Isaac Childres was thirty-two years old when he started designing what is widely considered the best board game in the world. In 2015, he was living in Lafayette, Indiana, with his wife, Kristyn. Childres, who has a slight and somewhat owlish figure, and the squint of a medieval illuminator, had recently completed a Ph.D. in physics at Purdue University. He wanted to make a board game that felt like an adventure, with numerous stories and locations to explore. There would be thieves, magic spells, and a character made from a swarm of bugs. Childres also sought to “minimize randomness” and avoid any dice.

In September of that year, he unveiled Gloomhaven, a Brobdingnagian fantasy game that fit inside a twenty-two-pound box the size of a microwave. Childres’s business model was more Tesla than Parker Brothers: he listed the Gloomhaven project on Kickstarter, using preorders to gauge interest and bootstrap production. Buyers were attracted by the scale of the experience, its imaginary world, and especially by Gloomhaven’s so-called legacy components: as the story goes on, players unlock new characters, tear open secret envelopes, and apply stickers that permanently transform the map board. There are dozens of possible play sessions: each of the game’s ninety-five scenarios is a unique quest that can take hours, where everyone works together to slay monsters, solve puzzles, and collect treasure.

Serious board-game players are a culture unto themselves. They favor novelty over tradition, mechanics over aesthetics, the ingeniousness of a puzzle over immediate ease of play. Enthusiasts open their own cafés, stage their own conventions, and invariably log into a Web site regrettably (but fairly) named BoardGameGeek. B.G.G. prizes its ratings system, wherein players evaluate products on a scale of one to ten. These scores—as well as a game’s recent popularity—lead to a ranking, updated nightly. Monopoly, which has an average rating of around 4.3, is ranked in the middle twenty-three thousands. Chess stands at four hundred and thirty-five. (All ratings are current as of the time of publication.) Enthusiasts scrutinize B.G.G.’s top five spots as closely as the N.B.A. draft, and in the first seventeen years of the site only six games had ever ascended to No. 1.

Gloomhaven would become the seventh—a title it has held for an astonishing five years. Childres’s game incorporates about seventeen hundred cards, four hundred cardboard tiles, eighteen sculpted heroes, and zero dice—all of which he presided over alone. He did not meet—and scarcely even spoke—to the game’s principal artist (living in Ukraine) and its sculptor (in Canada), its map guy (in Spain), distributor (in Fort Wayne), or manufacturers (in China). While Kristyn went to work at her office, Childres stayed at home, typing away on a wireless keyboard. At the end of the couch, the couple’s pet Yorkie would sit licking a toy.

The Yorkie’s still around—her name is Millie. So is the Ukrainian artist, Alexandr Elichev, painting skeletons and sorcerers as a war rages above his head. During the past seven years, Childres’s company, Cephalofair Games, has sold more than half a million copies of Gloomhaven and grown to have four full-time employees. In October, 2021, Isaac and Kristyn moved from Indiana back to California, where Childres is from; in May of this year, they had a baby. When we spoke this summer, the company was a year and a half late for the release of Gloomhaven’s sequel—possibly the most anticipated tabletop game of all time—and Childres didn’t own an actual table. As he explained, “We have, like, a nice countertop.”

Childres grew up in Bakersfield—pistachio country—the youngest son of a schoolteacher and an architect. His parents have been members of the same Baptist church for forty-three years, and much of Isaac’s childhood was spent in the orbit of its congregation, including going camping with the members of Selah, his mother’s praise and worship band. “He was always observing,” Virginia Childres recalled. Whereas Isaac’s older brother, Joseph, was exuberant and creative, Isaac skewed arithmetical. At age two, Virginia claims, he could complete a hundred-piece jigsaw puzzle. At the grocery store, he would track the prices of the items in their cart. Even as a toddler, Virginia said, Isaac “wanted to do things perfectly the first time.” Before Isaac entered a room to talk with his family, his mom once heard him practicing conversations with his cat—delivering full sentences while he thought that he was alone.

