The justices are threatening to put themselves in charge of every single federal agency. They should resist that temptation.

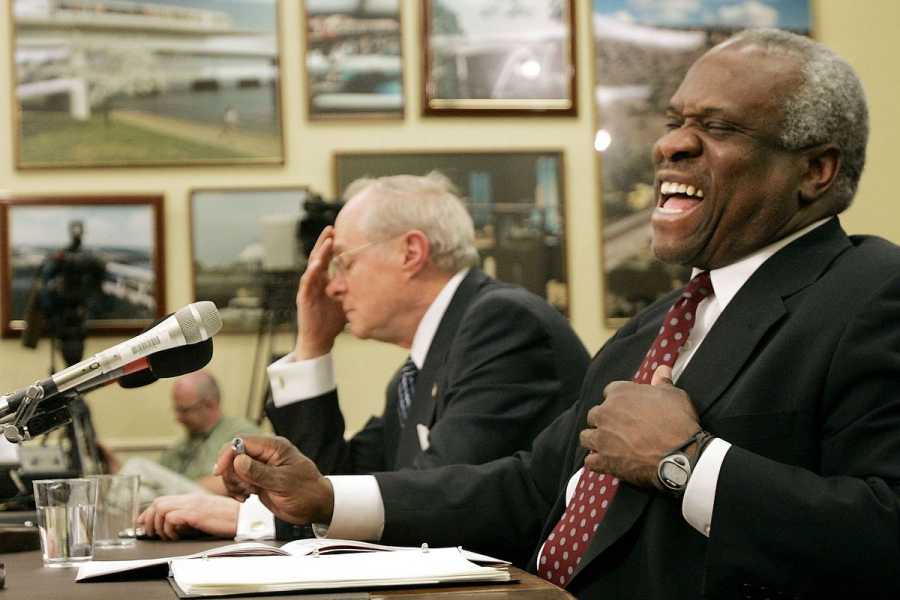

Justice Clarence Thomas (right) laughs. Win McNamee/Getty Images Ian Millhiser is a senior correspondent at Vox, where he focuses on the Supreme Court, the Constitution, and the decline of liberal democracy in the United States. He received a JD from Duke University and is the author of two books on the Supreme Court.

On January 17, the Supreme Court will hear a pair of cases — Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo and Relentless v. Department of Commerce — which ask the justices to seize control of much of federal policymaking. Both cases involve the kind of hyper-technical questions of federal administrative law that ordinarily put nonlawyers (and, indeed, many lawyers) to sleep.

And yet, Loper Bright and Relentless are potentially the most consequential cases the Supreme Court will hear in its current term — including the dispute over whether Donald Trump may remain on the 2024 presidential ballot. The plaintiffs’ argument in these cases is that extraordinarily granular policy decisions, which have historically been made by federal agencies with a considerable amount of expertise on such policy matters, should instead be resolved by a judiciary that lacks any such expertise.

Think of questions like how much nitrogen may be discharged by a wastewater treatment plant in Taunton, Massachusetts, or whether there is “effective competition” between cable TV providers and streaming video providers in Kauai, Hawaii. These are the sorts of wonky, highly specialized questions that lawyers typically do not know how to answer. And lawyers do not become any better at answering these questions if they happen to wear a black robe.

(The specific question in Loper Bright and Relentless is whether the National Marine Fisheries Service may require the commercial fishing industry to pay for some of the costs of placing observers on fishing vessels “for the purpose of collecting data necessary for the conservation and management of the fishery” — not exactly the sort of policy question that is covered in law school.)

Nevertheless, the Court appears to be barreling toward the conclusion that judges, and not federal agencies staffed by experts on topics like wastewater management or the economics of telecommunications, should have the final word on these and countless other difficult policy questions.

Since at least President Barack Obama’s second term in office, the conservative Federalist Society has been on a mission to shift policymaking authority from the executive branch of government to the judiciary. The plaintiffs in Loper Bright and Relentless both raise arguments that would fulfill much of this mission — a mission that conservative lawyers appear to have embraced entirely because it means shifting power away from small-d democratic institutions and toward institutions that are firmly controlled by Republicans.

In the 1980s, when Republican President Ronald Reagan was ascendant, and many federal courts were still dominated by liberal Johnson and Carter appointees, conservative legal luminaries like Justice Antonin Scalia advocated for judicial deference to federal agencies’ policymaking decisions. If you were a Republican, judicial deference to the Reagan administration was clearly in your interest. It meant that important decisions would be made by institutions led by Reagan’s appointees, rather than by judges appointed by Democratic presidents.

By the 2010s, however, this power dynamic had inverted. Republicans had firm control of the Supreme Court, while Obama was in the White House. And so the Federalist Society’s annual lawyers conference became a showcase of proposals to neuter agencies led by Obama’s appointees.

One of the leading proposals, championed by a then-obscure federal judge named Neil Gorsuch, was to overrule the Supreme Court’s Reagan-era decision in Chevron v. National Resources Defense Council (1984), which established that federal judges typically should defer to policy decisions made within the executive branch. Both Loper Bright and Relentless ask the justices to make Gorsuch’s proposal a reality.

