LaTanya Richardson Jackson’s star-studded Broadway revival of August Wilson’s “The Piano Lesson,” is, in a word, magnificent. As an actor, Richardson Jackson has long been part of the countrywide, unofficial Wilson theatre company—she was part of the momentous 2008 Kennedy Center series of staged readings honouring his work and, in 2009, she played Bertha Holly in a Tony-nominated revival of the playwright’s “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone.” The production, now at the Ethel Barrymore, may be Richardson Jackson’s first time directing on Broadway—her 2013 directorial début, “Two Trains Running,” also by Wilson, at Atlanta’s True Colors Theatre Company, is her only other professional directing credit—but her touch here is deft, sure, confident. After all, she has known Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play since its première, in 1987 at Yale Repertory Theatre, when her husband, Samuel L. Jackson, created the character of Boy Willie. There are moments in her thrilling production (which again stars Jackson, this time as Boy Willie’s uncle) when she seems to have known it in some deeper, stranger way even before then.

Hints of the supernatural glimmer in Wilson’s magisterial American Century Cycle (also known as the Pittsburgh Cycle), his epic project to write ten landmark dramas, each addressing a decade of the twentieth century. (He completed the final play, “Radio Golf,” in 2005; he died that October, at sixty.) Nine of the Century plays take place in Wilson’s native Hill District, Pittsburgh’s storied center of Black culture, and, though they each stand alone, a faint, barely heard thread does connect them. That thread might be the blues (“The blues is the best literature Black Americans have,” Wilson once said), or the language, the flights of vernacular poetry that made him as much a bard as a playwright. Yet there’s something else, something . . . backstage of all that as well. In “Fences,” “Joe Turner’s Come and Gone,” and “Gem of the Ocean,” what is seen and what is not seen coexist. Even when we’re immersed in the realism of the world onstage, we can tell that lines of song and old tales about crossroads may be as true as any fact. “The Piano Lesson” brings that awareness of the spiritual to the fore.

It’s not always obvious exactly how many ghosts haunt this particular Hill District house; some are friendly, some are not. Either way, the living occupants greet the apparitions and eerie sounds with only occasional fear. (It is 1936. Seventy-one years after slavery, there are worse things to remember than the dead.) From the moment that the scrim rises on Beowulf Boritt’s set, however, we can see the house is being split by something. Downstairs, in the dark, there’s the usual couch, the usual kitchen, the usual elegant china cabinet, but, upstairs, a ghostly shape flickers in a bedroom (Jeff Sugg did the projection design), and, farther up, there is a roof that seems to have been frozen as it explodes apart—the house is bursting its beams. This non-peace is soon further disturbed: Boy Willie (John David Washington) and his buddy Lymon (Ray Fisher) hammer on the door in the predawn gloom. They’ve driven up to Pittsburgh from Mississippi with a truckload of watermelons to sell, and Boy Willie is eager to rouse his family, to see his sister Berniece (Danielle Brooks), her eleven-year-old daughter Maretha (Nadia Daniel and Jurnee Swan alternate in the role), and his uncle Doaker Charles (Jackson).

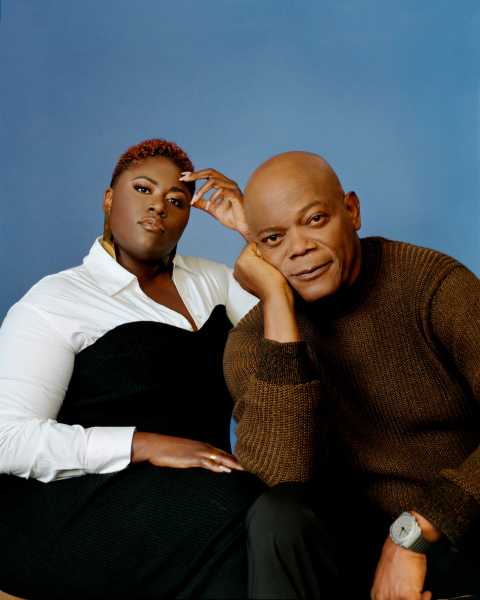

Danielle Brooks stars as Berniece and Samuel L. Jackson portrays Doaker Charles in LaTanya Richardson Jackson’s revival of August Wilson’s enigmatic play.Photograph by Heather Sten for The New Yorker

