The state is using a new untested method that’s prompted backlash.

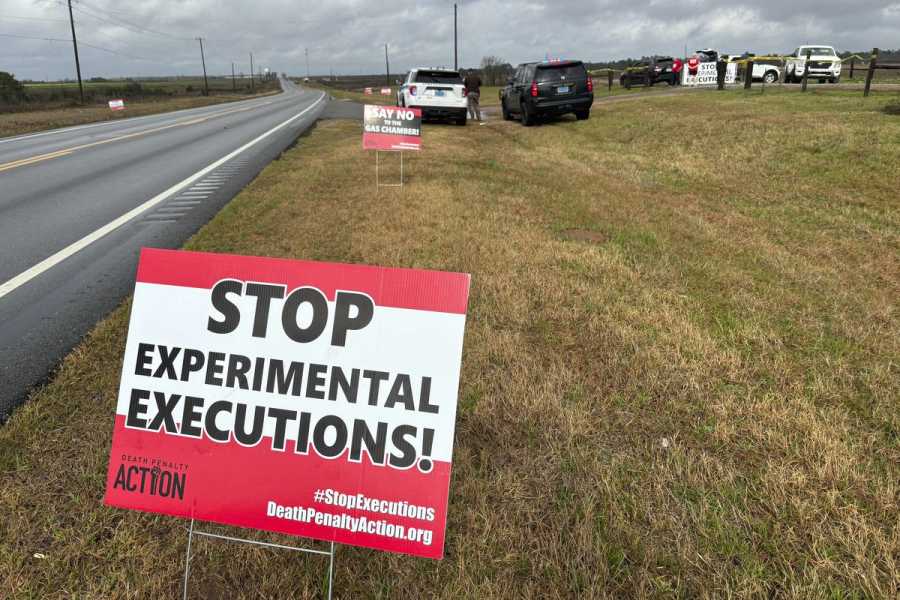

Anti-death penalty activists place signs along the road heading to Holman Correctional Facility in Atmore, Alabama, ahead of the scheduled execution of Kenneth Eugene Smith, on January 25, 2024. Kim Chandler/AP Li Zhou is a politics reporter at Vox, where she covers Congress and elections. Previously, she was a tech policy reporter at Politico and an editorial fellow at the Atlantic.

A controversial Alabama execution taking place on Thursday has reignited scrutiny of the death penalty and highlighted the enduring nature of the practice despite attempts to end it.

Physicians and human rights experts have condemned the execution — which relies on an untested method known as nitrogen hypoxia — because there are concerns it could be painful and inhumane. Alabama is planning to use this method on an inmate named Kenneth Smith, after the state botched his first scheduled execution in 2022 when it couldn’t find an accessible vein for a lethal injection. Smith was sentenced to the death penalty after he was convicted of capital murder in 1988.

Using nitrogen hypoxia, the state will place a mask over Smith’s head that contains nitrogen instead of oxygen, an action that will eventually suffocate him.

Though a slim majority of Americans still back executions — Gallup’s November 2023 polling found a new low of 53 percent to be in favor of executing convicted murders — support has been declining for three decades, since a peak in 1994. Medical and ethical questions have also led critics to call for the abolition of the death penalty. And Gallup found that, for the first time, more people now feel the death penalty is unfairly applied than those who believe it’s fairly applied.

These stances have gained steam in recent years, with some pharmaceutical companies refusing to supply lethal drugs and equipment to conduct executions. Corporations like Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson are among those that block the sale of drugs and medical supplies for this purpose. Politically, the idea has begun to take hold as well. As part of his presidential policy platform in 2020, President Joe Biden said he’d work to abolish the federal death penalty, a proposal he’s been scrutinized for failing to follow through on. More than 20 states have also abolished the death penalty.

States like Texas, Florida, and Alabama have held out against this pressure, arguing that the death penalty is a fitting punishment and deterrent against violent crime. These states’ insistence on using the death penalty in an environment where there are fewer avenues for killing people has also led them to embrace more extreme measures, like firing squads and nitrogen hypoxia.

Alabama’s decision to pursue an untested method only adds to longstanding concerns that have been raised about the death penalty, while underscoring how committed some states are to keeping it.

The ongoing fight over the death penalty, briefly explained

Critiques regarding the use of capital punishment have increased in the last decade as opponents have emphasized the racial disparities in its application, identified worries about how humane it is, and cited cases when innocent people have been convicted. Among the chief problems that have been raised are that people of color are much more likely to be sentenced to executions than white defendants and evidence that it does little to deter violent crime.

Ethical concerns are also a major part of the equation. Smith’s attorneys have argued, for instance, that the state may not be able to conduct his execution without concerning side effects that draw out the killing. There are also worries that Smith could choke during the process if he vomits while it’s taking place. And as UN human rights officials have warned, nitrogen hypoxia could “amount to torture or other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment.”

Lawyers for the state of Alabama, meanwhile, have defended the practice and said that it will be painless, that Smith will be unconscious within seconds. Similar methods have also been used in assisted suicides in Europe. In recent weeks, Smith’s counsel put in a last-ditch plea to block the execution on the grounds that it violates his constitutional protections against “cruel and unusual punishment,” but the Supreme Court declined to do so.

“I think the various practical problems of the death penalty have generated a public opinion movement against it,” says Frank Baumgartner, a political science professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill who has specialized in the study of capital punishment. “It started with innocence but has spread to botched executions, cost overruns, time delays, [and] lack of deterrence value.”

Democrats, in particular, have embraced efforts to roll back or get rid of the death penalty entirely. In the Gallup survey, just 32 percent of Democrats said the death penalty should be applied to someone who committed murder while 81 percent of Republicans said the same.

Actions by Republican-led states, like Alabama, have underscored the contrast between the two parties. Those who favor the continued application of capital punishment argue that it deters violent crimes, that it’s fitting retribution for crimes like murder, and that it brings justice to the families of victims. The case for the death penalty is also often made in conjunction with other “law and order” rhetoric during times when violent crime rates are high.

The use of the death penalty overall, however, has been on the decline. Although 27 states still allow the death penalty, 14 of those have not conducted any executions in the past 10 years, according to CNN. Executions have dwindled since 1999, which marked a recent high when nearly 100 people were killed. In 2023, 24 people were executed across five states.

These declines are due to political backlash toward capital punishment, changes in the law that have raised the legal bar for such sentences, declines in crime in recent decades, and better representation for capital defendants.

“I think anytime a state engages in a highly controversial act concerning the death penalty, it adds one more pebble on top of a pebble mountain of opposition,” says Deborah Denno, a Fordham University law professor who has specialized in the study of capital punishment. “That said, the death penalty is deeply rooted in the US — it’s part of our identity — and it’s going to take a massive number of pebbles to change that fact.”

Sourse: vox.com