Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

I believe that sometimes, when we look at works of art, we long to recapture lost moments of the past – a golden age when we experienced a profound and unforgettable emotion from looking at a painting, photograph, or drawing, when its beauty and power made us feel part of the world, less isolated. As a child, I spent a lot of time looking at the black-and-white photographs in Vogue photographer Irving Penn’s second book, Worlds in a Small Room. First published in 1974, the book reflects Penn’s fascination with the importance and intimacy of space. Setting up temporary studios in places like Morocco, San Francisco, and New Guinea, he focused his patient, detailed eye on how we present ourselves. I remember being captivated by images of Peruvian children leaning against a stool in floppy hats, and one of three young women from Dahomey, dressed in beautifully knotted headdresses and minimal jewelry. What attracted me to the book—though I couldn’t articulate it then—was that Penn’s photographs weren’t limited to the notion of “difference.” He was interested in his subjects because they were fascinating, as compelling as the white hippie family he met in California in the late Sixties and the beauties who had posed for Vogue for decades. It seemed to me that Worlds in a Small Room had nothing to do with “universality,” the ethic that Edward Steichen had tried to articulate in his controversial 1955 Museum of Modern Art exhibition, The Family of Man; rather, the book was about the excitement of specificity, about the way the clothes and jewelry of Penn’s subjects spoke not only of their backgrounds but also of how they wanted to be seen.

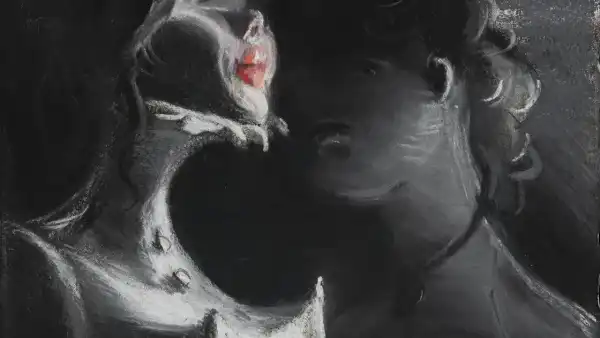

“Cold”, 2025. Work by Sani Kantarovsky / Michael Werner Gallery

Much of the art that has attracted attention in recent years has looked outward, critiquing a world that does not conform to the artist’s expectations. And while I learned a lot from these works, I also missed what Virginia Woolf described in her novel Jacob’s Room as the “spiritual suppleness” of an intimacy in which “mind is indelibly impressed upon mind.” This is what I saw in Penn’s photographs, and what I have noticed in recent months in a series of exhibitions where artists seem to be exploring the small worlds hidden in rooms. It all began in late spring with Sanya Kantarovsky’s Scarecrow (now closed) at the Michael Werner Gallery. Kantarovsky, born in Moscow in 1982, immigrated to the United States at the age of ten. I knew very little about him when I went to the exhibition, and at first I didn’t know how to respond to the emotions his work evoked, since it opened a door to a vulnerability I had unknowingly locked away. The first work I noticed was a small painting of spiders that reminded me too much of Louise Bourgeois’s terrifying and banal constructions; I couldn’t see the point of it, other than that it was a beautiful exercise in color. But then I came to the large-scale canvas Cold (2025) and realized that by depicting these arachnids using their web houses to catch live food, Kantarovsky was expressing something about our own ways of luring people into our personal space and then perhaps betraying them. Cold, measuring 180 by 140 cm, shows a long-legged, salmon-colored naked man lying on a bed, with

Sourse: newyorker.com