Brother and sister are at loggerheads over what to do with their most valuable heirloom, a piano carved with portraits of their ancestors. In the face of Boy Willie’s obvious machinations, Berniece is implacable. (Washington’s Boy Willie, impetuous and wide-eyed, often seems to be presenting his arguments directly to the audience, usually because Berniece will not listen.) The instrument is part of the terrible tangled history that links Boy Willie and Berniece to the Sutters, a white family who enslaved their great-grandparents and grandfather. The current generation’s Sutter has just died, and Boy Willie is set on buying the remnants of the plantation, as long as he can get the money. Berniece refuses to sell the piano, though, knowing what it has already cost the family. Also, who killed Sutter? The more that people explain, the less we know. Berniece believes that Boy Willie did it (Lymon, a little confused at the best of times, is her brother’s uncertain alibi). Boy Willie swears it was the Ghosts of the Yellow Dog, Mississippi Furies who wreak vengeance on certain white men. Something is certainly making Sutter’s unquiet spirit walk. First, Berniece says she’s seen him; then it turns out their uncle Doaker has, too.

Everything has two meanings at once: the piano, for instance, represents both the ties of familial love and the still-open wound of slavery. Wilson’s luxuriously digressive scenes take their time, yet they’re also driven by terrific energy—the push-me-pull-you of Berniece and Boy Willie’s quarrel; Berniece’s divided interest in both her almost-fiancé, Avery (Trai Byers), and the wannabe ladies’ man Lymon; the ghostly manifestation’s looming menace. There are more abstract conflicts, as well, expressed by the two wise-rueful, sad-merry uncles, Doaker and Wining Boy (a tremendous Michael Potts). Amid their trash-talking and whiskey drinking, this pair outlines the play’s allegories. Doaker, a railway man, knows a great deal about the impossibility of escape: “What I done learned after twenty-seven years of railroading is this . . . if the train stays on the track . . . it’s going to get where it’s going. It might not be where you going. If it ain’t, then all you got to do is sit and wait cause the train’s coming back to get you.” Wining Boy, on the other hand, is a gambler who has escaped everything, even the things he holds precious, like love and his own musical gift.

Brooks and Washington (Denzel’s son) and Fisher have film and television careers, and this wraps their onstage presences in an attendant glamour, but Samuel L. Jackson—whose Hollywood career is now the stuff of legend—manages to move without any of the pressure of his own cultural weight. When Denzel Washington (also one of the great champions and performers of Wilson’s work) presented Jackson with an honorary Oscar in March of this year, he talked about the “twenty-seven billion dollars” Jackson’s films had earned—“more than any other actor,” he said, shaking his head. Yet Jackson’s particular magic in “The Piano Lesson” lies in how completely he shrouds his own lustre. When the curtain goes up for the second act, Doaker is singing and ironing, and we sit transfixed, not by Jackson-the-institution but by the rasp in his voice. Jackson has grown old with this play; he has been puttering around its haunted edges for more than thirty years.

Despite the many backstories, recountings of dreams, and pauses for songs, the plot must finally wind to a conclusion. I mean, I suppose it does? I’ve seen “The Piano Lesson” several times, and I am always puzzled by the last scene. What exactly is exorcised? What is appeased? The end comes so swiftly after the deliberate, discursive pace of the play that it feels like a door slamming shut. This guillotine sensation is exaggerated in Richardson Jackson’s production because the performances are so exciting that we don’t want them to stop; I could have spent another (close to) three hours watching Jackson’s weary amusement, Potts’s chuckling sadness, the way Brooks makes the whole world seem to recede when her breath catches. There’s also an intoxicating openhandedness about who gets to command the stage. The downtown treasure April Matthis, playing the small role of Grace, pops in, notices that there might be something supernatural going on, and “nopes” right out of the house. “Something ain’t right here,” she says suspiciously, and her hilarious vamoose briefly steals the show. It’s the climactic moment, and Grace gets to stop the action! Only a perfectly balanced, totally frictionless ensemble would allow that to happen.

Balance and measure—“The Piano Lesson” contains these in its smallest and its largest gestures. Even where Wilson himself put his thumb on the scale (his sympathies clearly lie with Boy Willie), the production has, by casting the charismatic Brooks, evened the argument back out. Richardson Jackson’s sense of unhurried calm allows the show to harbor qualities—and enormous performances—that would usually crowd each other. Her staging employs both declamatory presentation and exquisite naturalism, sometimes in the same instant: in one revealing moment, Boy Willie makes a big, aria-like speech while Berniece hot-combs her daughter’s hair in real time, the two women careful to keep the girl’s cheek safe from the heat. I could watch that scene forever. It, more than any line, contains the lesson “The Piano Lesson” teaches, one about family tenderness and dedicated, steady attention. In this tight-knit production, we learn that lesson too from the company itself. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com