru Robert McKee, whose popular guide to screenwriting, “Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting,” was published more than twenty-five years ago.

Among those averse to genre spectacle and Oscar-baiting melodrama, McKee has become a byword for screenwriting structures as cynical and manipulative as they are widely employed. (Akiva Goldsman, a specialist in big-budget adaptations of existing properties—“The Client,” “Batman & Robin,” “The Da Vinci Code”—is probably McKee’s most notable adherent.) When I lived in Los Angeles, it wasn’t unusual to be in a café, surrounded by aspiring screenwriters with laptops running Final Draft, who were obsessing aloud over Inciting Incidents, Turning Points, and Major Dramatic Questions. In “Story,” McKee bestows these concepts (and many more) with capital letters.

McKee celebrates what he calls Classical Design: “Timeless and transcultural, fundamental to every earthly society,” stories of Classical Design are “built around an active protagonist who struggles against primarily external forces of antagonism to pursue his or her desire, through continuous time, within a consistent and causally connected fictional reality, to a closed ending of absolute, irreversible change.” Against this almighty Archplot, McKee first contrasts the Miniplot, which “strives for simplicity and economy while retaining enough of the classical that the film will still satisfy the audience.” Then comes the Antiplot, which “doesn’t reduce the Classical but reverses it, contradicting traditional forms to exploit, perhaps ridicule the very idea of formal principles”—and which has a tendency for “extravagance and self-conscious overstatement.” Accusations of extravagance and overstatement may sound a bit rich when couched in this kind of prose, but McKee’s first career was as an actor: his pronouncements sound more convincing when he personally thunders them.

The whole of “Story” reads like the passages quoted above, and exudes a hostility toward the deliberate breakage of narrative or cinematic convention. The Art Film, McKee writes, “favors the intellect by smothering strong emotion under a blanket of mood, while through enigma, symbolism, or unresolved tensions it invites interpretation and analysis in the postfilm ritual of café criticism.” (As McKee makes clear several times in the book, he is not a fan of café criticism.) He frames deviation from Classical Design as nothing more than petulant reaction. “The avant-garde exists to oppose the popular and commercial, until it too becomes popular and commercial, then it turns to attack itself,” he writes. If Art Films “went hot and were raking in money,” the avant-garde would “seize the Classical for its own.”

Such passages make me wonder to what extent McKee believes all this, or if he’s simply swept along by his own zeal for the one true screenwriting faith. This quasi-religious confidence in his message accounts, in part, for his seminars’ decades of robust attendance, as does the blunt, sometimes profane manner in which he expresses that message. Yet, for all his sound and fury onstage, McKee did not put himself forth as a lawgiver in his seminars, nor does he in “Story,” whose introduction promises “principles, not rules” and “eternal, universal forms, not formulas.” His interpreters have nevertheless derived from his work sets of commandments, meant to assure deliverance to Hollywood fame and fortune. And, when a film fails, McKee shows no hesitation in explaining how its screenwriter strayed from the path.

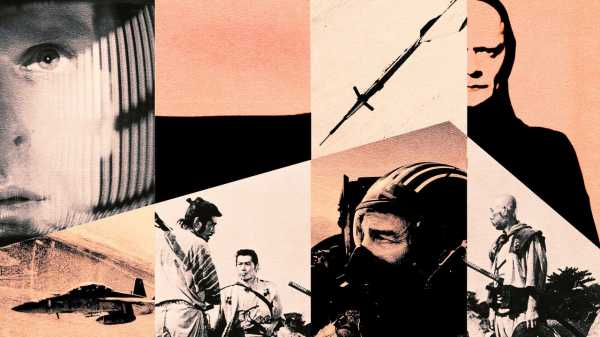

Yet, among his defining examples of the Archplot, McKee includes such cinephilically unimpeachable pictures as “The Grand Illusion,” “Seven Samurai,” “2001: A Space Odyssey,” and “The Seventh Seal.” For Ingmar Bergman, in particular, he exhibits a near-reverent appreciation, calling him “one of the cinema’s best directors because he is, in my opinion, the cinema’s finest screenwriter.” Along with the likes of Federico Fellini, Luis Buñuel, Michelangelo Antonioni, and Alain Resnais, Bergman was one of the “brilliant Continental filmmakers” who “challenged Hollywood’s dominance” in the decades after the Second World War, but, “with the death or retirement of these masters, the last twenty-five years have seen a slow decay in the quality of European films.”

Twenty-five years later, we lost Jean-Luc Godard, the last of the name-brand European auteurs who emerged in the cinematically fertile period “from the rise of Neo-realism to the high tide of the New Wave.” McKee uses “Weekend” to exemplify the Antiplot, but gives its transgressions against storytelling a pass because they constitute “an expression of the subjective state of mind of the filmmaker.” Still, the reader must remember that “Godard made ‘Breathless’ before ‘Weekend,’ ” and thus learned the supposed rules before he broke them. More surprising are “Story” ’s references, not obviously disapproving, to the work of Peter Greenaway. In many ways the anti-McKee, Greenaway has dedicated his long filmmaking career (whose popularity peaked in the nineteen-eighties, with such mannered, brazen pictures as “The Draughtsman’s Contract” and “The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover”) to freeing cinema from words on a page, and indeed from story itself.

