When the filmmaker Christine Turner got a call from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) asking whether she’d be willing to make a film about the painters Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, she didn’t hesitate to say yes. She’d followed the work of both artists for several years, once even going to see Sherald’s work in New York while nine months pregnant. And she knew that the only way to showcase Wiley and Sherald in all their glory, she told me, was to “give them the same reverence, dignity, and respect” that they grant their own sitters. The final product, “Paint & Pitchfork,” explores the unfinished legacies of two Black cultural icons, and how in painting themselves, their subjects, and their people into the art-historical record they attempt to rectify the social and cultural absence of, as Wiley says, in the film, “people who happen to look like me.”

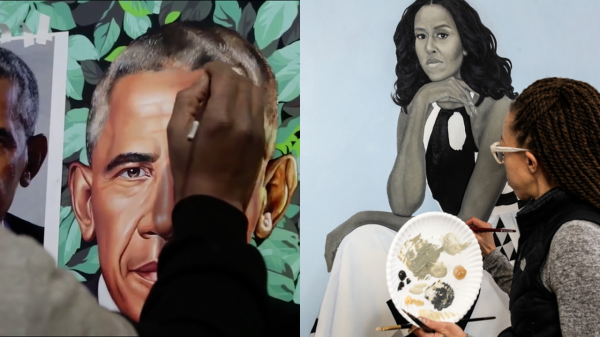

Wiley speaks of his upbringing in South Central Los Angeles as a time when his artistry blossomed and his family ties deepened, even in the face of poverty. In the documentary, photos from those years appear on the screen, accompanied by the instruments that fuel the jazz soundtrack: drum beats introduce a picture of a young Wiley with a Basquiat-esque head of hair; the metal bars of a vibraphone make way for the artist as an adult photographed among a sea of smiling family members, all clad in colorful garments and hugged close. Turner showcases the lush and intricate backgrounds of Wiley’s large-scale paintings before zooming in on the precise details: his palette, his brush strokes, the areas of canvas he meticulously colors in. Wiley explains his intense draw toward seventeenth-, eighteenth-, and nineteenth-century masters such as Diego Velázquez and Francisco Goya, and toward contemporary masters of more figurative art, including Charles White and Kerry James Marshall; partly owing to that mix of influence, Wiley determined that his style was going to be very majestic—and very Black. “I’d look at that,” he says, referring to grand European portraits, “and I’d put myself in it.”

The New Yorker Documentary

View the latest or submit your own film.

The film then pivots to Sherald, who appears in head-to-toe denim, her collar popped and grazing her corkscrew curls. Her roots are in the American South, and she explains how the conservatism of Columbus, Georgia, her home town, became the model of what not to emulate in her life and art. Horns trill throughout a progression of Sherald’s childhood photos, and we see that the striking color schemes of her art are reflected in her clothes—as if that’s when she’d started developing her style. “I did one painting, where I found this young woman that was living outside of the box. I realized that’s the kind of person that I’m looking for,” Sherald says. “These are the people that need to be represented in art history and be on the walls of institutions. These are the people that need to look at something and find their humanity inside of that, because it’s impossible to find it anywhere else sometimes.”

The artists’ time lines converged when they received life-changing commissions from the National Portrait Gallery to immortalize the Obamas. Wiley’s work tends to frame Black men with metaphorical florals and other patterns. In his portrait of Barack Obama, Wiley added botanical representations of the former President’s past, including flowers from Hawaii, Illinois, and Kenya, which reach out from their leafy curtains to embrace the stoic sitter. Sherald’s portrait of Michelle Obama is typical of the artist’s color-blocking style, which emphasizes the stateliness of the former First Lady’s bearing.

Both portraits memorialize their subjects, though no more than the artists aim to do for every other Black person they depict. What unites their work is that it is a direct address to a void of representation—they use their medium to say “yes” to Black humanity when history says “no.” “The question I’ve been asked often is, ‘Will you ever paint anybody other than Black people?’ My answer is ‘No, I won’t,’ ” Sherald says. “I’m here to paint my own ideal and to represent that in the world, and if I can’t do that then something is deeply wrong.” She adds, as the film’s final note, “You should look at a history book and then still see if you want to ask me that question, because the problem is you recognize an absence of yourself, but you don’t recognize the absence of me.”

Sourse: newyorker.com