Though the film’s title emphasizes the theme of grief, Giraud and Corteggiani stressed that “The Silent Shore” is not merely a tale of death—it’s, additionally, one of reflection.

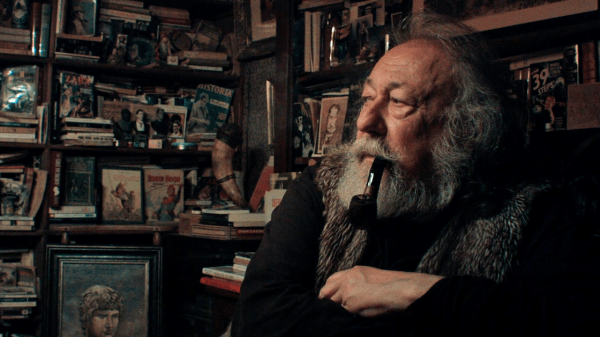

“The Silent Shore,” a documentary by the directors Timothée Corteggiani and Nathalie Giraud, opens with towering trees; a swing, dwarfed by the foliage it hangs from; and, in the midst of all the greenery, tiny, bright garden chairs. Somewhere, unseen birds argue. A thin sheet of mist drapes over everything, so that the moment feels like stepping into a memory, or perhaps a child’s storybook, where the world is still surprising and unknown. The first words of the film are spoken by a voice that’s calm and warm: “We are united in life and death.” The speaker is Aline Dubois, a former social worker who lives in Northern France. Aline has young, playful eyes, clove-colored bangs that cover half her face. She says things like, “I’ve identified a lot with Jane Birkin, even though I can’t sing.” We see Pierre Dubois, too—her husband, an author and illustrator. Pierre has a wild look to him, with lively silver hair that always seems to have just been whipped up by the wind. He wears a big fur vest that makes him look bearish. He writes children’s books about fairies, goblins, and legends, complete with drawings that are at once eerie and whimsical. The pair raised three daughters. Their middle child, Mélanie, died by suicide when she was only seventeen.

Corteggiani and Giraud found “le silencieux rivage,” or “the silent shore,” to be a strong metaphor for mourning or grief. In a video call, they told me that they had just “wanted a title that represented the ‘everything’ of the story.” For two weeks, the pair lived with Aline and Pierre, eating meals with the couple, joking with them, talking, and talking, and talking, beginning recordings in the crisp light of morning and ending when darkness fell. By chance, their filming coincided with the anniversary of Mélanie’s death. In the documentary, on a pale, blank day, they accompany Aline to Mélanie’s grave. We hear Aline say, in voice-over, “That’s our month of May.” We see Aline walking through the cemetery, holding a cane and an umbrella with all the colors of the rainbow. “She died on May 14th. And today’s the day. May 14th.”

The New Yorker Documentary

View the latest or submit your own film.

“We were filming as we were feeling,” Corteggiani said, of the experience of staying with the Dubois and unravelling the story of their lives on camera. The directors decided to shoot on digital, with cinematic lenses and a square, portrait-style frame. For staging, they relied on the house’s abundant natural light. Nature plays a large role in the film—in wide shots of the forest, Pierre and Aline seem small. “We really used [nature] as more than a backdrop—almost like a character,” Corteggiani noted. Pierre and Aline’s back yard is reminiscent of the rich woods he grew up in, in Ardennes, which he calls “a land of hills full of legends.” He talked frequently with the directors about what he refers to as the “ecology of the soul”—humans’ connection with the natural world, the cycles of life, and the fables of our existence.

Though the film’s title emphasizes the theme of grief, Giraud and Corteggiani stressed that “The Silent Shore” is not merely a tale of death; it’s, additionally, one of reflection. They wanted to tell a story of grief, yes, but also of other emotions—joy, melancholy, humor, rage—that live with it. That’s why the directors worked hard to establish who Aline and Pierre are as people before delving into their tragedy and the strange, sometimes mystical occurrences that followed it. “When you know someone, you’re more able to accept the intimacy of what they tell you,” Giraud said. The looks Aline and Pierre give directly to the camera—at times sombre, at times playful or mischievous—add to this intimacy. Giraud and Corteggiani felt that this could help the viewer feel like more than just a viewer. And it does: you feel implicated in a way that’s rare when watching a documentary. The distance one often feels between the camera and the people behind it and in front of it softens a little; the distance between who’s onscreen and who’s watching the screen does, too.

Sourse: newyorker.com