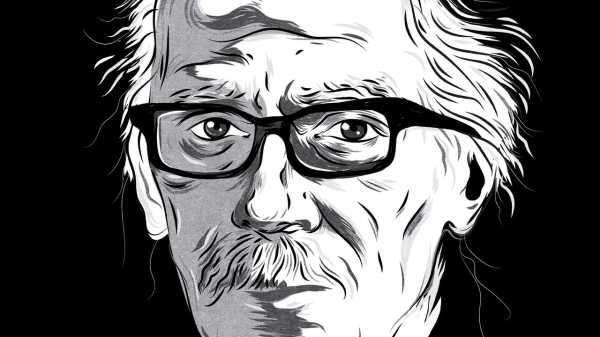

“Sir, please put the phone down I beg you,” Jordan Peele tweeted this past July, at a fan who’d suggested that he might already be the best horror director of all time. “I love your enthusiasm,” Peele added, but “I will just not tolerate any John Carpenter slander!!!” The case for Carpenter as the greatest living American genre filmmaker has certainly been made, whether or not Carpenter himself wants to hear it. His best films, such as his career-making slasher “Halloween” (1978), are breathtakingly composed and suffused with a creeping, matter-of-fact dread that has earned him comparisons to Alfred Hitchcock. Even the more minor titles in his filmography bristle with invention. The novelist Jonathan Lethem once proposed that the centerpiece sequence of Carpenter’s “They Live” (1988)—in which an ornery drifter, played by the W.W.F. star Roddy (Rowdy) Piper, dons a pair of magical sunglasses and perceives a campaign of subliminal subjugation waged by mind-controlling aliens—should be preserved in a time capsule as the apex of neo-B-movie artistry. Yet ever since the dismal critical reception of Carpenter’s sci-fi thriller “The Thing” (1982)—which Vincent Canby derided as “virtually storyless,” “instant junk,” and “the quintessential moron movie”—he has had a chip on his shoulder about the popular opinion of his work. His most famous quote—though it’s hard to confirm if he actually said it—is a comment on his own shifting reputation: “In France, I’m an auteur. In England, I’m a horror-movie director. In Germany, I’m a filmmaker. In the U.S., I’m a bum.”

In conversation, Carpenter, now seventy-four, is terse in a way that might seem hostile if it weren’t accompanied by hints of deadpan comedy. He has an aversion to discussing the art of movies, which might be a by-product of the same tortured perfectionism that contributed to his early retirement more than a decade ago. Carpenter hasn’t directed a movie since his snake-pit thriller “The Ward” (2010), and he’s kept a wary, selective distance from the industry in the time since. I still have an e-mail from a publicist explaining that Carpenter would not be attending that year’s Toronto International Film Festival because he “has been called for jury duty (seriously).” Carpenter composed the music for many of his films, and he agreed to serve as a composer and executive producer for David Gordon Green’s new cycle of “Halloween” sequels, including this fall’s “Halloween Ends.” But bring up this year’s fortieth anniversary of “The Thing”—or the welcome fact that the film today is widely considered a modern classic—and his patience wanes. We spoke twice recently over the phone; Carpenter was in Los Angeles, where he lives with his wife, the producer Sandy King. Both times, he seemed to have an eye on the clock, and was much happier to discuss video games, pro wrestling, and his beloved N.B.A. champions the Golden State Warriors. At times, though, I wondered if he might be enjoying the movie talk more than he let on. Our conversations have been condensed and edited.

I know that you’re an N.B.A. fan and a Golden State Warriors fan. Can we start by talking about that?

Sure. What do you wanna know?

I’m in Toronto. Was this a particularly satisfying title after losing in the finals to Toronto in 2019, and then being out of contention for a while?

They had some disasters in the past few years, starting with K.D.’s [Kevin Durant’s] injury and then, in the same game, it was—

Klay Thompson—he got hurt, too.

It was grim times. It looked like the Warriors might be over. They were underappreciated by the entire league, O.K.? Nobody picked them to be a great team, or even a winning team; they were just ignored. But look what happened: they beat Boston. It was an astonishing win, a wonderful, wonderful win! I mean, I can’t say enough.

