In the age of electric vehicles, the hybrid is still a contender.

Umair Irfan is a correspondent at Vox writing about climate change, Covid-19, and energy policy. Irfan is also a regular contributor to the radio program Science Friday. Prior to Vox, he was a reporter for ClimateWire at E&E News.

Are electric vehicles hitting a pothole?

Ford announced last month that it was cutting production of its F-150 Lightning electric pickup truck. General Motors and Volkswagen last year said they would reduce electric vehicle manufacturing. All-electric and plug-in hybrid carmakers are struggling too, with layoffs or slowing assembly lines at companies like BYD, Lucid, Polestar, and Fisker. Tesla, the world’s most valuable car company, lost $80 billion in value in January — 12 percent of its market capitalization — after CEO Elon Musk projected lower sales this year.

Meanwhile, EV users are running into some of the harsh realities of living on electrons. Car rental company Hertz last month said that it was selling off 20,000 electric cars — one-third of its electric fleet — and replacing them with gasoline-powered vehicles, blaming low demand and high operating costs. Hertz said the sale resulted in $245 million in net depreciation expenses in the fourth quarter last year.

Drivers around the United States have also run into some unexpected problems. Some EV owners have experienced software glitches, and manufacturers have had to delay deliveries to squash bugs. Public EV charging stations continue to suffer from reliability problems, which recent extreme weather has made impossible to ignore: A sudden Arctic cold blast across the country in January left EV drivers waiting hours at charging stations as the frigid temperatures reduced battery capacities and caused chargers to malfunction.

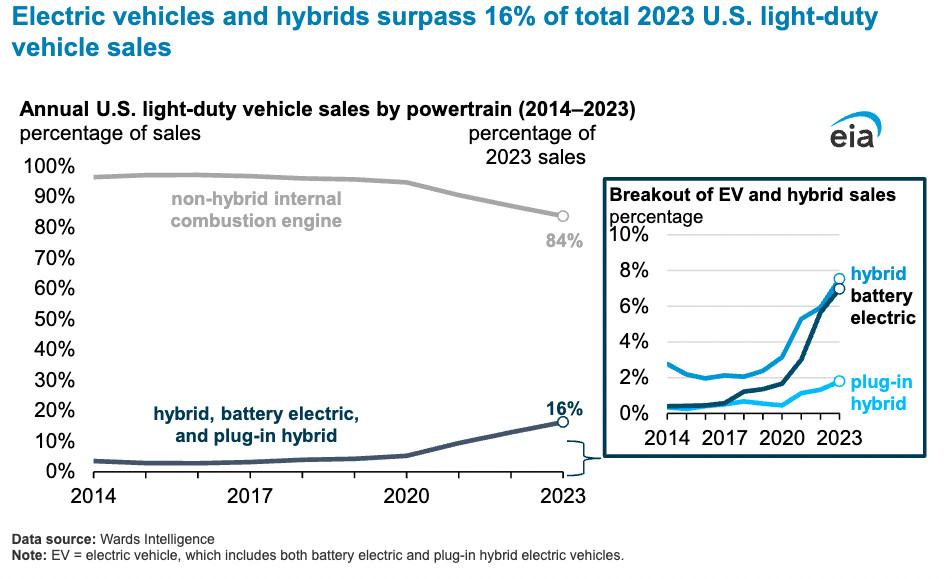

However, the numbers show that electrification is nonetheless charging ahead. Americans bought almost 1.2 million EVs last year — below some forecasts, but still a record high. They now make up 7.6 percent of the US vehicle market.

So Americans aren’t slamming the brakes on electric cars so much as letting up on the gas pedal, and the market could pick up some speed again this year. Ford noted that it’s still expecting growth in EV sales around the world in 2024 and is developing new electric models.

Manufacturers are waging a price war, so new electrics are getting cheaper. While they’re still pricier than their gasoline equivalents, there are lots of used EVs available — many still under warranty. Hertz is currently selling its used Tesla Model 3s for less than $23,000, and you could get one for thousands of dollars less if you qualify for EV tax credits and rebates.

