Seven years ago, the filmmaker Rian Johnson was chosen to write and direct “Star Wars: The Last Jedi.” He was a surprising pick for what was, alongside Marvel, arguably Disney’s biggest film property. Johnson had made his name writing and directing the low-budget noir film “Brick” and the sci-fi thriller “Looper,” which were both quirky and critically acclaimed, and he exhibited an obsessive familiarity with their respective genres, coupled with a desire to cheekily reinvent them. “The Last Jedi” was, predictably, a blockbuster, and the best-reviewed film of the most recent trilogy, but some fans objected to its departure from typical “Star Wars” fare in its storytelling style and unique sense of humor. (Ironically, Johnson is a lifelong “Star Wars” nerd and superfan.) After the film’s release, Johnson, who is now forty-eight and lives in Los Angeles with his wife, the film historian and podcaster Karina Longworth, moved on to other projects.

It turned out, however, that franchise blockbusters were still in his future, but not in the way he was expecting. After “Star Wars,” Johnson had decided to transition to a genre that had always fascinated him—the whodunnit—and the result was the 2019 film “Knives Out,” which merged his sense of humor, his progressive politics, and his love of mysteries into a smash hit. Johnson spent the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic writing a follow-up: “Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery,” which will open in select theatres for exactly a week, on November 23rd, before migrating exclusively to Netflix, which reportedly paid more than four hundred million dollars for the movie and its eventual successor.

Like the original film, this one stars Daniel Craig as Benoit Blanc, a fictional famous detective who will be assigned a new mystery to solve in each “Knives Out” installment. “Glass Onion” is set on a Greek island where a billionaire, played by Edward Norton, has invited a bunch of old acquaintances—numerous eccentric figures embodied onscreen by Janelle Monáe, Kate Hudson, and other stars—for an unknown reason. Soon enough, Blanc, who also received a mysterious invitation, is trying to solve a murder. Critics and audiences embraced the original “Knives Out” as the type of film that one doesn’t get to see enough of anymore: dialogue-driven, FX-less, intelligent entertainment. (The first film is said to have cost only forty million dollars to make.) This one comes with loads of celebrity cameos, and also even more political commentary than the first one, which functioned as a spoof of wealthy, and seemingly Trump-supporting, murder suspects.

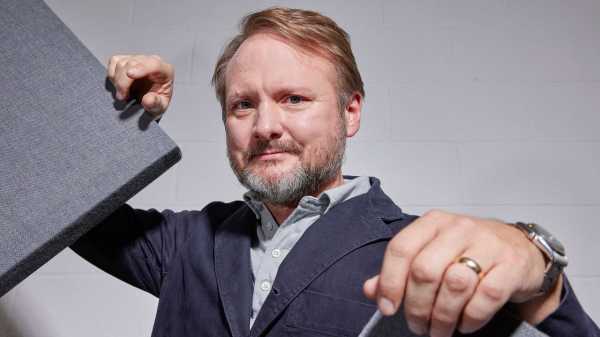

I recently met Johnson at his workspace in Los Angeles, which has the feel of a tech company, with an open layout, visible (albeit minimal) snacks, and glass doors. Off to one end is a small screening room; on the other end is Johnson’s modest office. He was dressed casually when I arrived, and has an inviting, laid-back manner. It’s somewhat hard to envision him ordering around actors, but he listens attentively and makes constant eye contact. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity. In it, we discuss what he learned from Steven Spielberg about directing, his obsession with whodunnits, and how Netflix is apparently able to spend so much money.

There were a lot of COVID and mask jokes in the movie.

That’s because I wrote it in 2020. It’s probably also why it’s set on a Greek island.

What was it like filming a movie when COVID was worse than it is now?

It’s so much harder directing with a mask on, just because so much of directing is performing, in a weird way, and being an audience for the actors, and when you lose that ability it becomes a lot harder.

I read that you once said that you decide on a project by first deciding on a genre.