“We have not seen any cinema yet,” Greenaway writes, in a 2001 essay published in the magazine Zoetrope: All-Story. “We have only seen 105 years of illustrated text.” In most every major film, one senses the director “illustrating the words first, making the pictures after, and, alas, so often not making pictures at all, but holding up the camera to do its mimetic worst.” That “cinema is not an excuse for illustrated literature” owes in large part to its being fundamentally unsuited to storytelling in the literary sense. The best pictures, according to Greenaway, comprise “atmosphere, ambience, performance, style, an emotional attitude, gestures, singular events, a particular audio-visual experience that does not rely on the story. Besides, nine times out of ten, you will not remember the story.”

Greenaway and McKee do agree on the separation of film and literature (which manifests amusingly in their shared disdain for “The English Patient”). Hence, McKee’s well-known injunction against explanatory voice-over narration. “More and more films by some of the finest directors from Hollywood and Europe indulge in this indolent practice,” he writes, in “Story.” “They saturate the screen with lush photography and lavish production values, then tie images together with a voice droning on the soundtrack, turning the cinema into what was once known as Classic Comic Books.” This is a reference to the defunct publication Classics Illustrated, which adapted novels such as “Ivanhoe,” “Les Misérables,” “and “Moby-Dick” into cartoons. “That’s fine for children, but it’s not cinema,” McKee declares.

In setting children’s comic books against cinema back in 1997—a year when Hollywood favored disasters and space aliens over superheroes—McKee was well ahead of his time. Just a few years ago, Martin Scorsese drew social-media attacks by likening the movies of the Marvel Cinematic Universe to theme parks. When he contends that such productions have nothing to do with “trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being,” he could be channelling McKee, for whom emotion and psychology are absolutely central to storytelling, and thus to cinema. Classical Design is “a mirror of the human mind,” McKee notes, because we see ourselves as the underdog protagonists of our own lives, often antagonized and sometimes, for better or worse, irreversibly changed.

Throughout “Story,” McKee frequently cites middlebrow pictures from the nineteen-seventies and early eighties such as “Ordinary People” “Chinatown,” “Kramer vs. Kramer,” and “Tender Mercies” as shining examples of the screenwriter’s art. These films are hardly invulnerable to criticism, not least owing to the airlessness induced by incessantly driving at particular themes (or, as McKee would see it, by their strong Controlling Ideas). But they do demonstrate an authentic concern with adult life, a quality now almost extinct in Hollywood. “Story isn’t a flight from reality but a vehicle that carries us on our search for reality, our best effort to make sense out of the anarchy of existence,” McKee writes. That sentence reflects the bombastic tendencies of his prose but also the essential soundness of certain of his observations. Art worthy of the name turns us not away from life but toward it.

Even if McKee’s kind of movie still gets made, it’s often promptly consigned to the realm of deep-streaming “content” to compete with countless television series—a form for which McKee has actually expressed great enthusiasm. “Television, without question, is the most creative medium to write today,” he said way back in 2012. “It is doing things with storytelling that are really wonderful and exciting, and it has length greater than any novel.” Since then, television has come to constitute a kind of missing link between cinema and literature: take HBO’s familial saga “Succession,” whose intrigue, satire, narrative complication, and sheer length could once have been realized only in an epic novel. Current television offers few characters as essentially novelistic as the show’s central patriarch, played by Brian Cox—whose most memorable previous work includes a voluble, profane turn as none other than Robert McKee.

Cox played McKee in Spike Jonze’s “Adaptation,” which stars Nicolas Cage as a fictionalized version of the film’s screenwriter, Charlie Kaufman. Tasked with writing a screenplay that adapts “The Orchid Thief,” Susan Orlean’s discursive journalistic portrait of a rogue Florida horticulturist, the high-minded onscreen Kaufman soon grows desperate enough to attend one of McKee’s three-day “Story” seminars. As McKee recalled in an interview, Kaufman had written him into the script because he “needed somebody to represent Hollywood, in an antagonistic way.” This need was dictated by the “inner conflict” (conflict being the essence of an Archplot) driving the script’s narrative, which is “how to make a commercial art movie.” Cage-as-Kaufman puts the central question differently: “Why can’t there be a movie simply about flowers?”

Though it came out twenty years ago this past December, “Adaptation” now looks like an artifact of a more advanced civilization. Were its mixture of Hollywood stars and production values with brazen reflexivity and inventiveness attempted today, I can imagine it only somehow suppressed. “Adaptation” is still exhilarating, but it isn’t encouraging: the film’s ironic third-act descent into hack-writer tropes (seemingly written by Kaufman’s fictional twin brother, Donald, an enthusiastic convert to McKeeism) implies, as the critic Will Sloan writes, “that you actually can’t make a movie that’s ‘just about flowers.’ ” But, Sloan continues, “people can, and have, made beautiful and lyrical movies that don’t indulge in ‘Hollywood clichés’ and move at a rhythm that would be alien to Robert McKee.” Yasujiro Ozu, for example, “or Hou Hsiao-hsien or Jonas Mekas could make a wonderful movie about flowers.”

Mekas died in 2019, Ozu has been gone nearly sixty years, and the septuagenarian Hou has, like Greenaway, reached the “late” stage of his career. So, for that matter, has the now eighty-two-year-old McKee, who conducted his final live round of seminars last fall but, in a recent burst of productivity, has also followed up “Story” with books on dialogue, character, and action. As for filmmaking, it remains voluntarily confined to a cramped corner of the virtually infinite creative space at its disposal, like a farm animal growing bony and haggard as it perversely grazes the same small, barren patch of a vast, open field. Cinema is now a hundred and twenty-eight years old, yet to anyone conscious of its possibilities beyond mere storytelling it remains, as Greenaway argued, practically nonexistent. Will a guru come forth to tell us how to invent it? ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com