Do you read a lot about the N.B.A. or listen to basketball podcasts, or do you just watch the games?

I watch the game. I was a Lakers fan up until, well, up until Lebron came. . . .

Did you ever play any basketball yourself?

I did, but I wasn’t any good. I tried.

Were you a shooter, or did you play inside?

I was a forward. Now, tell me about Toronto. What’s happening there?

You mean the city, or the basketball team?

The city. I made a movie in Toronto a few years ago.

I didn’t want to jump the gun, but you know the movie theatre in “In the Mouth of Madness” (1994)? That’s where I got married, at the Eglinton Theatre.

Oh, my goodness.

What are your memories of Toronto during “In the Mouth of Madness”?

We had some good locations. We had to drive for hours to get to this covered bridge. I remember that—my God. But it worked, you know? Everything we had location-wise, everything we needed was there. It was a good shoot, and then it got cold.

I love the opening of “In the Mouth of Madness,” with all those novels being churned out by printing presses. Was the idea to make something about the way horror comes off an assembly line?

Yes, but the whole thing was . . . I thought that nobody has ever really done a great Lovecraft story. This was my attempt at doing that.

What’s your relationship to Lovecraft?

I’ve been a fan of Lovecraft since I was little, since my dad gave me a book called “Great Tales of Terror and the Supernatural.” I remember first reading Lovecraft then, and just loving him.

Did you have a really visceral imagination as a kid? Was it easy to picture the things in those books in your mind’s eye?

Visceral imagination? I had an imagination. I don’t know how visceral it was, but, yeah, I was a big horror-movie and monster-movie fan, as most of us in that era were. Lovecraft was an author from an era that I really didn’t experience. He’s one of the fathers of science fiction and horror, and I love his stuff, just love it.

One observation that’s been made about your movies is that, like in Lovecraft, evil is something monstrous that characters are forced to confront face to face, instead of it coming from inside them. There are all these moments when the people onscreen simply can’t believe what they’re looking at, or how to deal with it.

I think you’re right. It’s true, and I don’t know where that comes from, exactly. But that’s it.

Were there things that you were specifically afraid of when you were growing up? Any fears or phobias, whether they found their way into your movies or not?

I was afraid of everything when I was little. Everything terrified me.

Did that get better as you got older?

Well, yeah. I mean, I conquered that. My entire life has been about conquering fear and dealing with it, personally and professionally. One of the things I did personally to conquer my fears was I became a helicopter pilot. I got my commercial pilot’s license, and that was just because I thought, Well, if I’m going to make movies about tough guys, I better be one for a minute. It’s a pretty challenging thing to do, fly a helicopter.

Do you remember the first time you managed to get a helicopter into the air?

Sure, of course.

What was it like?

It was fabulous. I mean, they are unlike anything else. They’re dangerous, but, you know, you’re trying to tame the beast. Anyway, I got my pilot’s license in ’82 or ’83—I can’t remember which—and I was off and running.

You didn’t fly any of the helicopters in “The Thing,” did you?

No.

The helicopter sequences in that movie are pretty stunning.

Well, thank you. It was actually a couple different guys flying—one was in Stewart, British Columbia, and the other in Juneau, Alaska, above the ice fields. But, yeah, it’s a helicopter movie.

Those opening images of a helicopter chasing a dog across the ice are so strange and mysterious. Where did it come from?

The animal that we used for the chase was named Jed. He was part wolf, part dog. He was just an incredible animal, so well trained. He actually ran right under the helicopter, because he was so well trained. It’s an unusual scene. Like, what are these guys doing? Why are they after this dog?____

It’s the fortieth anniversary of “The Thing” this year. It’s a movie that’s aged very well after getting a really rough reception.

Maybe so. It wasn’t a fun experience, you know? But I felt about the movie then as I do now: I really love it. I thought I did a pretty good job.

“The Thing” is a remake of the movie “The Thing from Another World,” which was produced by Howard Hawks, and I know you’re a fan of his work. How did you first come to see his movies?

