Winter’s insanely early end, explained in one map.

Buds on the Yoshino Cherry trees surrounding the Tidal Basin are silhouetted against sunrise on March 3, 2024, in Washington, DC. J. David Ake/Getty Images Li Zhou is a politics reporter at Vox, where she covers Congress and elections. Previously, she was a tech policy reporter at Politico and an editorial fellow at the Atlantic.

Whether it’s fewer snow days or disconcertingly hot temperatures, people across the US are experiencing an increasingly common phenomenon: a winter that doesn’t feel wintry.

That’s the result of warmer conditions in many places driven both by climate change and a particularly strong El Nino phenomenon this year. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the 2023-2024 winter is the warmest one it’s seen in the 130 years it’s been tracking. And per the University of Arizona’s National Phenology Network, signs of spring in certain parts of the country — like the budding of the first lilac and honeysuckle leaves — have emerged the earliest they have since the organization began keeping records in 1981.

These developments are part and parcel with the Earth getting hotter overall: per the European Union’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, 2023 was the hottest year on record and the first time the globe surpassed 1.5 degrees Celsius of average planetary warming since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

All this has led to winters getting shorter and appearing decidedly different than they have in years past. As Vox’s Anna North has explained, such changes are jarring emotionally, deeply consequential for the environment, and economically taxing for places that rely on cold-weather activities such as skiing and snowboarding. Shorter, warmer winters are poised to have a host of impacts including throwing off animals’ schedules for hibernation and reducing the size of snowpacks in different places, curbing their water supply.

The factors behind this year’s abridged winter

“As the planet warms up and temperatures increase, the seasonal window for cold weather gets shorter and shorter. That means the onset of what we think of as ‘spring’ … gets earlier and earlier,” University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann tells Vox. Plant-flowering, tree-leafing, and egg-hatching are all markers associated with spring that now happen sooner, Mann notes.

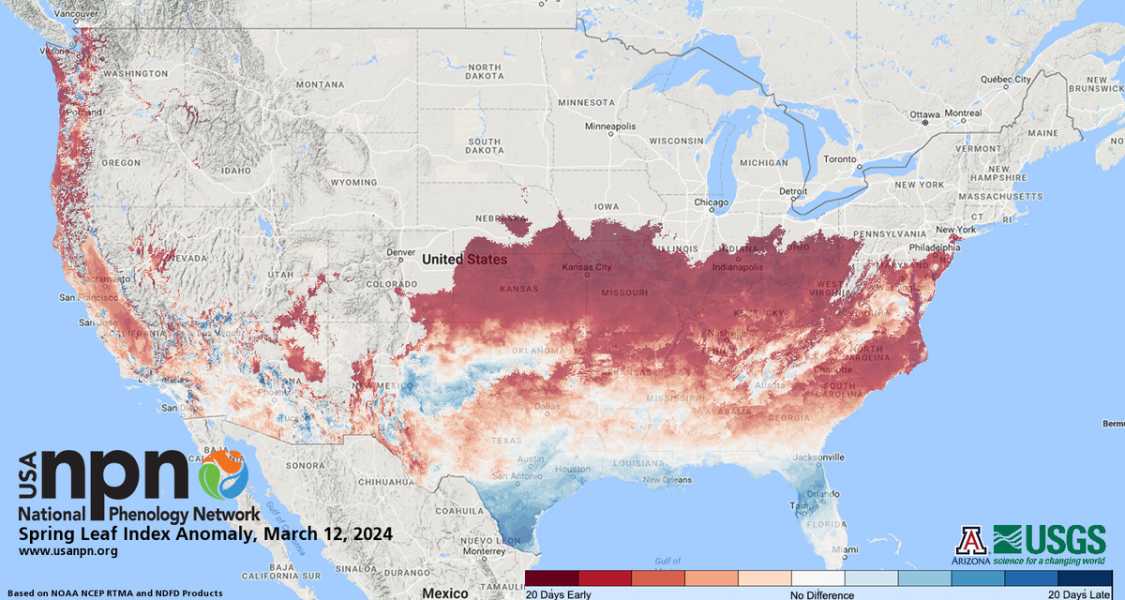

This pattern is evident from a map compiled by the National Phenology Network, which examines when plants are expected to sprout leaves in different parts of the country. That timing is based on a model the network has developed, which uses information about different conditions, like temperature, to project the timing of plant development.

A map from the National Phenology Network maps the places where plants are sprouting leaves earlier, marking them in dark red. National Phenology Network

This year, the organization’s map shows that several states in the Midwest — including Indiana, Illinois, Iowa, and Ohio — are among those expected to see such growth much earlier than usual. As indicated on the map, the places that have darker red pigment are the ones that are poised to experience springtime conditions sooner than they normally do.

“Omaha, Nebraska is 20 days early, Indianapolis, Indiana is 14 days early, and New York City, New York is 10 days early compared to a long-term average of 1991-2020,” the National Phenology Network notes on its website.

As Vox’s Umair Irfan has explained, winter is warming faster than other seasons because colder atmospheres react more strongly to trapped greenhouse gasses. These gases make the Earth warmer, and warmer air can hold more water vapor. As water vapor increases in the atmosphere, it has an even more exaggerated warming impact in cold climates because the air is typically drier during the winter.

Hotter winters have serious consequences

Warmer winters have meant fewer opportunities to revel in the snow, go sledding and skiing, or venture onto the ice. But beyond making certain activities less feasible, warmer winters are also set to have devastating environmental impacts.

Plants and animals could have their growth and hibernation patterns thrown off, for example. According to Theresa Crimmins, director of the National Phenology Network and an associate professor at the University of Arizona, plants’ pollination schedules could become misaligned if they’re emerging sooner than they normally would and the insects that pollinate them aren’t yet ready to do so. Plants that sprout earlier in the year could also have a tougher time surviving if an unexpected cold front or frost comes back and kills off the initial buds.

Pests like mosquitoes could become more prevalent, too, says Crimmins, and potentially contribute to more diseases, since colder winters tend to depress their population.

A shift in winter could have major impacts on water supply as well, leading to a much smaller snowpack than people in the American West and Southwest currently rely on. Frozen snow that slowly melts over time is a major source of water for these parts of the country, and that resource could be severely reduced if there isn’t much snow to work with. During warmer winters, there’s typically less snow and more rain, which leads to smaller snowpacks and potentially huge dips in water as less snowmelt flows into rivers.

“Water supply affects pretty much everything, not just our drinking water: water for agriculture, water for hydropower, water for municipal uses, water for environmental concerns. It’s really comprehensive,” says Cara McCarthy, a program manager at the Natural Resources Conservation Service.

Water from these snowpacks can also help make sure the ground doesn’t become too dry, a factor that contributes to more frequent and more severe wildfires. The National Interagency Fire Center’s forecast through June has projected that parts of the Midwest and Southwest face a higher risk of wildfires this year due to the limited snowfall they received and a higher potential for drought.

Sourse: vox.com