In the 21st century, famine isn’t inevitable. It’s a policy choice.

The war in Gaza is the latest example of the recent rise in global conflict creating humanitarian crises. Abed Zagout/Anadolu via Getty Images Dylan Scott covers health care for Vox. He has reported on health policy for more than 10 years, writing for Governing magazine, Talking Points Memo and STAT before joining Vox in 2017.

This story is part of a group of stories called

Finding the best ways to do good.

Over the long term, humanity has made great progress in eradicating hunger. Famines on the scale of the 20th century’s catastrophes — the Nazi starvation policies, social transformations in China and Soviet Russia that came at the cost of tens of millions of lives — have not been experienced in decades.

There was a general decline in conflict over the second half of the 20th century, with notable exceptions, but in the aftermath of two global wars, more peace has led to less hunger. Agricultural tech advances have led to bigger crop yields, despite the pressures a warming climate has put on food production.

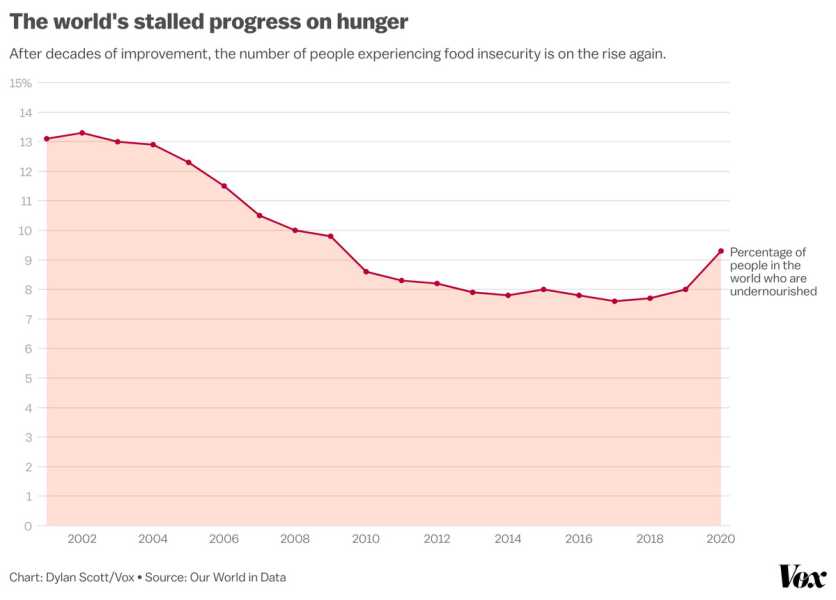

The improvement was such that, in 2015, the UN set the ambitious goal of eliminating world hunger by 2030. Over the last decade, though, all that progress has started to reverse: Instead of moving toward zero, the number of hungry people worldwide has been on the rise.

Conflict is the culprit. Palestinians in Gaza are running dangerously short of food amid the Israeli army’s invasion, putting half a million people — a quarter of the total population — at risk of starvation within the next year. Sudan is experiencing a deadly civil war that has threatened food access, leaving 13 million people facing dangerous levels of food insecurity. The recent Western attacks on the Houthis in Yemen, where some 17 million people are food insecure, have halted humanitarian aid in what is already one of the world’s long-running hunger crises.

For the past decade, almost anywhere there has been conflict in the world, hunger has followed. Gaza and Sudan reflect a longer trend of increasing international and intranational combat: The Syrian civil war and the war in Ukraine have led to serious food insecurity for millions of people. The repressive tactics of authoritarian regimes from Venezuela to North Korea have fostered food crises across the world; in the latter country, an internal crackdown on informal marketplaces and a focus on militarization over the citizenry’s material needs have led to fresh reports of people starving.

“We’re not back to where we were, but the same factors that have historically caused famine, like totalitarianism and using starvation as an instrument of war, they’re now happening again,” said Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University. “That’s why we’re seeing a return of famine.”

Solving hunger is not merely a matter of improving humanity’s technological capacity to produce food — if that were the case, no one today would go to bed hungry. Hunger these days isn’t primarily the result of bad harvests and acts of God, but of politics and policymaking. Conflict and human choices are now the driving forces in global access to food.

For a long time, hunger in war zones was viewed as “a peripheral event rather than a central narrative” in human conflicts, Catriona Murdoch, a senior legal consultant at Global Rights Compliance in London, told me. Now, she said, “what we’re seeing is that it’s not a side issue, it’s not an inevitable consequence [of war] — but actually, in many instances, a deliberate, primary strategy.”

The structural weaknesses of the international system have made it difficult to stop food crises in the midst of war. International criminal law on the use of starvation as a weapon of war is untested, and multilateral groups like the UN have shown a limited willingness or ability to confront states using starvation as a weapon of war.

Until that changes, so long as we have conflict, hunger will follow.