The partisan implications of Gorsuch’s proposal should be obvious. While control of the executive branch potentially changes hands every four years, Republican appointees have a supermajority on the Supreme Court and are unlikely to lose control of the judiciary any time soon. Most of the Court’s members, moreover, are close allies of the Federalist Society who were carefully vetted by its leadership. So overruling Chevron means transferring power to one of the GOP’s — and the Federalist Society’s — most durable sources of political power.

But the practical consequences of overruling Chevron are likely to be terrible. Judges simply do not know very much about the kind of policy choices that currently are made by experts within government. So, if the Court declares itself to be the final word on these questions, the United States is likely to wind up a poorly governed nation.

The Court’s GOP-appointed majority, moreover, recently gave itself an unchecked veto power over any federal agency’s decision that involves matters of “vast ‘economic and political significance.’” So the Court already has a (self-given) power to rein in Biden administration actions that it deems to be too aggressive — or too out-of-line with the Republican Party’s policy preferences.

The only question in Loper Bright and Relentless, in other words, is whether the nine justices should have the final word on the many thousands of much smaller policy decisions made by the federal government, which typically go unnoticed by the vast majority of Americans.

If the justices give into temptation, and give the Federalist Society what it’s demanded for the last decade, they are likely to regret it. Chevron does not just protect the public from bad decisions handed down by uninformed judges. It also protects the judiciary itself from an onslaught of lawsuits, often involving highly technical questions that courts are ill-suited to resolve, brought by pretty much anyone who disagrees with one federal regulation or another.

But the Court’s current majority rarely listens to such concerns. And it is particularly unsympathetic to arguments that judges should defer their colleagues within government who know more than they do. So it is likely that, once Loper Bright and Relentless are decided, a simply enormous amount of power will rest in America’s Dunning-Kruger Supreme Court.

Chevron deference, briefly explained

Generally speaking, Congress can regulate in two different ways. One way is simply to pass a law commanding a group of people or an industry to conduct their business in a particular way. If Congress wants to limit pollution, for example, it can pass a law requiring all power plants to use a particular technology that reduces emissions.

But there are several pitfalls to this approach. One is that technology evolves, so a statute that requires power plants to use whatever the cutting-edge anti-pollution technology may be in 2024 is likely to be obsolete in a few years. Indeed, such a law could potentially lock the energy industry into using outdated tech, when the industry would prefer to use technology that is more advanced (and more protective of the environment) than the devices required by federal law.

Few members of Congress, moreover, are likely to know very much about chemistry, engineering, or environmental science. So, if Congress makes the final choice about what devices must be installed in which power plants, it could easily make ill-informed decisions.

So Congress instead passed the Clean Air Act, which requires certain power plants to use “the best system of emission reduction” that currently exists, while also taking into account factors such as cost. Rather than locking the energy industry into a technology that was considered state of the art in the 1970s, the Clean Air Act also tasks the Environmental Protection Agency with determining what the “best system of emission reduction” is at any given moment. And the EPA can issue binding rules, known as “regulations,” which update the requirements imposed on power plants as technology evolves.

This method of lawmaking, where Congress declares a broad federal policy goal, then tasks an agency with coming up with the specifics of implementing that goal at any particular moment, is exceedingly common. One of the primary roles of the 15 federal cabinet departments and various other federal agencies is to make regulatory decisions according to the authority delegated to them by Congress.

When Congress delegates power in this way, there will inevitably be cases where reasonable people can disagree about whether federal law permits a particular agency to take a particular action. Scientists might disagree, for example, on whether a specific new technology does a better job of reducing emissions than the one mandated by an older regulation — and thus qualifies as the “best system of emission reduction” under the Clean Air Act.

Which brings us to the Supreme Court’s decision in Chevron. Chevron held that, when a federal law delegating regulatory power to an agency is ambiguous, courts should defer to the agency’s interpretation of the law. Thus, for example, if scientists disagree on which technology qualifies as the “best system” that can be used to reduce emissions, this disagreement must be resolved by the EPA, and not by a lawsuit. (The Roberts Court, it is worth noting, has already pared back Chevron to limit much of EPA’s authority under the Clean Air Act.)

To understand how Chevron works in practice, consider the facts of Chevron itself. In that case, Congress enacted a law requiring certain power plants to obtain a permit if they built or modified “stationary sources” of air pollution.

During the Carter administration, the EPA determined that this ambiguous term included any ”identifiable piece of process equipment,” which meant that a plant that wanted to modify a single piece of equipment often had to obtain a permit first. After Reagan came into office (and appointed Neil Gorsuch’s mother Anne to lead the EPA), the EPA changed this rule to only require a permit if the entire plant would produce more emissions after individual pieces of equipment were modified.

The key to understanding Chevron is recognizing that both the Carter administration’s more expansive interpretation of this law and the Reagan administration’s more deregulatory interpretation were acceptable. But someone had to decide which construction projects required permits before they could proceed, and a unanimous Supreme Court determined that this decision should rest with the EPA.