That’s the first starting point. More often than not, it’s a genre that I’ve had some emotional connection to. So with whodunnits, I’ve been an Agatha Christie fan since I was a kid. With “Star Wars,” obviously that was its own thing, and with “Looper” it was science fiction, so usually it’s something that I’ve got deeply rooted feelings about. It’s a combination of that and something that I want the movie to be about for me. Something I want to work out or wrestle with in making it. That’s the combo that gets me started.

My memory of Agatha Christie was that the mystery was a huge part of her work, whereas, with “Knives Out,” I’ve always felt like what you’re really interested in is less “Who did it?” than the other stuff.

Yeah. But, as a big Agatha Christie fan, I don’t think that’s entirely true, because I think she was a great storyteller, and I don’t think great storytelling happens from figuring out who has done it. I think that’s just her creating good characters and dramatic situations. I think she very often gets simplified in the culture in the way people think about her work. So I always find myself getting a little defensive. [Laughs.] She was doing what I describe myself as doing with genre, which is placing the whodunnit as a shell over other genres. “The A.B.C. Murders” is really a serial-killer thriller, and “And Then There Were None” is a slasher movie.

The thing that got me going on wanting to make “Knives Out” was setting it in modern-day America and not being afraid to set it in modern-day America and to engage with the culture of today. Christie did the exact same thing. Her books weren’t period pieces; they were very much engaged with what was going on at the time. And, in a way, it’s a very traditional, conservative form of storytelling, where chaos is created by a crime and the paternal detective sets everything right by the end of it. And so, using that again as a shell, what can we put in here that’s actually interesting to look at and talk about?

Did you always think that you wanted to tell stories via movies?

As soon as I knew that was a job you could have. I was one of those kids who just had a camera in my hand. I started making movies in junior high. I got a Super 8 camera, and then had video cameras and was making movies with my friends through high school. I read a book about George Lucas, and he talked about how he’d got into U.S.C., and that was when I realized, Oh, maybe there’s actually a path to doing this for a living. But I was always writing and telling stories, and movies were predominant because of being a kid in the golden Amblin age.

Did you ever want to write separately from movies?

Yeah, and that was the other thing I was doing all through high school: writing stories. Writing was always separate from when I made movies as a kid. And so it wasn’t until I really started thinking about features that I started putting those two together.

When you’re writing and directing a movie, does it change the nature of writing? Are you picturing how you’re going to film a scene?

There’s a million ways to skin a cat, but, for me, I’m absolutely seeing the movie in my head. I’m a really structural writer and I spend a massive amount of time at the beginning outlining, and I need to really know what the movie is, down to a scene-by-scene breakdown, before I start typing. Otherwise, I run out of gas quick. I will spend eight or nine months just working in little Moleskine notebooks, just diagramming out. And then there are the last couple of months, where I panic and realize everyone’s waiting for the script. But, at that point, the actual writing of the script can happen very quickly, because you have the movie in your head.

And you found Robert McKee helpful in this?

My dad wasn’t in the film business at all. He was in the homebuilding business, but I think he was always frustrated. He always wished that he could have made movies. So he was trying to write a script and he went to one of McKee’s seminars, when I was in high school, and he took me along to it. I feel like everything I know about structure and about what structure actually means in terms of storytelling was planted.

What do you think that people who don’t like McKee or his methods are critical of, and why do you think that they’re wrong?

Well, the common perception is that it’s dogmatic, that it’s formulaic. It’s not about organic storytelling or about emotion but it’s about “You have to hit your inciting incident by page 30, and you have to do this by this.” I find him to be the opposite. He describes principles in terms of why structure works. It takes a specific type of engineering to keep an audience entertained, in the dark for two hours, as opposed to a novel. It’s really about just the discipline of keeping the audience interested. That, for me, is the real benefit of structure. And breaking it down into sequences that can maintain an audience’s attention, that overlap with each other, so it’s like Tarzan swinging from vine to vine—that’s just for the way my brain works.

Is there a way in which you’re interested in toying with ideas of masculinity in the lead character of “Knives Out”? I don’t want to reveal any spoilers here, but . . .

Oh, yeah. Absolutely.