The remarkable progress in alleviating hunger since the 19th century

Human history has for centuries been marred by famines. In 1816, known as the year without summer, a massive volcanic eruption in Indonesia changed global weather patterns, leading to stunted harvests, price increases, and starvation around the world. In the 19th century, Western colonialism often led to mass starvation. Colonial powers exploited local economies for their own gain, exporting crops and other goods while impoverishing the colonized people. When hunger emergencies took root, such as during the Great Famine in India in 1876, colonial governments were often reluctant to intervene aggressively with food aid.

In the 20th century, catastrophic wars and totalitarian governments brought mass starvation. More than 20 million people died from famine between 1911 and 1920. A couple decades later, Nazi Germany adopted an explicit policy of starving the local population during its invasion of the Soviet Union, and more than 4.5 million people died as a result — nearly 20 percent of all Soviet casualties during the war.

In the 1930s, Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin’s Five-Year Plan had already led to millions of people dying of hunger. During Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward in China between 1958 and 1962, another period of forced economic modernization and internal repression, between 18 and 32 million people starved to death as a result of the government’s policies — widely considered the worst famine of all time.

But in the 1980s, global deaths from famine started to drop precipitously. By the 1990s and 2000s, catastrophic hunger was for many years largely isolated to a handful of nations in a near-constant state of conflict (Sudan, Uganda, and Somalia). Since 1980, the annual death toll from famines has been around 75,000 — just 8 percent of the historical average from the 1870s to now, even as the global population nearly doubled.

Economic development across the world and the creation of a professional humanitarian sector post-World War II that delivers food in emergencies and in areas with chronic challenges to food security can be credited in part with that decline. Although extreme weather events still routinely damage harvests — something that is likely to intensify as the climate warms — the world now has a practiced playbook for deploying aid.

By 2015, the UN released a strategic plan with the goal of eliminating hunger by 2030. The following year, when foreign aid averted a potential famine during a severe drought in Ethiopia, scholars openly wondered if the era of great famines was over.

But that goal, always aspirational, has been slipping out of reach.

In theory, we know how to eradicate hunger. Our capacity to produce food has grown exponentially in the past two centuries. Humanitarian groups have more effective means of delivering aid, from cash-based assistance to special food products that deliver vital nutrition in a small package.

But the situation on the ground in conflict zones often makes it impossible in practice.

The sudden omnipresence of hunger crises

Global hunger occurs along a spectrum. Some people may have intermittent problems accessing food, which presents longer-term health risks from undernourishment without the imminent risk of death. Emergency and catastrophic hunger, otherwise known as famine, describe situations in which people have prolonged gaps in their food consumption and experience the resulting malnutrition and mortality.

According to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), a coalition of UN agencies and nonprofit relief groups, a famine is technically underway when 20 percent of households in a region face an extreme lack of food, 30 percent of children have acute malnutrition, and two people out of every 10,000 in an area are dying every day from starvation or hunger-related health problems.

Experts on hunger caution against getting too caught up in the specific terminology. The overarching story is that hunger is on the rise, particularly in war zones like Gaza and Sudan, and there is a real risk of millions of civilians dying in these conflicts because of a lack of food.

Of the 600,000 people worldwide who currently face an immediate threat of starvation, 95 percent of them live in Gaza, according to the IPC. The situation could reach famine levels in the next six months, the coalition warns.

Before the war in Gaza broke out, the territory was already chronically vulnerable to food insecurity because it depended on imports coming through Israeli-controlled crossings for most of its food. Local food production in Gaza, a highly urbanized area built on arid land, has always been limited. Since Hamas’s attacks on October 7, Israel has instituted a blockade of Gaza and restricted the movement of food and other supplies.

Humanitarian groups contend that the Israeli military campaign has made it impossible to effectively deliver food to Gaza. Aid truck inspections conducted by Israel at Gaza’s border with Egypt are laborious and inefficient, while Gaza’s heavily damaged infrastructure makes it difficult to distribute aid once it does get through the border and much of the region remains off-limits to aid workers.

Meanwhile, the recent US and UK airstrikes in Yemen last month have caused humanitarian groups to suspend operations in the country, which was already plagued by some of the highest levels of food insecurity in the world. There are also renewed fears of famine in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, in the wake of yet another outburst of conflict.

In Sudan, a major civil war has reignited one of the world’s long-running humanitarian crises. More than 7 million people have been displaced, while aid groups say their supply trucks have been looted and workers attacked, even as the government makes it difficult to obtain permits for humanitarian workers to move to certain parts of the country. By the end of 2023, 18 million people were in need of urgent food assistance, the highest levels ever seen during what is supposed to be the plentiful harvest season.

Fighting between the Sudanese national government and the anti-government paramilitary Rapid Support Forces is expected to spread to the Gedaref State in the country’s east, a major producer of staple food crops that has so far been unaffected by the war.

“We can’t avoid famine at this point,” said Eric Reeves, an activist and fellow at the Rift Valley Institute who has worked for decades on alleviating hunger in Sudan. “The real question is: How widespread will it be?”