Well, I studied him in film school, and got to see him in person. He came down to talk at the school. I fell in love with his work because he’s so versatile. He did adventures and “The Thing from Another World,” he did cowboy movies, comedies. I mean, he did all sorts of things. I studied the plumbing: how Hawks made movies, how he staged scenes. I was a fan of that. But other than that I loved the strong women he had. I’ve always been attracted to that.

“Halloween” definitely has that with Jamie Lee Curtis, and that character became an archetype for the idea of the “Final Girl.”

Where does that come from, the “Final Girl”?

There’s a book by a film scholar named Carol J. Clover called “Men, Women, and Chain Saws,” where she writes about how a lot of horror films have this character at the end, after everyone else has been killed, who faces down the monster. “Halloween” is Exhibit A.

So that’s where it comes from. O.K.

Can you talk a little more about your time at film school?

Oh, dear, I don’t really talk about that period. I don’t think I made anything very good, and the one thing that came out of film school was “Dark Star.”

Is filmmaking something that you think can be taught institutionally?

The plumbing can be taught. The plumbing is important. You have to learn how to do everything—photography, sound, art direction, writing. You have to know what the rules are, at least, so that you can break them if you want. But can you teach creativity? I don’t think so.

You mentioned Hawks visiting your class. Was there anybody else who you learned from there?

Well, Orson Welles was there. He was pretty good.

Welles would have been in the wilderness a bit at that time.

Well, he was making “The Other Side of the Wind.” He wanted to get some film students to ask questions and he’d film it, so it could go in the movie. We were all guinea pigs in the room because we wanted to talk to Orson Welles. He was a great storyteller and a great guy. He talked about everything—making movies, and also his failures. How did he put it? He said the only movie he took full responsibility for was “Citizen Kane.” The rest were interfered with or changed without his knowledge. That’s the movie he stands behind. One thing he did was downplay the pretension of making movies. Film school was a pretentious time. Everyone was the new artist walking around, and that’s, of course, not true.

John Ford came. He spun a couple tales. He still had his marbles, still had some strength to him. You could see what it was that made him such a great director. We just ate it up.

With Welles and Ford, that’s, like, half of Mt. Rushmore.

It was pretty amazing, I’ve got to admit. Pretty damn amazing.

How much importance do you place on film criticism, or writing about your work?

I find that it’s probably better not to pay too much attention to it. Right? Film criticism changes depending on the times. One minute you’re a genius, and then another minute you’re a bum. Well, both things are not true.

There’s a piece called “American Movie Classic,” by Kent Jones, that quotes you saying the same thing. But Jones calls you a great director, and he makes a really persuasive case.

Well, yeah, I appreciate what he wrote. That’s what people do when they get on a bandwagon. When “Halloween” finally became the critics’ darling, I was “the next Hitchcock”—but only until “The Fog” came out. Then I wasn’t. And, you know, then they start calling you bad names. Many critics don’t like genre films, or at least cheap, low-budget movies. It goes on and on, and it doesn’t have anything to do with the quality of the movies. So after a while I just sort of ignore a lot of it.

Speaking of being called “the next Hitchcock,” did you ever talk about being called that with Brian De Palma, who was also sort of “the next Hitchcock”?

No, we didn’t. . . .

You didn’t know each other?

No.

Were you friendly with any of that nineteen-seventies cohort of American filmmakers? Did you feel like a part of that community, or did you belong to a different community?

What community are you talking about?

The directors who ended up getting mythologized as the New Hollywood: Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Francis Ford Coppola . . .

No, no I don’t know those bums—er, guys. I did know the horror directors. I was friends with all of them: Tobe Hooper and George Romero, those guys.

You’re a big fan of Romero?

Oh, yeah.

Romero’s movies were so scrappy, and that’s true of your earliest movies, which seemed to come out nowhere, such as “Dark Star.”

All those movies felt like we were having to scrap. We didn’t have any money!

It seems like sometimes the most inventive genre movies happen when filmmakers don’t have a lot of resources to work with.

That’s true. That is very true. Now, whether that’s a great thing or not is debatable.

What’s the biggest movie that you ever made, in terms of budget or the scope of the production?