Still, electric cars aren’t on pace for what is ostensibly their ultimate goal: mitigating climate change. Global greenhouse gas emissions reached a record high last year. In the US, transportation is their largest source, accounting for 29 percent of overall emissions. Light-duty vehicles — sedans, crossovers, SUVs, pickup trucks — make up 17 percent of total emissions. The US has committed to cutting its carbon pollution by about 38 percent below current levels by 2030. Nine states now have deadlines for banning sales of new fossil fuel-powered cars.

Last year, the Environmental Protection Agency proposed rules that would effectively require two-thirds of cars sold in the US to produce zero emissions. Electrifying cars is an important step, but many drivers have real and perceived concerns about giving up on gasoline entirely: price, performance, range anxiety, reliability, and charging infrastructure.

So it’s no surprise that hybrid cars — models that blend electric and gasoline power — are more popular than ever, even as some manufacturers have begun pulling them from their lineups. “The number of hybrid model offerings declined in 2023, but sales increased significantly across existing models,” according to the Energy Information Administration.

Americans are buying around as many hybrid cars as fully electric vehicles, and demand is growing.

The appeal of a hybrid is intuitive. But whether hybrids get us to our goals or become a time-wasting detour depends on how technology advances, how policies evolve, and how the market changes.

Electric vehicles did break some promises — and some hearts

EVs hold a lot of promise. A fully electric car operates at 77 percent efficiency, whereas only 12 to 30 percent of the energy from gasoline actually goes toward moving the car, with the rest mostly wasted as heat. Though it’s only as clean as the grid that powers it, an EV charged up by a coal power plant still emits less carbon dioxide on balance than an internal combustion engine. And its lifetime climate impact is smaller, even accounting for manufacturing.

In theory, EVs offer many practical advantages too. Electric drivetrains are usually simpler, with fewer moving parts that can wear out, increasing reliability and reducing maintenance. Driving ranges are increasing all the time, charging times are getting shorter, charging stations are blooming everywhere, and while they tend to be more expensive now, EVs could close the gap with fossil fuel-powered vehicles as they achieve economies of scale.

The real world tells a different story.

Hertz found that EVs in general and Teslas in particular had higher repair costs, about double those of their gasoline counterparts. The company also observed that its customers were more likely to damage Teslas, often because they were using them for ride-sharing services.

Though EVs tend to have robust warranties — typically eight years or more — and fewer components, those parts can be very expensive to replace once out of warranty or when damaged in a collision. A battery pack can cost up to half the price of an electric car, but there aren’t that many mechanics that can fix them, and parts are hard to find.

That means batteries are usually replaced rather than repaired, and insurers often end up totaling EVs that have sustained seemingly minor damage. That raises insurance rates for all EV owners. Meanwhile, some car dealers — which can make as much as half of their profits from repairs and maintenance — are reluctant to stock EVs on their lots.

Chilly weather has proven to be another challenge. While gasoline-powered cars can lose almost a quarter of their range in the winter, the cold can take a 41 percent bite out of an EV’s mileage. Even in warm weather, many EVs aren’t living up to their window stickers. Consumer Reports found that half of the 22 EVs they tested fell short of their range estimates.

Charging infrastructure isn’t where it needs to be either. In frigid conditions, chargers struggle to pump electrons. Many EV owners top up at home, but those who have tried to reenergize on the road have sometimes found chargers to be scarce, inoperable, or slow. Some EV owners have had their cars rendered unusable at public charging stations.

And while manufacturers have been cutting EV prices in recent months, they’re still costly. More than three-quarters of EVs sold last year were classified as luxury vehicles. Many of them were too expensive to qualify for tax breaks and incentives.