The Childres family only occasionally played board games—friendly bouts of Yahtzee (B.G.G. rank: 23,215) or hard-fought games of Risk (B.G.G. rank: 22,713), in which Isaac locked horns with his dad. Video games such as Super Mario and Phantasy Star loomed more largely in Isaac’s early imagination, together with Choose Your Own Adventure books and sagas dreamed up with Joseph—first in Lego and G.I. Joe sessions, and later as stand-alone stories. In high school, Isaac made a “conscious decision” to become less introverted, according to his mother, and branched out from his bookish interests (math, science, chess, perfect classroom attendance) into very slightly less bookish ones (school newspaper, literary magazine, playing Oberon in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”). He also started playing Dungeons & Dragons with his friends, once his mother was convinced that “he wasn’t going to become a devil worshipper.”

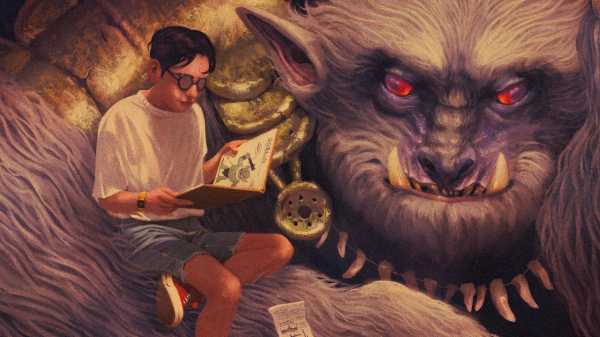

Illustration by Dexter Maurer

When it came time for college, Childres told me that “the most important thing was being able to pay for it.” He accepted a full scholarship to the University of Oklahoma, where physics-department classmates introduced him to modern strategy games like Settlers of Catan (B.G.G. rank: 473). By the time Childres reached grad school, he was hosting his own board-game nights, and, when one of his roommates discovered B.G.G., they set out to try every game in the top five. Soon Childres’s interest in gaming was consuming his life: “It was taking Isaac forever to finish up his projects for his doctorate,” his mother said, “and then I found out it was because he was working on this board game.”

As a teen-ager, Childres had been drawn to physics for the way it made mathematics tangible, applying raw numbers to the real world. After reaching Purdue, where he studied radiation effects on graphene, he grew disillusioned. “The farther you go, it’s less math, and more just running experiments over and over,” he said. He bought a secondhand Yamaha Virago motorcycle (“I think I was mostly interested in the fuel efficiency,” he claimed) and met Kristyn on OkCupid, taking her for a ride on their second date. Krisytn told me, “I would look at Isaac in the evenings sometimes when he was playing games, and I’d think, He’s so smart—it kinda sucks that he doesn’t love what he’s doing.” Childres bought the domain cephalofair.com—a misspelling of “cephalophore,” the word for a Christian saint who walks around carrying his or her own head—and started blogging about his ideas for a video game.

Impatient for new challenges, Childres auditioned twice for the reality TV show “Survivor” and, in 2013, the TBS series “King of the Nerds.” For the former, Childres, a longtime vegan, offered to go back to eating meat. In an audition video for the latter—which is still online—the then thirty-year-old academic can be seen stripping off his T-shirt to show his pallid “nerd physique.” The producers eventually requested footage of Childres’s dance moves—“They sent back the message ‘LOVE,’ ” Kristyn said, “and then we never heard from them again.”