It was probably “Escape from L.A.”

That was a sequel to a big hit, what you’d now call I.P. Was following up a successful movie such as “Escape from New York” anxiety-inducing? Or was it fun to have those kinds of resources to play around with?

It’s better to have resources than not, if you need to get something done. I mean, making movies is all the same. Everything is stressful, low budget or high budget. It doesn’t matter. Everything induces stress and causes aging in a director. It causes a lot of issues—a lot of tsuris, if you will.

Were you good at mitigating that stress on set so that other people didn’t feel it?

I don’t know. I finally had to stop. You know, the stress became overwhelming. But that was me.

Was there a last straw?

It was just a culmination. On “Ghosts of Mars,” I was exhausted. That was the big thing. I remember seeing a behind-the-scenes [featurette], and it showed me on set working, sitting in the scoring session. God, I’d aged. Tired and ancient. And I thought, I can’t do this anymore. It was too rough. For me, it became not worth it. And I didn’t want to say that about movies. Movies are my first love, my life. But, anyway, why am I telling you all this? This is not something I want to talk about.

Is there a particularly joyful moment of moviemaking that you can call up now? Something that was great, that you really felt you pulled off?

I don’t look at things like I pulled something off. I don’t see it that way. I love everything I did. I love all the movies that I made, but I also love stopping and relaxing, too—watching basketball, for instance, or playing video games.

People have tried to make the argument that video games have a relationship to cinema, and a dramatic potential that’s like movies. Definitely video games have become more cinematic in the last few years.

They borrow some of the same things as cinema, but you can’t get away from the interaction that players have with what they’re doing. But video games are young yet. They haven’t really reached their full potential.

Were you an early adopter? Did you play Pong or Super Mario? Or did you come to video games after you retired from directing?

I came to video games in 1992, with Sonic the Hedgehog.

Right on.

That’s where I started, and I fell in love with it. It was beyond me at that point. But my son, who was much younger, he brought me the rest of the way. He introduced me to certain games, like Halo or platform games.

Do you mostly play older games, or do you play new stuff?

I play older stuff, but I play new stuff. I play all stuff.

Is there something you’re playing right now that you’re really enjoying?

I’ve been playing this game for quite a while. It’s called Fallout 76. The Fallout games are fun, it’s like a post-apocalyptic world. This game had a rough launch, with problems and bugs, but I really like it. There’s this incredible game called Horizon Forbidden West. Astonishing game.

Is that like an immersive Western?

Yeah, totally immersive.

Did you ever play Red Dead Redemption?

I did, but I couldn’t get on the damn horse.

That’s not true. Not at all?

Not at all! I gave up. It was too hard.

Sorry, I’m not laughing at you. I’m very bad at video games.

I’m pretty good after all the years I’ve played. But with that one I was terrible. The controls weren’t intuitive, at least for me. But I guess everybody else had a good time. It was a popular game.

I want to ask you something you’ve been asked a million times, and maybe you’ll have a new answer. It’s about working with Kurt Russell. He played Elvis for you in 1979—

He was cast before I was the director. He was sitting there as Elvis, and they couldn’t find anybody who wanted to direct this thing because it looked like a disaster. And, well, I was too stupid, so I said yes.

Did he look or sound like Elvis to you?

Well, he’s an actor. He became Elvis. It wasn’t a question of looking like him. He didn’t look like him particularly. But Kurt is a natural mimic. Perhaps Kurt is the Thing.

I love that.

Well, that’s what I’m here for, to provide fodder for you.

Does Russell imitate you?

He says he can, but I have never seen it.

Do you think that you’re imitable?

I don’t know.

A lot of your titles have a possessive aspect: “John Carpenter’s Vampires,” “John Carpenter’s Ghosts of Mars.” Is that a commercial thing? Is it about pride, or authorship?

I don’t know. It’s just something I wanted to do. I think it has some commercial aspects. I wanted to establish myself as a director quickly when I was young, and that was one way.