Chevron explained that it is better for federal agencies, and not judges, to make these sorts of decisions for two reasons. One is simply that “judges are not experts” in the kind of difficult policy questions that come before federal agencies. So, if we leave these decisions to judges, they will likely do a bad job.

Additionally, placing policymaking authority in the hands of federal agencies makes sense entirely because control of those agencies will shift with the political winds. “While agencies are not directly accountable to the people,” the Court said in Chevron, the leaders of agencies are political appointees, and they answer to a president who is accountable to the voters. And so “it is entirely appropriate for this political branch of the Government to make such policy choices.”

If voters preferred Carter’s environmental policy to Reagan’s, then they were free to elect a new president who would reinstate the Carter policy. But if federal judges, who are political appointees who serve for life, make an ill-considered policy judgment, voters can do very little to rein in those judges.

Chevron, in other words, was at once a good government decision and a pro-democracy decision. It stands for the dual propositions that policy choices should be made by people who know what they are doing, and that those policymakers should be accountable to the American people.

The alternative to Chevron is giving the final say over these sorts of decisions to officials who know very little about most policy questions — and who never can be held accountable to anyone.

The Supreme Court has already given itself a veto power over big, politically contentious decisions by federal agencies

The Court’s Republican majority has already taken one enormous bite out of Chevron. Shortly after President Joe Biden took office, the Court’s six Republican appointees embraced something called the “major questions doctrine,” which effectively allows the Supreme Court to veto federal agency actions that the justices think are too ambitious. (Weaker versions of this major questions doctrine arguably were foreshadowed by a line of Court decisions stretching back to 2000, but the strong version of the doctrine embraced by the current Court did not exist until Biden became president.)

In theory, the major questions doctrine simply requires Congress to precisely define an agency’s power if it wants to give that agency the power to do big things. In the Court’s words, “we expect Congress to speak clearly if it wishes to assign to an agency decisions of vast ‘economic and political significance.’”

In practice, however, the Court’s current majority hasn’t offered much clarity about what qualifies as a matter of “vast economic and political significance.” And the Court’s Republican majority has used this major questions doctrine to veto federal policies even when those policies are unambiguously permitted by an act of Congress.

Consider, for example, the Court’s recent decision in Biden v. Nebraska (2023), which invalidated the Biden administration’s plan to forgive up to $20,000 in student loans for millions of borrowers. The Court did so, moreover, despite a federal law that gave the Secretary of Education sweeping authority to “waive or modify any statutory or regulatory provision applicable to the student financial assistance programs … as the Secretary deems necessary in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency” (such as the Covid-19 pandemic).

Indeed this statute, known as the Heroes Act, did not simply give the education secretary this power, which he was supposed to be able to use as he “deems necessary.” It waived various procedural requirements that federal agencies normally must comply with before announcing a new policy. It explicitly permitted the secretary to dole out student loan relief en masse. And it stated that the secretary may exercise this power “notwithstanding any other provision of law, unless enacted with specific reference to” the Heroes Act.

Simply put, it is hard to imagine a statute that spoke more clearly when it stated that the secretary — and not the Supreme Court — shall have the power to decide who gets student loan relief in the context of a national emergency. But the Supreme Court didn’t care. It held that the student loan forgiveness program violates the major questions doctrine anyway.

The major questions doctrine, moreover, is not mentioned in the Constitution, or in any federal statute. Nor have a majority of the justices ever explained where on Earth this doctrine comes from — although two separate factions within the Court’s Republican majority have offered conflicting justifications for the doctrine. One of these justifications, by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, rests on a parable involving a babysitter and an amusement park.

Yet the major questions doctrine does have one virtue — at least it is contained. By its own terms, the doctrine applies only to questions of vast “economic and political significance.” And, while the Court has shown no compunctions about invoking this doctrine to veto Biden administration programs that spark widespread opposition among Republicans, it has only done so about once or twice every year since Biden became president.

The overwhelming majority of the thousands of policy decisions made by federal agencies are still protected from judicial interference by Chevron, though the plaintiffs in Loper Bright and Relentless hope that will change very soon.

A decision overruling Chevron would effectively bring the same, freewheeling approach to federal policymaking that the Court applies to a few select cases under its major questions doctrine to all lawsuits challenging federal agency actions. Every regulation, no matter how minor, how effective, and how widely accepted by both political parties, would potentially become vulnerable to a lawsuit. And the justices themselves would be overwhelmed with petitions asking them to resolve policy disputes that nine politically appointed lawyers cannot possibly know enough about to think through intelligently.

We can only hope that this Court won’t do something so stupid. The Republican justices have already given themselves the power to veto any policy from a Democratic administration that they deem too ambitious. Why would they also want the massive and ungainly task of micromanaging every single decision made by a regulatory agency, no matter how minor? And how the hell are nine lawyers, whose only staff are a handful of recent law school graduates and maybe a secretary, supposed to perform a task that historically has been carried out by tens of thousands of highly specialized federal employees across many federal agencies?

Sourse: vox.com