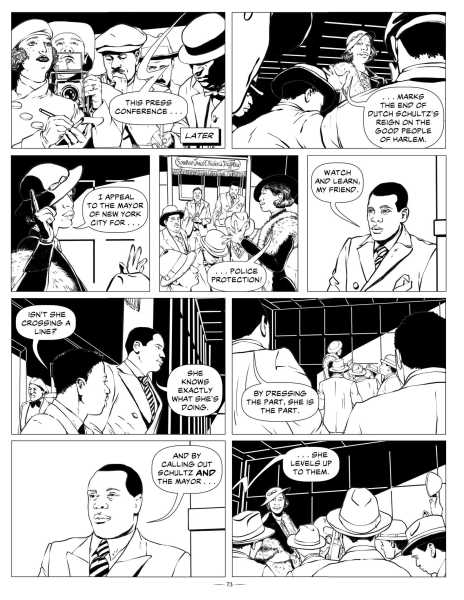

In “Queenie: Godmother of Harlem,” the forthcoming graphic novel co-authored by the writer Aurélie Lévy and the artist Elizabeth Colomba, a vivid but forgotten historical figure is brought back to life: Stephanie St. Clair, or Queenie, a Black female boss who ran an uptown numbers game during the Harlem Renaissance. St. Clair was an anomaly in a business clearly dominated by men, but she successfully carved out a position of power. An immigrant from Guadeloupe, in the West Indies, St. Clair was brilliant and nimble, outsmarting the many systems that made her success so implausible. She continuously called out the corrupt police and government, and advocated for Harlem’s Black community. We spoke to Colomba about her own search for meaningful roots and the process of translating this complex history into a graphic novel.

How did you first hear about the hero of your book?

Stephanie St. Clair entered my life thanks to my mother. She’s from Martinique herself, and she tirelessly advocated for us to know our history and the figures that came before us. Through her, my sister and I learned of Césaire, Fanon, and numerous figures from Martinique who played a role in our culture. At first glance, Stephanie and my mother share only a birthplace. Stephanie was cunning—even ruthless—and a notorious racketeer. However, she was also a powerful Black woman taking control of a world run by men, who refused to let the cards she was dealt stop her from dreaming big and achieving big. I wonder whether my mother felt a kinship with her because of this.

What does it mean to you to amplify a little-known story such as Queenie’s? What do you think is lost when history erases figures like her?

A core part of my practice is dedicated to shedding light on Black figures who have been overlooked or even entirely omitted from historical narratives, and finally rendering them visible. When your history has been erased, how do you learn about your ancestors? How do you learn from the past—let alone determine its effect on our present? How do you celebrate the stories that made you? How do you belong?

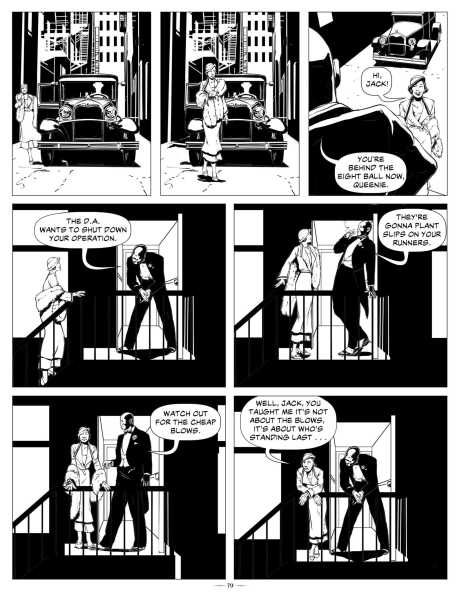

Queenie is not only seldom credited or mentioned, but, as is too often the case, it is a male counterpart whose name we remember: her protégé Bumpy Johnson. Yet it is because of her tutelage that he was built at all. To recenter the spotlight on her—her audacity, her daring, her drive—and reinscribe her into the historical conversation is also to reconnect ourselves to our own cultural footprint.

History should be an objective study, but it is all too vulnerable to ideologies and ulterior motives. Erasing the contributions of Black figures across history only cheats us of the complete story. We all become richer by restoring our legacy.

Your fine-art work reimagines Black people in classical art, often in the eighteenth or nineteenth centuries. What was it like to dive into the nineteen-thirties for this book?

Whether for painting or for this new medium, I take immense pleasure in collecting information. As my writing partner, Aurélie Lévy, and I worked on scenes, we found ourselves checking every single element for historical accuracy: Did cars have a radio? Was this song from this era? Was the subway a possibility?