And you cast James Bond.

Absolutely. There is also very much fun in finding who this person is, and kind of shaping it in a way that might be against some people’s expectations.

My sense of Daniel Craig from interviews is that he is interested in playing with that image in some way.

That’s a good characterization. I mean, I don’t want to speak for him. And I think, first and foremost, he’s just interested in doing interesting things. And I think that was maybe the appeal of this more than anything else. It’s not, like, “Oh, let’s mess with the Bond image.” It was “This will let me do something totally different, and this will let me zig as opposed to zag.”

Tell me what got you into doing some episodes of TV, and how you got hooked up with “Breaking Bad,” where you ended up directing arguably the series’ most famous episode, “Ozymandias”?

Vince Gilligan apparently saw “Brick” and just got in touch with my agents. I think they had just done their first season. I wasn’t familiar with the show. Luckily, we got back in touch in their third season, when they still hadn’t completely broken out yet. And I remember being on set at the time and there was a real feeling of a little-brother-type thing with “Mad Men.” And I remember just saying, “Yeah, yeah, this, it’s going to break out.” Thinking back, just to see that weird indie movie and then to reach out to the director, and knowing all the hoops you have to jump through to get directors approved, it makes me even more grateful.

How different is it to do an episode of a TV show that’s already been established, already has a visual style, already has a thematic style, has a showrunner, etc.?

I loved it. I loved it. I slightly distrust anyone who claims to enjoy writing. Directing is the fun part, definitely. And so to just have a great script put in your lap, and then to go and direct great actors doing it—yeah, it was like heaven.

Is that something you think you want to do more of, directing other people’s writing?

No.

So you like pain and suffering?

I love pain and suffering. You know, you hate it but you love it. And also just to have—at least for however long I’ll have it—the opportunity to get my own stuff made is a real privilege. I feel like I should make hay while the sun shines. And it’s funny, though, you’re asking how is the experience different? It is different, but it’s also weirdly the same, because there’s a strange thing that happens. I don’t know how to describe this without sounding crazy, but it really is like you switch to being a different person when you’re the director, and all bets are off. And, whatever that idiot wrote that he thought was going to work, it doesn’t matter if the scene’s not working, and you’ve got to just throw it out.

“I never saw directors and thought, I want to be sitting in that chair,” Johnson says. “If anything, that seemed kind of terrifying to me.”

When you were a kid, how romantic was your notion of moviemaking and being on a set?

I never really romanticized the notion until I got to film school and started learning about John Huston and all the great grand men who made movies.

It didn’t seem so fun to be on set with John Huston.

It doesn’t, and yet that’s what you romanticize. A friend of mine, Scott Frank, says that there are people who like being directors and there are people who like directing, and I think, just in my heart, I do just like directing. I never saw directors and thought, I want to be sitting in that chair. If anything, that seemed kind of terrifying to me, because I was very just socially awkward.

Have you got to meet the filmmakers you looked up to?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. It’s nice because I feel like I never had a mentor the way I craved one when I was actually coming up, in my twenties and thirties. Meeting Spielberg recently and meeting Frank Oz, and actually becoming friends with Frank Oz—Frank is a terrific director and he is a director whose movies I actually really loved. And when he played Yoda, in the “Star Wars” movie, there were weeks and weeks and weeks of prep with him for all the puppet stuff, and we ended up getting close. That kind of actual relationship where you can actually talk to somebody about stuff and your insecurities.

What did you want a mentor for in your twenties? More for pragmatic advice, or for emotional support?

All of that. It’s just looking for that fatherly help. It’s tied up in both the pragmatic “God, it would be nice to have some help” and in that deep-rooted young-man-looking-for-an-older person’s-approval [situation].

What was your meeting with Spielberg like?

I’d met him a few times during the course of “Star Wars,” and he was really generous and came in and watched a cut, and we talked a bit about it. But with “Knives Out” I had lunch with him and got to have a good conversation with him. I felt bad because I just asked him movie Q. &. A questions. How do you block a scene? That’s something that I had just been thinking a lot about, and something he’s specifically a master at is blocking and staging, and so I feel like I probably assaulted him with questions. He was very patient.