By then, Childres was working on Forge War, what he calls a “Euro-inspired blacksmithing and dungeoneering” game, the premise of which he hammered out while sitting in the back of a physics-department meeting. In June, 2014, Childres took his game public, launching Forge War on Kickstarter, and, although the game’s success was modest—it would eventually peak at No. 757 on B.G.G.—the experience emboldened Childres to make his hobby full time. He and a friend, Clinton Bradford, would regularly make the one-hour drive from Lafayette to a house in Carmel, Indiana, where they playtested prototypes with other board-game designers. “One day, we were supposed to play something else, but Isaac was, like, ‘I just thought this up, I really want to try it instead,’ ” Bradford recalled. With handmade cards and components scavenged from the board game Mage Knight, Childres demoed his Gloomhaven play-concept. “Right away, we could tell it was going to be pretty good,” Bradford said.

In January of 2015, Childres reached out to Elichev, an illustrator he had found on the digital-art Web site DeviantArt. He was only looking for Gloomhaven’s cover image at first; in exchange for a few hundred dollars, Elichev turned in a nectarine-tinted painting of mysterious figures walking through a fantastical medieval bazaar. That image, and others Elichev subsequently created, formed the banner on Kickstarter under which Childres proposed his vast and elaborate game, then half-completed. Only about five thousand people initially placed orders, but when those games finally shipped, in early 2017, positive reviews flooded in.

It would be easy to credit this reception to Gloomhaven’s scale and theme: best-selling tabletop games like Dungeons & Dragons have proved there’s a market for complicated fantasy epics. But Gloomhaven’s secret weapon is the mechanics of its game play, and Childres’s greatest gift is his mastery of chaos. Many sophisticated players prefer board games with relatively little randomness—chess, for example, is held in much higher esteem than Hungry Hungry Hippos (B.G.G. rank: 23,458). However, randomness can also give a game a sense of fizz, or peril. Gloomhaven strikes an unusually satisfying balance between intention and accident: it’s deeply strategic, often much more strategic than a rambling session of D. & D., but bristling with (un)lucky breaks and chance discovery. Choices feel meaningful, yet the game has its own scampering rhythm, too. “It hits a really good groove,” Bradford said; players may not be troubled by what’s known, disapprovingly, as “analysis paralysis.”

Encouraged by word of mouth, and, despite—or because of—Gloomhaven’s limited supply, demand for the game soon soared. When Childres finally announced a second printing, in April of 2017, forty thousand new backers pledged a total of almost four million dollars. The following month, while Isaac and Kristyn were at a party hosted by one of her college roommates, Isaac checked B.G.G.’s leaderboard on his phone. When Kristyn glimpsed the news, she started singing a line from the Drake song “Grammys”: “Top five / top five / top five!” Before the end of the year, Gloomhaven would be No. 1.

“I hate capitalism—I guess we can start there.” I spoke to Childres over Zoom, on which he had the frayed tone—and rumpled look—of a work-from-home father to a three-month-old. “I’ve never approached my business from a perspective of, like, ‘Let’s make as much money as possible.’ I think it’s the root of pretty much all the problems of our society.” Early on, the designer made it easy—and legal—for fans to create their own custom content for the game; one of these, an ambitious not-for-profit expansion called Crimson Scales, has raised more than three hundred thousand dollars in crowdfunding. Childres himself has only released one small Gloomhaven expansion, one adjacent tile-placement strategy game, and, finally, Jaws of the Lion, a simplified version of Gloomhaven aimed at those who might be intimidated by, say, an eighty-page rule book. It’s been a success—selling nearly as well as the original—but it hasn’t been as profitable.

In December of 2019, Childres announced Gloomhaven’s official sequel: Frosthaven. It is roughly the weight and height of an Icelandic sheepdog—around fifty per cent longer and fifty per cent heavier than its predecessor, and requiring about three hundred hours to complete. In ten minutes, Cephalofair received five-hundred-thousand dollars’ worth of pledges; after a month, Frosthaven’s Kickstarter campaign had raised a total of thirteen million dollars from more than eighty-three thousand backers, making it the most successful crowdfunded board game of all time.

