It’s rare these days to have an unvarnished, unexpected encounter with a work of art. So much of what we see tends to be primed by advertorial buzz or social-media mentions—that squelchy stuff on top of the reviews, the advertisements, and the friendly tips that structure modern consumption. I seldom experience, or let myself experience, walking into a gallery or concert hall knowing nothing of what I’ll find inside. But that’s what I did last fall, at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Busan, South Korea. The Busan Biennale had taken over most of the museum, a rectangular building with a lush, living façade—a “vertical garden” of plant species native to Korea. The exhibition inside was admirably global: artists from twenty-five nations were grouped under the theme of “We, on the Rising Wave,” a nod to Busan’s history as an international port.

I started on floor one, and jotted a few admiring notes—about the spare, willowy drawings of Qavavau Manumie, an Inuit artist from Nunavut, Canada, and a mournful eco-installation by Choong Sup Lim, a multi-disciplinary artist who grew up south of Seoul. Then, in a gallery on the lower floor, my body reacted before my mind. The room was all oil paintings by a single artist—two dozen of them, arranged in order of production, across four mint-colored walls. Scenes of Busan were rendered in strong horizontal lines, using an exaggerated linear perspective that made them simultaneously representational and otherworldly. They seemed to tell the entire history of modern Korea, from the colonial era, through civil war, to the digital present. Small, indistinct figures—of railroaders, mothers, fishermen, and commuters—dotted each tableau. The people and settings recapitulated themselves with energetic variation. The color groupings astonished me: in one cluster, mauves and dusky grays; in another, marine blues and greens that looked electric by comparison.

I hadn’t heard of the artist, who had the rather unusual Korean name of Oh U-Am. Nor did I have a point of reference for his style. His paintings were guileless and skillful at once; the labor in them showed. They took as their subject matter actual slices of Korean history, yet seemed to exist in the timeless space of allegory. I learned from the wall text that the painter was eighty-four years old. He’d been orphaned during the Korean War and had spent three decades as a handyman in a Busan nunnery. He was entirely self-taught.

Who was he? Where did he live? I searched online and found only two photos and a few dated links. I reached out to the curator of the Busan Biennale, Kim Haeju, to learn more. Kim, who grew up in Busan and studied at the Sorbonne, explained that Oh hadn’t painted in earnest until his sixties. He didn’t have identifiable peers or fit into an artistic school. “He’s sort of an outsider artist,” she told me. “The style is somewhat naïve—unstudied.” Oh wasn’t well known, even in Korea, but had shown his work in Seoul many years earlier, at a now defunct gallery called ArtForum Newgate. Kim explained what an adventure it had been to track down his pieces for the show, between Oh’s house, private collections, provincial museums, and his former gallerist’s apartment.

I went to Seoul to meet that gallerist, Yum Hejung. She told me how, around 2004, she got a tip from a prominent art critic about Oh’s work. She went to Busan to court him, and found a sorry sight: he and his wife were living in a ramshackle rental, his canvases and paints scattered about. She resolved to represent him and, after months of coaxing, persuaded him to sell her a painting. She supplied him with oils and canvases and loaned his family money so they could move into a better apartment. In 2006 and 2010, Yum held solo exhibitions for Oh at ArtForum Newgate, titled “The Road” and “Sound of the Whistle,” respectively. The paintings in those shows were sombre in palette and subject matter, focussed on Busan’s past. But a third show, in 2015, titled “Life Is Beautiful,” presented canvases that were uncharacteristically cheery and set in contemporary Busan. The people in those paintings took on a rounder, more individualized cast. It was as though the sun had risen over Oh’s studio.

What happened between the second and third shows, Yum explained, was history butting into the life of a historical painter. In 2010, Korea’s central government informed Oh that his long-dead father had been identified as an anti-colonial activist and would be publicly honored as a patriot. In the late aughts, the progressive President Roh Moo-hyun had expanded a law giving formal recognition and cash benefits to members of the anti-colonial resistance and their descendants. Until then, many such families, including Oh’s, had been red-baited by Korean conservatives. Oh had always known that his father was left-wing and had disappeared in Japanese-occupied Manchuria, but wasn’t sure whether he’d gone there as an independence fighter or a forced laborer. The government’s finding allowed Oh to revise the script of his life and his family’s place in modern Korea. There was also a practical dimension: he would get a small but steady cash benefit every month.