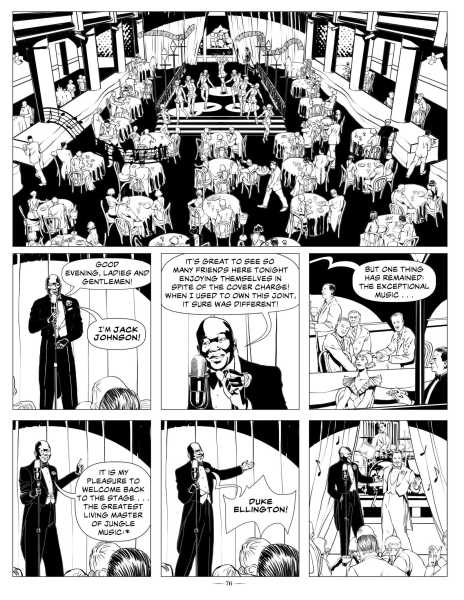

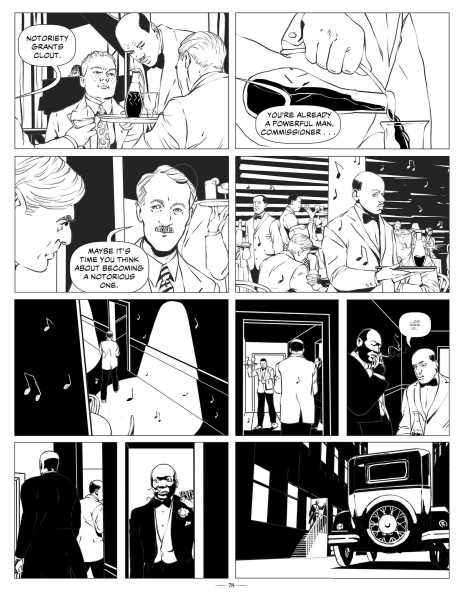

Drawing unveiled yet another level of research and detail, one that I was not prepared for but thoroughly enjoyed. I was able to integrate information and embed it in the story. In one instance, I’d read that by 1933 a board game much like the modern version of Monopoly had just been created. There is a double-page spread in which we introduce Dutch Schultz, Stephanie’s nemesis, who wanted a monopoly on the numbers game in Harlem. As the first encounter with this figure, the pages needed dynamism, and so I used the very same layout of the contemporary game as a visual echo to Schultz’s ambition.

Famous both as a criminal entrepreneur and a fashion icon, Stephanie understood the power of an image and of fashion—I sometimes dressed her in Chanel. Wielding her own aesthetic in the public eye as a strategy of power, she regularly purchased advertising space in numerous publications including the Amsterdam News, curating an image of herself dressed to the nines alongside her critical and exigent writing on civil rights. Likely having seen Coco Chanel in fashion spreads and having been inspired by the designer’s radical social subversion, Stephanie was not only elegant but radiated the authority that such style generates. Dressed by a French name, she would also be directly connected to her roots, which she insistently brought to the forefront in Harlem. I used sources directly from Chanel’s archives, from images of the designer herself to the iconic Breton stripes that she pioneered, and incorporated specific pieces of clothing, jewelled cuffs, and accessories, turning Stephanie into an embodiment of sophistication and power.

Connections like this underline the significance of iconography: whether behind an object, a layout, an outfit, a reflex . . . there is always an additional story.

You, like Queenie, are an immigrant to the U.S. and have chosen Harlem as your home. What drew you to the area, and is there still something special about the neighborhood?

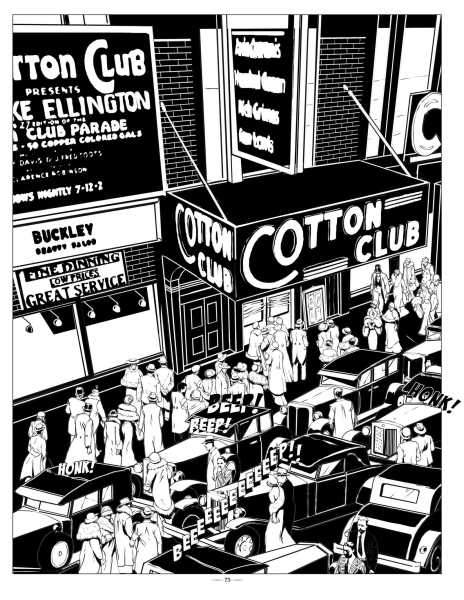

In France, we grew up with two different definitions of Harlem: one version was from the nineteen-twenties, with the glitz and glamour of Josephine Baker, the Cotton Club, and Duke Ellington; the other was the grittier version we saw aired in nineteen-eighties films and TV shows. So I must confess, when I moved to New York, Harlem was not my first choice. But then a collector of mine introduced me to her brother, who made it his mission for me to see the Harlem beneath the movies.

We met at Edgecombe Avenue, where we entered a spacious apartment. Inside was a band playing jazz, and numerous chairs laid out through the rooms and the hallway. It was packed. Full of people of all ages and ethnicities. An elegant, elderly Black lady was passing orange juice, water, and some cake on a tray. You could make donations or simply enjoy. The energy was palpable. If you could sing or play, you were invited to jam. This was a “rent party.” It was inviting, warm, and unique. Here, I could pursue my practice. At that moment, I was able to call Harlem home.

Despite gentrification, these worlds still exist. There is the occasional cookout on the sidewalk in the summertime, the braiders on 125th, the line up at the Apollo—all in the midst of slick new condos. Harlem is a place that I continue to thank for the inspiration it gives me. Taking the A train made famous by Duke Ellington, and walking the streets of James Baldwin. Here, I continue to be a storyteller.

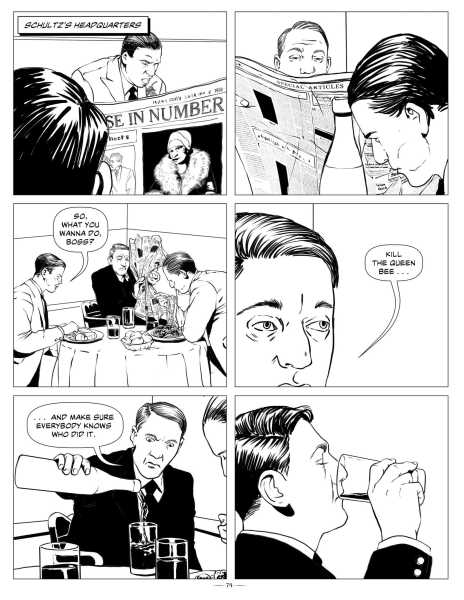

In the excerpt below, Queenie contemplates retirement with her friend and mentor, Roz, while Dutch Schultz, a mobster, hatches a sinister plot against her.

This is drawn from “Queenie: Godmother of Harlem.”

Sourse: newyorker.com