Frosthaven was originally projected to ship in early 2021. Childres’s design team adapted easily to the pandemic, moving playtesting sessions to a popular online board-gaming platform, but things weren’t so easy for Cephalofair’s chief operating officer, Price Johnson, who described COVID-era manufacturing and fulfillment as “the ultimate game of boats and roads.” The Shanghai region, where most of Frosthaven is produced, has slipped in and out of lockdown. “You get delayed a few weeks here and there, and suddenly you’re behind by a year and a half.”

With Gloomhaven, Childres had taken pains to offer strong, realistic portrayals of female characters, and Elichev’s illustrations largely eschew high fantasy’s typical catsuits and cleavage. But over the following few years, especially after the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, Cephalofair had been accused of reinforcing real-world prejudice with certain of its imaginary species. The Inox, an ox-like “primitive and barbaric race,” invokes Black and Indigenous stereotypes; one Reddit user described the Quatryls as “the yellow skinned short people who are good at building technology with there [sic] delicate fingers? The ones with the unusual eyes who hail from the eastern continent, and are ‘encouraged to study as much as possible’ from an early age’? Those quatryls?”

That summer, Bradford confronted Childres (as he had before) about the unconscious racism he saw seeping into his friend’s games. This time, Childres, who is white—as are Bradford and Cephalofair’s entire team—was receptive. “For a long time,” Childres explained, “I had the mentality, Oh, this is fantasy. It’s not the real world. I can just do whatever I want.” He would eventually publish a lengthy mea culpa, resolving to do better with Frosthaven and announcing the hiring of a cultural consultant named James Mendez Hodes. This post drew more than a thousand responses, some of them angry—accusing Childres of pandering to a “church of wokeism” that “has no place” in board games.

Mendez Hodes, who is of European Jewish and Filipino descent, originally gained notoriety with a series of essays about the racist implications of fantasy orcs. Gaming companies like Jackbox Games and Wizards of the Coast soon hired him to vet their in-game lore. “I remember thinking, I wish I could just tell people they were racist for a living!” he told me. “And it turns out I can.” Mendez Hodes doesn’t believe gaming has a particular racism problem. “I’m sure there are toxic knitting circles out there. The problem isn’t the yarn,” he said. Still, nerd culture “privileges intelligence as if it’s inherently valorous,” he argued, and it excuses even very bad behavior if—like Elon Musk—the person is considered sufficiently “smart.” Meanwhile, as Mendez Hodes put it: “Twitter is imploding in slow motion and Teslas are exploding on the road!”

Mendez Hodes spent about thirty hours reviewing Frosthaven’s text and images. He started with the “easy stuff”—replacing problematic words like “tribe,” “exotic,” and “shaman”—and flagging situations where players were forced to reproduce real-world oppression, like misogyny or xenophobia. There were also places where Childres had again fallen into stereotypes: the yeti-like Algox, for instance, conjured the timeworn “noble savage.” According to Mendez Hodes, the details that make up every fantasy species—and every individual culture within that species—should be informed by the environments in which they live. It was also important that Frosthaven’s various “sapient” peoples have the chance to be centered in the game narrative, and not just passively “saved” by the heroes. Take the example of the Lurkers, a crab-like species that features prominently in the story. “We wanted them to seem like more than crabs,” Mendez Hodes said. “To seem like crabs who could . . . plan a rave.”

When asked about all these course corrections, Childres said, “You’re not perfect. You don’t have complete information. Sometimes you need to listen to other people, and change.” As Childres introduces Frosthaven to his waiting fans, he’s learning that even the most calculating board-game players can be surprised—or even upended—by a move. Frosthaven is dedicated to Isaac’s older brother, Joseph, who died two years ago in a drug-related accident. Childres lives closer to his parents now; sometimes he takes his kayak to the ocean and hopes to see an otter. It is difficult to minimize randomness in a life on this Earth—but you can adapt to it, take steps. Frosthaven started shipping earlier this month; on B.G.G., it had an initial rank of 4,034. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com