In late November, after the Busan Biennale closed and Oh’s paintings were returned to their disparate homes, I visited him and his daughter, Oh So-young, a retired commercial designer. Oh had moved to an isolated area of Hamyang, in Korea’s mountainous interior, far west of Busan, in 2021, with his wife and So-young. Their son, a professional woodworker, had built them a white, one-story house at the elevated end of a country path. Oh’s wife, who had severe depression, died the day after they relocated, as if to indict the family’s remove from the sea.

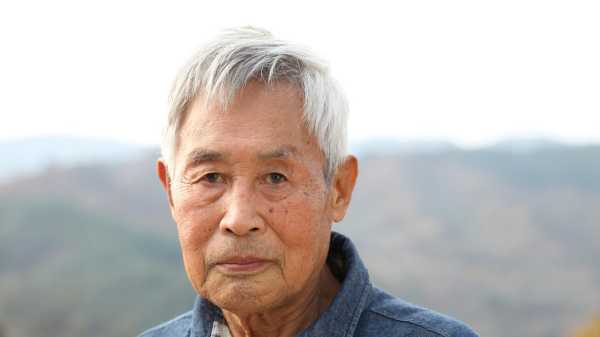

The day I visited, the sky was a clear, cold blue, highlighting the deep orange of the persimmon trees in their yard. So-young was welcoming and voluble in a tunic and loose pants of traditional ramie, dyed violet and black. She cooked us savory specialties from the province of South Jeolla—where her father was born—including an unusual kimchi made of autumnal soybean leaves. Two paintings that I’d seen at the Biennale hung in the entryway of the house: a large canvas depicting a small boy, seen from behind, looking through the fence of a railyard; and a small canvas of a large, angular factory worker, with a collaged advertisement for whiskey. Oh emerged from his bedroom after lunch. He was of average build and wore a denim shirt, cargo pants, and glasses. His hair was white, but his tanned, rectangular face was that of a much younger man; his hands were large and roughly calloused. He talked in short stream-of-consciousness bursts, despite a speech impediment, about his Busan childhood, South Korean politics, and the meaning of individual art works.

Oh U-Am’s paintings are guileless and skillful at once.

At the dining table, we flipped through the catalogues of his three shows at ArtForum Newgate. “This one is no good,” he said, drawing an “X” over an image and turning the page. “This one is fine, I like this one.” Oh has obsessive-compulsive disorder, and tends to paint and repaint the same subjects, on the same canvases, then destroy the ones he doesn’t like. In the move to this house, and many moves before that, paintings and paint supplies had been lost or abandoned. For many years, he had been ill and unable to paint regularly. “I had such severe depression that I wanted to die,” he recalled. “Now I can actually get to sleep without drinking or smoking.” Just recently, he had returned to his easel, making sketches and priming a few canvases that we saw stacked against a wall.

In one new painting, the pastel silhouette of a battle tank was coming into view. “I remember kids throwing rocks at the North Korea People’s Army and climbing up on tanks,” he explained. During the Korean War, Oh’s mother had been kidnapped and killed for serving food to soldiers on the wrong side of the civil conflict. “When I became an orphan, I suffered a great trauma,” he said, motioning to his stomach. He and his two brothers shuffled from place to place, and he managed to attend only elementary school. After the war, he enlisted in the South Korean Marine Corps (“I went because I was getting beat up. I wanted to be feared”), then found work as a resident handyman in a nunnery near Busan. For the next three decades, he drove the nuns around town and maintained the heating system and the garden. “In the boiler room”—where there was surplus enamel paint and wood boards—“sometimes I didn’t have a lot to do, so I began to paint,” he told me.