In December 2023, 77% of BEV sales were categorized as luxury, according to Wards Intelligence. While the precise definition of “luxury” is debatable, luxury vehicle prices clearly skew to the higher end of the market. pic.twitter.com/avJ0WYDPJD

— Joe DeCarolis (@EIA_One) February 6, 2024

Some of this is just growing pains for an industry trying to find its footing in a rapidly changing market, and many of the technical issues are solvable. However, because of these issues, most EV owners haven’t fully committed to electrification: Roughly 85 percent still have a gasoline-powered vehicle as well. Two-thirds of these households drive the gas-powered car more.

And while many prospective buyers say they’re interested in buying an EV, most change course when the time comes to sign the paperwork. A 2022 survey from Consumer Reports found that 36 percent of Americans were planning or seriously considering buying an electric car, but just 5.7 percent of new cars sold in 2022 and 7.6 percent in 2023 were electric.

The continuing case for hybrids, explained

Hybrid cars and trucks appear to overcome many of the practical challenges that fully electric vehicles currently face. And when it comes to balancing scarce resources, limited public money, and the need to contain climate change, hybrids might be the best way to optimize for all three.

Ashley Nunes, a researcher at Harvard Law School who studies technology and economics, explained that if you’re thinking about climate change, you have to consider what kinds of cars you’re subtracting from the market as much as the cars you’re adding. If an electric car replaces an older, dirtier car, then it’s a gain for the climate.

But if subsidies and incentives encourage someone to buy an EV as a second car when they wouldn’t otherwise, then that could be a loss for the environment. With so many new models of EVs targeted at the luxury market and few in more affordable segments, many drivers may choose to hang on to their gasoline cars for longer.

“Just because an electric vehicle is cleaner than an internal combustion engine-powered vehicle doesn’t mean that it is better to adopt the electric car,” Nunes said. “Is the goal of the policy to buy electric cars, or is the goal of the policy to reduce emissions?”

With that in mind, hybrid cars stand a better chance at replacing conventional carbon-spewing vehicles because their barriers to adoption are much lower than full EVs. Hybrids don’t require chargers and drive like conventional cars. More than two-thirds of cars sold in the US are used, and since hybrids have been on the road for decades, there are plenty of cheap secondhand models for sale.

Hybrid cars come in three main varieties: mild, full, and plug-in. Mild hybrids have a conventional powertrain and an electric drive system but never run fully electric.

A full hybrid (a.k.a. strong hybrid) can run in battery-only mode. Since they still burn some gasoline, one can think of these hybrids as highly efficient gasoline cars rather than EVs, but that’s still an extremely useful trait. Since model year 2004, fuel economy in the US has increased by 6.7 miles per gallon per car on average and carbon dioxide emissions have fallen by 27 percent, according to the EPA’s latest Automotive Trends Report. So until electric vehicles become the dominant form of transportation, increasing fuel efficiency is one of the best ways to reduce carbon dioxide pollution.

Plug-in hybrids might be the best of all worlds. They can function as fully electric for 20 to 40 miles at a time. While that’s a fraction of the range of most full EVs, it’s enough to cover the vast majority of car journeys — almost 80 percent of daily car trips in the US are less than 10 miles, and fewer than 2 percent are more than 50 miles. Plug-ins also qualify for many of the same tax breaks and incentives as EVs.

Another factor to consider is that there’s intense competition for the materials to make lithium batteries, which power most electric cars and trucks but also electric bicycles, scooters, and mobile devices. That’s led to some price increases for battery packs and could start to make EVs less affordable if more cells don’t hit the market.

Hybrid cars could thus yield more carbon reductions per lithium ion cell. Ten plug-in hybrids with a 30-mile range battery could in theory displace more gasoline miles than one 300-mile range EV. Batteries are heavy too, and larger batteries can have diminishing returns on range.

On the other hand, the average car in the US has been on the road for 12.5 years, with many reaching two decades of operation. “It’s not like five years from now we decide EVs are now fine, all those [hybrids] will just disappear off the roads,” said Parth Vaishnav, an assistant professor of sustainable systems at the University of Michigan studying electrification.

So to address climate change and ratchet down emissions as fast as possible, it might still make more sense to invest in full EVs now.

