Amazon still hasn’t officially announced where its HQ2 will be located, but reports suggest that the company has chosen to split its second headquarters between two cities: New York City and the DC suburb of Arlington, Virginia. This should, at least in theory, be cause for celebration for these cities. Amazon framed the hunt for its HQ2 site as a national competition from which the winning city would receive tens of thousands of new jobs.

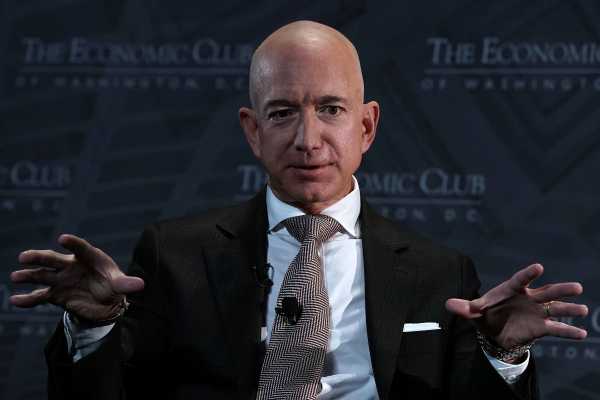

“We expect HQ2 to be a full equal to our Seattle headquarters,” Amazon founder Jeff Bezos said in a statement announcing the HQ2 hunt last September. “Amazon HQ2 will bring billions of dollars in upfront and ongoing investments, and tens of thousands of high-paying jobs. We’re excited to find a second home.”

But as the news leaked that New York and Virginia were the chosen sites, locals and community groups in both cities seemed geared up to protest, not celebrate.

“It is absolutely disgusting what we’ve seen reported in the New York Times: that [Andrew] Gov. Cuomo is offering them likely in the range of hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars,” Deborah Axt, the co-executive director of the activist group Make the Road New York, told me. That money, she said, is “desperately” needed to fund “schools, affordable housing, and to tackle the homelessness crisis. Instead, that money is being offered to the richest man in the world.”

If Bezos is to be believed, Amazon’s presence would be an indisputable benefit to the chosen cities — but activists aren’t buying it. The road to HQ2 has been a bumpy one, and the subsidies cities have offered Amazon, as well as the company’s history in Seattle, may explain why community groups view Amazon HQ2 like a threat, not a victory.

For months, experts have been warning that being the home of Amazon’s second headquarters would be a bad deal for the “winning” city, which would likely strain under an influx of upwardly mobile tech workers. The anti-HQ2 narrative took hold just weeks after Amazon put out a request for proposals last fall and is spurred not only by fears that regular people will be forced to subsidize the tech giant’s expansion, but also by a general distrust of big companies in general and Amazon in particular.

NYC and DC activists have opposed HQ2 for months

Last October, about a month after Amazon announced the HQ2 competition, a coalition of New York City-based community groups wrote a letter to Mayor Bill de Blasio, asking him not to offer tax subsidies or other financial incentives to the company.

“You should focus on pushing Amazon to be a better corporate citizen and improving how it treats communities and workers,” the letter read. “You should also ensure that this multibillion-dollar company, [which] already has a significant presence in New York, does not receive financial incentives simply for doing business here. New York communities are facing massive cuts to public goods and services, and working families are trying to make ends meet.”

The de Blasio administration claims not to have offered Amazon any special subsidies or incentives, but Gov. Cuomo did offer the company a still-undisclosed benefits package. Last week, Cuomo joked that he’d rename Newtown Creek — a heavily polluted Superfund site — the “Amazon River” if the company chose to place HQ2 in New York City. “I’m doing everything I can,” he told reporters this week. “I’ll change my name to Amazon Cuomo if that’s what it takes.”

Act of Make the Road New York, which signed the letter to de Blasio, told me that Amazon’s presence in Long Island City — the Queens neighborhood Amazon is reportedly eyeing for its New York HQ2 office — could be disastrous. “That’s one of the epicenters of gentrification in the city,” she said.