There’s a lot of eighties nostalgia now. The font for the title sequence of “Stranger Things” is really similar to the one that you used for a lot of your posters and credits, and, of course, the show takes a lot of things from your movies. Do you think about being a kind of horror brand name? Your Twitter handle is @TheHorrorMaster, but that seems like a bit of a sweet joke.

Look, I’m just a broken-down horror director trying to get along in this world, O.K.? That’s all I’m trying to do, navigate the shoals. I think it’s always fun. A lot of it is a lot of fun.

Is it easier to talk to fans about your movies than to feel like you’re on the record, or speaking for posterity?

Interacting with fans is fun because they’re always so nice. That’s great. Talking about my own movies? God, no. I hate it. I don’t want to do that. They speak for themselves.

It’s nice to think that a movie can speak for itself, but then you have a movie that’s obviously being misunderstood, such as “The Thing.” People didn’t hear what it was saying for itself. You never felt like speaking up on its behalf? Or grabbing people and shaking them and saying, “Don’t you see what this is?”

There was nothing I could do about it. Either they see it or they don’t. It’s too late when it gets to that point.

When you say your movies speak for themselves, do you think that some of them speak more directly than others? “They Live” and “In the Mouth of Madness” seem calibrated more politically or sociologically than some of your other work.

That’s correct. I would say that’s true. But each movie is a story, and each story is different. There’s always a rush to categorize, and I wouldn’t do that.

In “They Live,” I love the idea of casting a pro wrestler, Roddy Piper, as the only guy who can see the world for what it really is—a guy who’s famous for doing things that are fake becomes this voyeur of the real.

You try to find somebody that’s best for the role, right? And I want to caution you about calling wrestling fake. It’s not fake.

No, it’s not. I like wrestling, and you’re right. Go on.

It’s staged, but these guys suffer, especially old-timers. They really suffer bad.

I think that you were at the WrestleManias at Trump Plaza in the eighties, right?

I was.

And, aside from the fact that you were on Donald Trump’s property, were they fun?

Were they fun? Oh, yeah. Always.

Pro wrestling is great narrative and spectacle, or it can be.

When I was younger, they protected the sport more. They didn’t discuss kayfabe or anything like that.

That was the big change in wrestling in the nineties, right? They blurred the lines, and Vince McMahon turned himself into an onscreen character.

There were a lot of reasons for it. You don’t have to go through the licensing by each state, or go through lots of health issues. It’s a way of categorizing it as something else other than a sport.

“They Live” is a movie that’s been appropriated all over the political spectrum.

Right, the neo-Nazis picked it up.

There’s something seductive about thinking that you’re the only person who can see the world for what it really is.

I mean, it’s not a new premise. It’s one that I kind of borrowed from others.

What’s the relationship between composing music and writing and directing?

They’re tasks that are required to complete the film. It starts with a screenplay. It proceeds to directing the movie and then scoring it. My participation in all of these things stems from student filmmaking, when you had zero funds, and you had to do it all yourself. It’s a Jack-of-all-trades thing.

What about composing or playing music outside of film? What’s the plumbing of that?

It’s all based around riff-based rock and roll.

When you were writing the score for “Halloween,” were you thinking about how the score functions in terms of Michael Myers’s role in the film? It’s a bit like the shark in “Jaws”: the music accompanies his presence.

I had nothing like that in mind. You’re just in the wilderness, facing undiscovered territory. It seemed like the right thing to do at the time.

Were there test screenings for “Halloween”?

We didn’t do tests, but I saw it with an audience, sure.

Do you remember how they reacted?

Yeah, I remember.

Some horror directors talk about getting a reaction out of an audience—that if an audience member screams or is frightened, it’s very satisfying. Is there a sadistic impulse in playing with the viewer that way?

Are you accusing me of being a sadist?

No, I think you’re an entertainer, but there can be an intertwining of sadism and entertainment.

I see, I see.

I don’t know what you think of that.

When people enjoy a movie, and they’re into it, and they react to it, I love that. That’s what I love.

And sometimes that pleasure takes the form of anxiety.

That’s the whole idea of suspense, yeah.

Do you feel like there were different kinds of stories that you wanted to tell or didn’t get to tell? Any genres you didn’t get to touch?