When you think of him and blocking and staging, what comes to mind?

All of his stuff. When I started making movies, I was thinking in terms of shots and I was thinking in terms of what the camera does. Recently, especially making these ensemble pieces where you have seven or eight actors in the scene talking to each other, I’m realizing more and more that it’s not about shots; it’s about staging and blocking. It’s about who’s where in relation to the camera, how they move, and how that turns into a different shot. Spielberg’s a modern master of that. It’s, like, Spielberg and Michael Curtiz. Steven Soderbergh recently did that thing where he turned the “Raiders” footage black-and-white and dropped the sound and just played the scene where Indy’s packing to go on his adventure. It’s very interesting because it’s a one-er that you don’t realize is a one-er when you’re watching it, because it’s so artfully done. You suddenly realize when you’re watching it without the dialogue and without color, and you just see the graphic elements of it: the depth he’s creating and the frame, but also how the camera will shift three feet here and suddenly it’s an entirely other, brilliantly staged shot. It just keeps evolving.

It’s interesting that you said Michael Curtiz, because there’s stuff in “Casablanca,” at the café, where there’s so much going on and you still know where everyone is.

You are completely oriented. He’s also always creating shapes with his blocking, in terms of foreground, midground, background. There’s always something that draws your eye from one to the other, and you always know where to look. He’s always creating interesting shapes and doing the thing that classic Hollywood had the guts to do, which is letting a dialogue scene play out with four people in the frame and not popping into closeups until they really had to. Which Spielberg does.

I would imagine that it would be weird to get a compliment from Spielberg. Do you compliment him back? “Oh, you know, ‘Jaws’ was really suspenseful.”

It was. [Laughs.] “ ‘E.T.’: Well done.” His work is important. Just personally to so many of us and on such a deep level. It’s hard to even parse, but he’s also just such a cool, unassuming guy.

I don’t want to ask a lot of “Star Wars” questions, since I know you’ve talked about it in other interviews.

Ad nauseam. [Laughs.]

The reason—

No, I love it. I do actually love talking about it.

It was interesting to me that, given the way you were talking about genre, what people got angry about was that you’d not done a “proper” “Star Wars” movie. The complaints ranged from really offensive stuff, like complaints about a female protagonist, to criticism about the way that Luke was written and portrayed. Was that something that was particularly painful for you?

No. And, when I read what those people were actually saying, I was, like, “Oh, I completely disagree with this.” They’re wrong. For me. Everybody can like whatever they want and not like what they want. And “Star Wars” fans, in particular—growing up as one, arguing about other people’s opinions being wrong is sort of the bread and butter of it all. I didn’t feel crushed. Like, “Oh, no, I didn’t make a real ‘Star Wars’ movie.” I felt, like, “No, I did.”

Did it change your relationship to the series, though? Your emotional relationship to being a fan with the series?

You mean the whole process of it? I mean, yeah, you’re going to come out the other end different.

Could you go see another “Star Wars” movie . . .

Oh, my God.

. . . at the theatre and feel the same excitement, or whatever else?

Oh, fuck yeah. Yeah. My God. Yeah. In terms of that, I think I love “Star Wars” even more now. I think what actually frustrates me is people’s perception that I had a negative experience somehow, or people’s perception that it was somehow a traumatic experience, or something. The reality is that it was a completely joyful experience even through the back end of it, the past few years, the reception of it.

When “Knives Out” was a big success, people talked about it as a mid-budget movie that did really well with no special effects and no superheroes. Did you set out consciously to make a movie like that?

No. I’m aware of that, and that’s nice, but that was never at the heart of why I set out to make it. No, in a way, if anything, I think that, because we were coming right out of “Star Wars,” I felt a slight pain of “God, am I spending the juice of coming off a huge thing on something kind of small, intimate?” I knew that it was the next thing I wanted to do. I knew why I cared about it. I knew why I was excited about making it. The things you’re describing: they’re things that you talk about with filmmaker friends over dinner after the movies come out, or something.