“If you’re optimizing for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, you electrify,” said Samantha Gross, director of the Energy Security and Climate Initiative at the Brookings Institution. Policymakers thus need to do more to bolster supply chains, deploy reliable chargers, and create incentives to make and sell electrics, not just leave it up to the whims of the market. “It’s a systems question, not just a ‘should we build a vehicle or not’ question,” Gross said.

Automakers are taking different routes

While carmakers can build as many EVs and hybrids as they like, it’s still up to customers to buy them. General Motors committed to going all-electric, but the company announced this year that it is bringing back plug-in hybrids.

“Let me be clear: GM remains committed to eliminating tailpipe emissions from our light-duty vehicles by 2035,” said GM CEO Mary Barra during an earnings call last month. “But in the interim, deploying plug-in technology in strategic segments will deliver some of the environmental benefits of EVs as the nation continues to build its charging infrastructure.”

The persistent interest in hybrids has been a validation for Toyota, which has a long history with hybrids but has been more reluctant than other automakers to invest in EVs. In contrast to Tesla, Toyota’s stock price has risen almost 50 percent over the past year.

Joseph Moses, a spokesperson for Toyota, noted that adoption for new drivetrains takes time but can accelerate quickly. It took the company 10 years to sell its first million Prius hybrids and two years to reach its second million.

And while the company is keeping its options open, it has made the leap to cleaner models when it deems the market warrants it, Moses said. Toyota now only offers a hybrid drivetrain for its Sienna minivan and is planning to go hybrid only for its Camry sedan.

Ford is also leaning into hybrids as it cuts back production on some of its EV lines. The company will no longer offer hybrid versions of its Explorer SUV, but it expects to quadruple its hybrid sales over the next five years. The company has seen hybrid sales rise 43 percent over the past year, led by the hybrid Maverick pickup truck, which saw a 118 percent jump.

Those cars will help smooth the shift toward full EVs, though the company hasn’t set a goal for going fully electric. “Research shows that customers that get hybrids are more open to buying an electric vehicle at some point in the future,” said Mike Levine, a spokesperson for Ford.

Where do cars go from here?

Though EVs haven’t begun to nudge greenhouse gas emissions down just yet, they have helped slow the rate of increase, displacing 1.5 million barrels of oil out of 102 million consumed every day, according to BloombergNEF. That displacement is poised to grow to 20 million barrels per day by 2040.

To speed this up, the federal government is offering up to $7,500 in tax credits for new and used EVs, plug-in hybrids, and fuel cell electric vehicles. Many states and local utility companies offer their own additional incentives.

But the US needs vastly more infrastructure to support EVs. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimated that the country would need nearly 27 million charging ports and 182,000 public fast charging stations to support the 33 million plug-in vehicles forecast to be on the road by 2030. That poses immense challenges to the power grid, which isn’t equipped to handle so many vehicles soaking up so much juice in much of the country.

Another issue is that SUVs now outsell cars, undermining some of the forward progress made by increasing fuel efficiency and electrification. SUVs were the second-largest contributor to the increase in global emissions between 2010 and 2018, behind the power sector. Automakers say they are merely responding to what their customers want, but larger, thirstier cars generate higher profit margins, creating an incentive for car companies to sell more of them. Some environmental activists are now calling for regulating or banning ads for gas chuggers.

Again, the goal here is not to increase the number of EVs but to reduce the amount of carbon dioxide emitted from transportation. One of the simplest ways to accomplish this is to reduce driving overall. That comes down to individual decisions but also requires more thoughtful policies around urban planning, more robust public transportation, and safer, easier routes for alternatives like cycling and walking.

So there’s still a long highway ahead for decarbonizing transportation. Costs need to drop further and reliability needs to increase before most drivers will shift EVs from their backup option to their first-choice ride.

Correction, February 14, 1:30 pm ET: A previous version of this story incorrectly described Hertz’s expenses related to its sale of electric vehicles. The company said the sales resulted in $245 million of incremental net depreciation in the fourth quarter of 2023.

Source: vox.com