You know it! Westerns, dude. Westerns.

“Vampires” is a Western. . . .

Eh, sort of. Hey, how much more time do you need?

Are we O.K. to do another ten minutes?

Sure, sure.

I hope you’re not having a bad time.

I’m having a great time.

So why didn’t you make a Western, then?

It just didn’t ever work out.

The genre was sort of at a low ebb in the seventies and eighties.

That’s it, it died. It used to be a staple of movies, right? Back when I was a little boy, Westerns were everywhere. Then there were adult Westerns, mature Westerns, but they died out.

Is the Western where you get your love of shooting wide-screen?

I think that’s probably true. Not sure where that all develops. I know the movie that influenced me to become a director was “Forbidden Planet,” and that was a CinemaScope film. It was a wide-screen space opera.

You don’t necessarily use wide-screen for big, vast landscapes or scale. You use it for urban environments, and in a lot of very small and intimate settings.

The whole wide-screen thing is just cinematic to me. I love composing in it. I have a difficult time composing in normal vision.

I know that you like to work with cinematographers whose main focus or talent is for lighting instead of worrying about composition.

The best cinematographer I ever worked with was Dean Cundey, a genius with lighting. Everybody is different, so it’s hard to say. Some cinematographers are centered around the entire visual image. Some utilize their profession for ego boosting. Some are there to serve the director, which is what you’re supposed to do. I look at it like composing [music]. My son, my godson, and I are composing the score for the new “Halloween” movies. We’re here to serve the director, not to tell him what to do. We’re there to make his vision, not ours.

Do you ever have to pull back from offering David Gordon Green input on those new “Halloween” movies?

No. I know my job, and I love it.

You’ve been very up-front in the past about sequels and intellectual property, and how you can always go back to material if there’s a chance it’ll make more money. Some people can be precious about it, but you’re very direct. There’s always a sequel to be made. There’s always a remake.

Yeah, sure. If a movie makes enough money, you can be assured that it will.

The rhetoric around “Halloween Ends” is that it’s definitely, finally going to be the last one. Should it be?

I will have to see how much money it makes!

That’s a good answer. Have you had to bite your tongue in the past about sequels or reboots of your movies?

I just don’t say anything. You know, it’s better that way sometimes. I do tend to get in trouble. Every time I open my mouth, I get in trouble.

People would hang on your every word, though. Even if your movies are supposed to speak for themselves, there’s still a lot of interest in hearing what you think.

See, the problem is that I am unable to watch most of my own movies. I become immediately very critical of what I see. I say to myself, “Why did I do that? I know better. Come on.” You know, “I made a mistake there, I was too lazy, too this, too that.” Anyway, I don’t wanna talk to you about that. Those things are feelings I have inside. I’m not going to tell you what I think.

You sometimes seem like you’re on the verge of wanting to talk about things and holding back. Have you ever accidentally let something slip about a new project you’re working on?

Well, I’m always kind of working on stuff. I don’t have anything to announce.

There was a tweet that made the rounds that said you were ending your directorial hiatus, which seemed a bit dubious. I said, “Sure, and F. W. Murnau is about to break his directorial hiatus as well.”

I hear you. I wish I was Murnau.

Do you keep up with new horror movies?

To an extent, sure.

Is there anything you’ve really enjoyed? Because you’ll never get in trouble for saying you enjoyed something.

I thought there was a great one that came along, called “Let the Right One In.” I thought that was a movie that reinvents the vampire genre—it really does—and I admire it for that.

Do younger filmmakers ask you for counsel or to look at their work? Have you found yourself in that mentor role, even if you don’t want to name names?

I used to do that more. I don’t do it quite so much anymore. I mean, it will take my time away from basketball!

This might be a good place to circle back to where we started. With this core, has Golden State got a shot at one more title?

Sure. However, age begins to creep in. Age is unkind to basketball players. They pound their legs and their ankles and their knees.

Have you ever managed to meet any of your beloved Warriors?

I haven’t.

You should throw your name around to try to get to meet them. That’d be a great photo op.

Maybe I will. I mean, it hasn’t worked for me before. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com