When did you first think about Daniel Craig for the lead role?

It was in the casting. I wrote the script just having no idea who it was going to be. Actually, when we started casting, Daniel wasn’t available. He was, like, one of the first people we asked about, and he was off the table because of James Bond. There was something that happened and they were delayed, basically. It was incredibly late in the process that he even became a possibility. The instant he did, we got him the script.

When you say he was a possibility, he hadn’t read the script?

Oh, no. He hadn’t at all.

So you were just talking and saying that he would be good. Well, what was that process?

This was a little specific, because we knew we needed a movie star. We knew that we needed somebody who—not just for financial reasons, although also for those—was going to have that kind of gravity on the screen and was going to have that kind of magnetism.

We needed somebody who was the sun in the center of the solar system, and there are not many of those people, and they’re all busy. It’s kind of like the housing market in L.A., trying to cast movie stars these days. There’s a lot of work and not a lot of houses.

The Bond franchise is zoning laws, yeah.

Yeah, exactly. Precisely. They’re very strict.

When you finally got Daniel Craig the script, what did you hear?

I was on vacation with my wife, and I actually felt like James Bond. I had to get on a motorboat to leave the resort we were at, to go to a plane to fly to meet Daniel. We were in the Caribbean and Daniel was in upstate New York. I flew, and it was wild. I just got off the plane and drove directly and met him at a café. We ended up spending the afternoon together and talking about it. Then I flew back to finish my vacation.

How did your wife deal with this?

She was very, very—

Supportive?

Supportive. Yeah, very. At that point, it was so late in the game, we actually weren’t sure whether we were going to make the movie next. From the instant Daniel signed on, it was so quick. I think in a couple of months we were shooting the movie.

So the movie came out, and it was a hit. And then when was there talk of follow-ups?

Well, we were talking when we were on set about “Boy, it’d be fun to make more of these if people end up going to see this.” And [I was interested] for the reasons I described earlier—in terms of what was exciting to me about the murder mystery as a genre being this constantly reinventable form combined with the ability to be very, very current with it in terms of its engagement with the culture.

But the idea was to do more installments with only Craig?

Hundred per cent.

Everyone else would be new in the follow-ups?

Yes. In my head, it was: This is not going to be a sequel to “Knives Out”; this is going to be another Benoit Blanc case. And I feel like there’s so much gravity right now toward world-building and toward mythology of characters and building out backstory and all of this stuff. And I feel like trying to push back on that and say, “No, let’s come up with fun, new stand-alone things every time.” That feels more creatively interesting to me.

How did you decide to go with Netflix?

Well, they came in after I had written the script. So, creatively, it didn’t end up changing anything in terms of what the movie was. We had had a great experience with Lionsgate, but our deal with them was just for one movie. And so we were just, like, “Let’s kind of test and see what’s going on out there. And so we put it out there and they made us the offer, and it was very evidently the right thing to do.

Do you feel like you understand the economics of it from their perspective?

I don’t know if anybody understands the economics.

I remember reading about it and thinking, This is a lot of money. . . .

The way it makes sense is assuming this is going to be a movie that does what the first one did—and, as opposed to this payment and that payment down the line for the lifetime of the movie, it’s doing it all at once. If you do that and actually do the math, it does start to make some kind of sense.

So it’s not like you’re going to be getting checks in ten years because this movie’s going to be on TBS.

This is it, man. No. The check is cut.

Does the idea of people watching it in a theatre not matter to you?

Yeah, absolutely.

So did you have some conversation with Netflix?

We had lots of conversations. It’s a tricky thing; I’ve talked to filmmaker friends who are making movies for streamers, and the reality is that more people are going to see it streaming than ever will see it in the theatre. But, at the same time, it feels so important to me, especially for a movie like this that’s meant to be a crowd-pleaser and a communal experience in the theatre.

I remember going to see the first one at a sneak preview, and people were going crazy. I just watched this one by myself, and it was a really different experience.