The as-yet-undisclosed tax subsidies being offered to Amazon would starve the city of necessary resources, Axt said. “What we are seeing here is a potential massive giveaway of taxpayer dollars for the benefit of the richest man in the world and New York State real estate developers,” she said. “We do not need to be lining the pockets of the real estate moguls who control this state’s politics.” After the Wall Street Journal reported late Monday night that Amazon would likely announce its picks on Tuesday, Make the Road, state Sen. Michael Gianaris, city council member Jimmy Van Bramer, and other community organizations announced a “no to Amazon HQ2 in Long Island City” protest.

In March, activists from the DC area petitioned the District’s mayor, Muriel Bowser, to “address the social, racial, and economic inequalities that plague our region” instead of trying to lure Amazon. “In a city with a housing and homelessness crisis, where tens of thousands of longtime black residents have been pushed out over the last decade, our city leaders are clamoring to bring in up to 50,000 new, likely affluent residents, without any conversation about the impact on longtime residents,” the activists’ anti-HQ2 website, called Obviously Not DC, read. “And they’re boasting about 50,000 jobs, a made-up number invented by Amazon to spark a bidding war.”

If the reports about HQ2 being split between two cities are correct, that means that neither city will benefit from the addition of 50,000 new jobs. It’s possible that Amazon could choose to split its investment in half — theoretically, 25,000 jobs and $2.5 billion per city — or unevenly between the cities. It’s also unclear what kind of deal Amazon reached with each city, and whether the 50,000 jobs figure was ever a guarantee to begin with.

In May, more than 100 activists from a dozen-plus community organizations called on the governments of Maryland, Virginia, and DC to be transparent about what they offered the company and urged them not to offer Amazon any financial incentives. Erin Shields, an activist who organized the meeting, told the Washington Post that the DC area wasn’t ready for a company like Amazon to move in.

Stephanie Sneed, the co-director of the DC-based Fair Budget Coalition, similarly said that local governments shouldn’t be offering Amazon subsidies when they haven’t adequately funded services for homeless people, immigrants, and domestic violence survivors, particularly given the dearth of affordable housing in the DC area. “This is not about Amazon,” Sneed told the Post, “but about the future of this city.”

The Amazon effect: high rents, congested transit

The fear that Amazon would exacerbate gentrification in the New York and DC areas — both of which are suffering from homelessness crises and a lack of affordable housing — is not unfounded.

A Zillow analysis found that rents in Seattle, home to Amazon’s main headquarters and more than 45,000 of its employees, increased by 31 percent between 2013 and 2018, and home values increased by nearly 73 percent during that same time frame. Rising housing costs have led to the displacement of low-income families in the Seattle area and has contributed to the city’s ongoing homelessness crisis.

That degree of growth — and the rise in inequality that followed — wouldn’t have been possible without Amazon. Instead of helping alleviate the problems its presence in Seattle has created, Amazon helped kill a tax on businesses that would have funded affordable housing and, presumably, mitigated some of the effects of the city’s ongoing housing and homelessness crises.

It’s likely that Amazon placing such large offices in both New York and Arlington would have similar effects in those cities. New York’s subway system can hardly handle the strain of the city’s existing population. DC’s traffic problem is so bad that it recently ranked as the sixth most congested city in the US.

And both New York and the DC area are struggling to build affordable housing. Nearly half of all renters in DC’s “inner region,” which includes Arlington, are cost-burdened, meaning they pay more than one-third of their income in rent, according to the Urban Institute. In New York City, more than half of all households were rent-burdened in 2016, according to a report by the Furman Center for Real Estate and Urban Policy at New York University.

Grant Long, a senior economist at the real estate listings website StreetEasy, told me that an Amazon presence in Queens could lead to higher rents, not only in Long Island City but in neighboring areas as well.