The renewed conflict in Sudan has forced some people to return to the refugee camps in South Sudan, shown here. Luke Dray/Getty Images

In 2021, a group of scholars at the London School of Economics’ Conflict Research Programme identified two key conditions driving contemporary humanitarian crises: war and the presence of transactional politics in which political corruption and repressive violence are commonplace.

Even without the presence of an outright war, authoritarian regimes that adhere to that transactional mode of governance — North Korea, Zimbabwe, and Venezuela being a handful of examples of these “political marketplaces” — tend to have some of the hungriest populations. Their behavior both creates the condition for a humanitarian crisis and makes it more difficult to intervene successfully, by obstructing or commandeering food aid. It is, on a smaller scale, a continuation of the same dynamics that led to starvation under the totalitarian regimes of the 20th century.

Fragile states and paramilitary groups tend to have their own reasons for enabling food insecurity to emerge and persist. Famine is a cheap and effective method of warfare and repression. That ultimately limits their incentives to tolerate humanitarian efforts — and therefore makes it harder to alleviate conflict-driven hunger once it arises.

How the world could fight hunger better

To alleviate conflict-induced hunger, the focus will have to be more on the conflict than on the hunger itself.

Since its founding in 1998, the International Criminal Court (ICC) has named the use of starvation in interstate conflicts as a war crime. In 2019, using starvation in a civil war was added to the ICC’s list of war crimes. (Many countries, however, including the US, have not ratified the Rome Statute, the treaty that created the ICC.)

In recent years, some leading scholars of hunger and famine have pushed to make it politically and morally untenable to use starvation as a tactic of war or repression. But international standards on hunger have been slow to take shape.

That project has made some progress. In 2018, the UN Security Council passed Resolution 2417, in which the members for the first time uniformly condemned the starvation of civilians and the unlawful obstruction of the delivery of humanitarian aid as methods of warfare, and charged the UN’s leadership with carefully monitoring for the emergence of conflict-induced hunger.

“The resolution has not been a game changer, but it has raised the political profile of hunger,” said Michelle Brown, associate director of advocacy at Action Against Hunger.

For these laws and resolutions to have teeth, somebody needs to be willing to enforce them. To date, the UN Secretary-General has not used the authority granted by Resolution 2417 to raise a hunger-related issue before the UN’s Security Council, even amid the international uproar over the risk of famine in Gaza. The world is still waiting for the first successful prosecution of a starvation-related crime.

“You can’t make [starvation] morally toxic without prosecutions,” Murdoch explained. “There needs to be a really clear statement: This type of behavior will be investigated, it will be prosecuted, someone will be held responsible. Otherwise, you’re left languishing in these legal gray zones.”

Starvation is an inherently challenging crime to prosecute. These crimes are often committed in war zones from which it can be difficult to gather thorough, accurate information. A successful prosecution must also prove intent, a challenge in any criminal proceeding, and especially one carried out amid the fog of war. It is easy to imagine a defense centered on the argument that the defendants in question didn’t know that their policies or actions would lead to people starving.

Nevertheless, experts say it is conceivable that some of the hunger crises currently in motion, particularly Ukraine and Gaza, could lead to prosecutions. South Africa’s attempt to bring genocide charges against Israel in the International Court of Justice has put hunger in that crisis front and center. Though that case does not technically turn on the question of starvation, observers told me that a prosecution focused on famine might eventually follow.

“Gaza is the perfect storm, a ready-made prosecution,” Murdoch said. “I hope it happens.”

More consistency from the world’s leading democracies would help set stronger international norms. Human Rights Watch and other humanitarian groups have criticized the US and its allies for picking and choosing when to speak out about abuses.

Despite the passage of Resolution 2417, the UN can still be ineffectual in combating hunger. In some cases, member states are the ones perpetrating policies that lead to starvation against their own population. Any permanent member of the UN Security Council — which includes the US, Russia, and China — can veto an action on the basis of their own geopolitical interests.

“Until the UN is willing to actually address the political decisions made internally by its members, we’re going to continue to have state-induced famine,” Rhoda E. Howard-Hassmann, who leads international human rights studies at Wilfrid Laurier University, told me.

In the short term, more welcoming refugee policies would be another valve for relieving hunger. While refugee camps in foreign countries are hardly an ideal scenario for civilians fleeing war, they are an easier and safer place for humanitarian groups to deliver aid.

In the long run, an international treaty around hunger — similar to longstanding UN conventions regarding torture and women’s rights, which hold more legal weight than a Security Council resolution — could be the most effective way to compel compliance and lay the groundwork for a successful prosecution in a future famine. Some nations, particularly Germany, have also introduced the idea of having universal jurisdiction — meaning the right to prosecute human rights crimes under international law outside their borders. But any such cases will run into thorny questions of sovereignty.

Where there’s war, there’s hunger. As the world enters a new era of increased conflict, the need to sharpen our tools in the fight against hunger is as urgent as ever.

Sourse: vox.com