Absolutely. It’s engineered to be seen with a crowd. And to me, also, I feel like that’s why the first movie caught on, with people seeing it with a crowd and then coming back with their family.

Did you and your wife bond over movies? [Longworth was a film critic before hosting the podcast “You Must Remember This,” which covers stories from Hollywood history.]

We first met when she was still a critic, ten, eleven, twelve years ago. Geez. But, yeah, our first connection was Film Twitter, I guess. And I feel like it’s pretty great with our relationship, because we do have very similar interests but do very different things in that field. And also it’s pretty incredible having a film historian who’s constantly doing research as a wife. There’s always a movie that she has to watch for work that I get to; it’s like living in film school. It’s pretty amazing.

This is the happiest Film Twitter story I’ve ever heard.

It can happen, kids. Keep believing, keep tweeting. That’s the lesson. Keep tweeting.

Keep tweeting at female film critics all the time.

Exactly. Because they will marry you, eventually.

I want to ask you about politics and movies, because it was definitely a theme to the first “Knives Out,” and is definitely one in this installment. Is that something that you’ve wanted to smuggle into your movies? It’s not necessarily part of the genre.

I talked a little bit about Agatha Christie engaging with the culture. She never really got political, though.

Racism is not political?

[Laughs.] I don’t know. I feel like, especially since 2016, the personal and the political have merged to such a degree that it’s no longer an abstract debate. It’s about our relationships to family. It’s about our anger at what people are feeling that conflicts with what we’re feeling. So it’s not that I’ve ever felt creatively driven to put political ideology in movies, but I’m always creatively driven to put what I’m angry about at the moment into movies.

Do your movies generally have things you’re angry about?

Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

What would be another example of that?

I think there’s that example in all of them. It’s a deceptive term, because that makes it sound like it’s trying to be vindictive or get somebody back by making a point in the movie. And it’s not that. I guess I classify anger in terms of just a primal notion of . . . “Looper,” for example, is very much a father-son story. And it’s rooted in “Fuck you, I’m not going to turn into you.” And there’s something very primal about that. Or “Brick,” rooting it in my experience in high school and the feelings of helplessness and rage and all of that. I don’t think you can make a movie without that as the engine, or I can’t.

But with politics and movies, I can think of movies whose politics I agreed with where I still thought, This is obnoxious or annoying, and why am I sitting through this? Is that something that you worry about?

Oh, my God, there’s nothing worse than tripping into that territory. Yeah, and that’s absolutely terrifying. I think I try to be very conscious of that and work really, really hard to make them, first and foremost, entertainment, and to have all of the stuff layered in there but never lose focus in terms of creating these as rides. But, yeah, that’s terrifying. The notion of getting up your own ass and preaching to people—there’s nothing more obnoxious than that. If I ever do that, please throw a book at me.

Is there a book here?

Oh, no.

You mentioned rage and not wanting to turn into your father. You earlier had mentioned that your dad wanted to be in Hollywood. What’s the connection there?

I don’t know. I had a very good—and also complex, in the way that everyone’s relationship is complex—relationship with my father. It’s not like there’s some sum-upabble, sort of teachable moment from it. The same way that anyone has.

No, you are the only person with daddy issues.

I’m the only white man in his forties with daddy issues, expressed through movies.

How old were you when your father passed away?

It was right before I was offered “Star Wars.”

So he got to see a good chunk of your success?

He did. I gave him a little part in “Looper,” where he got to be shot in the face by Bruce Willis. He was so joyful. I don’t want to make it overly dramatic; it was not like we had some great Shakespearean schism or something, but I feel like we really connected as adults once I started making movies. And, once he could be a part of that, I think that’s kind of where my adult relationship with him was forged.

Was that bittersweet that you had succeeded in this realm that he tried to?

Oh, no, not at all. There was zero of that. No, he was just so overjoyed. He was like a little kid. My first movie memory is him putting me in the car to go see “Star Wars.” So the whole “Star Wars” experience was incredibly tinged by that bittersweetness of “God, can you imagine if Dad was here?” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com