“Amazon’s reported selection of Long Island City for part of its expansion is likely to set off a new wave of housing speculation in Queens, where sales prices have already risen 5 percent over last year,” Long said in an emailed statement, though he added that Amazon splitting its headquarters between two cities would could also reduce the impacts its presence has on any one city:

Skylar Olsen, Zillow’s director of economic research and outreach, similarly noted that large, prosperous cities like New York and Arlington may be more prepared to absorb the population growth. “It’s going to be a big influx of people no matter where you are or how big the city is,” Olsen said, “but the bigger the city is, the better they’ll be able to respond, because it’s a smaller hit to their overall population.”

Even if New York and Arlington are more prepared to handle Amazon than smaller cities, critics worry that Amazon’s presence in these cities will adversely affect their most vulnerable residents.

“We don’t know, in the case of either Arlington or New York — because their bids are secret — what’s on the table,” Stacy Mitchell, the co-director of the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, told me. “But these cities are apparently offering to pay Amazon to show up instead of the other way around. Amazon was very clear, when it talked about where it wants to be located, that it wants places with good transit and all these other amenities. Those things cost money. If you want to reap the benefits of that, you have to pay for it; instead, they’re asking for a subsidy.”

The HQ2 selection process was flawed from the start

More troublingly, it’s becoming increasingly clear that the struggling small and midsize cities that tried to woo Amazon — like Gary, Indiana, where one in three residents live in poverty — were never really in the running to begin with.

Some critics of the HQ2 selection process say that Amazon always knew where it wanted to place its new office — or offices — but faked a national competition in order to wrangle as many incentives as possible from those cities. “Like all corporate site election, the HQ2 process is a rigged game, where the company knows the answer in advance and sets up a fictitious competition to wrest maximum incentives,” CityLab’s Richard Florida wrote in May.

The very cities that would have benefited from HQ2 were never going to be chosen, critics like Florida and Mitchell say. And, Mitchell adds, these cities’ ongoing financial problems — and, conversely, the relative prosperity in large cities like New York, Seattle, and Arlington, particularly among high-income workers — are also the result of Amazon’s business model.

“We’ve been seeing growing concentration across the economy, and Amazon is an essential figure in that. One of the consequences of economic concentration is that it’s mirrored in an increasing disparity, a growing divide in our geography,” she said. “There are these large swaths of the country that have seen nothing in [the post-2008 recovery]. They’ve seen no net new business growth. The jobs they’re getting are low-wage jobs. Amazon is part of why that’s happening, because they’re killing off all these competing businesses, whether it’s main street retailers or small and midsize manufacturers that can no longer make it. When you reduce the entire consumer goods economy to a single pipeline, that means that all kinds of other companies are going to fall by the wayside. Now you have cities and towns that lack businesses, that lack the headquarters they used to have.”

For Mitchell, tax breaks and other incentives weren’t the most valuable gift cities offered Amazon. “Amazon now has very fine-grained data and information and, in some cases, future intelligence about [the 238 cities that submitted HQ2 proposals],” she said. “They’re going to use this data to site all kinds of things: stores, warehouses, offices, tech centers. It seems to me that this is the most valuable thing Amazon has gotten out of this, even accounting for the billions of dollars in subsidies that they are likely to walk away with.”

She added that the creation of these proposals required a lot of time and effort, particularly for smaller cities. “They certainly spent hours on it; they certainly spent staff time on these proposals,” she said. “There are a lot of communities that are struggling with cutbacks, so that time is very precious.”

Amazon tricked these cities into thinking that by offering millions of dollars in tax breaks and other incentives, they could be chosen as the site for the company’s second headquarters — and, as a result, finally experience the economic resurgence they missed out on in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. Instead, these cities’ governments spent countless dollars and hours on proposals that never made a difference. But there’s always a chance that they’ll be chosen as the site for a new Amazon warehouse or distribution center instead.

Sourse: vox.com