Oh married and had four children, who grew up on the rambling grounds of the nunnery. He sent So-young, his oldest, to art school for college, and made use of her leftover oil paints and discarded canvases. When she finished school, in the nineteen-nineties, she got a job and set aside her own painterly ambitions. “I realized that he liked painting more than I did, and he was better at it,” she told me. “It was my turn to support the family.” She persuaded her dad to quit his job and devote himself, full time, to his art.

The family struggled to stay housed, while Oh made painting after similar painting. For more than a decade, he fixated on historical events and themes. Oh painted railyards, railroad stations, and the day laborers, street venders, noodle sellers, and club musicians who populated their fringes. “That’s what I saw,” he said. “I’d paint a place and the same place again—but as seen from the back.” He conjured pastoral fantasies, but speckled them with pitiless fact from Korean history. In “Return to Home,” four wintry birch trees flank a country path and a yellow-green sky. A man in a soldier’s uniform walks toward his wife and two young children, but he is less than whole: he leans on crutches; his lower left leg is amputated. In Oh’s largest piece, “Children’s Liberation,” he commemorates the fleeting moment of liberation from thirty-five years of Japanese rule in 1945, just before a national division that would lead to war. An entire town—a Whitmanesque catalogue of mid-century Korea—gathers in a public square. A pungmul folk percussion band plays in full regalia; boys ride bicycles and eat celebratory sweets. “That was when things were still O.K. There was no left or right,” Oh told me. “Only much later did it get bad. They labelled me a Commie.”

Oh’s work after the government awarded his father a patriotic citation, in 2010, shifts toward a brightly lit present. The South Korea of these tableaux is affluent and turbocharged, no longer in a postwar haze. Rail cars and rickshaws give way to cars, buses, and container ships. The human figures, rendered in simple, blocky colors, listen to music and walk little dogs along bustling streets. In paintings of the shoreline, with geographic titles such as “Busan Uryok Island” and “Busan Youngdo Bridge,” tourists and fishermen stand in twos and threes against a background of aquamarine water and triangular dark-purple islands. Cranes and apartment towers pierce the sky.

One of the few Korean art critics to ever address Oh’s work called it Surrealist; another noted stylistic overlaps with Balthus and de Chirico. I’m also reminded of the peopled landscapes of Grandma Moses or Francis Guy. Oh’s conscious influences are more straightforward. He told me that he admires Park Su-geun—a self-taught, short-lived Korean painter, born in 1914, who used Post-Impressionistic techniques to depict traditional life in the countryside. Oh also likes Monet and van Gogh, men who painted their world as they saw it. “No way are my father’s paintings Surrealist. They’re realist,” So-young said. When the three of us looked through his paintings of Busan, she recognized each neighborhood represented, sometimes down to the curve of a street.

Oh portrayed himself on those canvases as well, though never quite identifiably. He is the boy gazing into the railyard in the painting that I saw at the Biennale and in the entryway of his home. There’s also a more recent painting called “The Way to the Library” that shows a solitary figure, also seen from the back, walking up an empty city road. That was Oh, or at least a symbolic version of him, he told me. “I never do self-portraits. You die early if you do.”

The cheeky painting “Immersion” depicts a crowded subway car in which everyone—except for the gray-haired passengers in senior seating—is lost in a smartphone. A red-and-white advertisement reads, “Robo-human fusion surgery.” When I asked Oh what he intended to convey, he said, “I was riding the subway a lot in Busan, because it was free for me, and everyone was buried in their phones. I felt weird for reading a book. I didn’t like that.” His present-day pictures, though optimistic on their surface, contain a trace of loneliness. In the space of a few decades, Oh and his grown children had come to live relatively well, and South Korea had become a wealthy nation. The flip side was a certain alienation: people seemed untethered from one another and their messy, bloody collective past. Only on canvas could he begin to sort it all out. He talked me through some older work: “This was in front of the old city hall.” “This is a colonial detention center for forced laborers.” “This is a police station.” “This is from my imagination.” “This painting is pretty good.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com