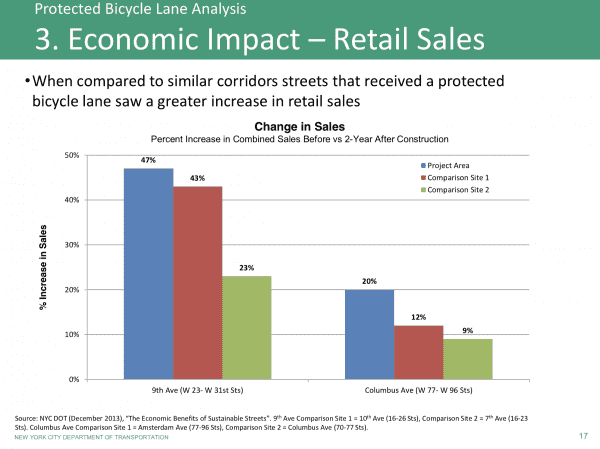

The pilot was, by many accounts, a roaring success. While bicycle volumes increased 65 percent on the corridor, crashes with injuries decreased 48 percent. For businesses that operated along the protected bike lane corridor retail sales increased, outperforming control sites. And the parking-protected design assuaged concerns over vehicular access that often fuels anti-bike lane sentiment.

The 9th Avenue pilot was the catalyst for a transformative era of urban design in New York City. Today, the city boasts roughly 1,200 miles of bike lane, with 120 miles protected. You can watch the video above for a full explanation on why protected bike lanes help promote cycling and safer streets for everyone.

I spoke with Sadik-Khan, who now leads the urban transportation group NACTO, about her career as an urban planner and about weighing the costs and benefits of protected bike lanes. Below is a transcript of the conversation, which has been edited for clarity.

Carlos Waters

What was your job in 2007?

Janette Sadik-Khan

Well, in 2007 I had just been appointed transportation commissioner by Mayor Michael Bloomberg. And I was appointed right on the cusp of the release of this plan called PlaNYC, It looked at how (the city) was going to accommodate the million more people that are expected to move to the city by 2030 and still improve the quality of life in neighborhoods and business districts. And that had really profound implications for business districts and how we managed our streets.

Because we weren’t going to accommodate a million more people by double decking our streets and highways. We needed to accommodate this growth by making it easier to walk around, to bike around, to bus, and make it safe for people that were doing so. That was the really big moment, and one of the really big first tasks I had was to basically triple the number of bike lanes on the streets of New York City.

Carlos Waters

Could you let me know what cycling was like in New York City in the 2000s? Was it a nice place to cycle?

Janette Sadik-Khan

If you were a cyclist in New York City, in the 2000s it was almost like you were a cast member from Escape from New York. It was not a friendly place. Maybe if you were an extreme sports person, it might work for you. Because you were dodging cars, no dedicated lanes, it was dangerous. It was not a place to have any kind of safe commuting regular transport experience.

Our streets had not changed, really in 60 years. And when you think about it, so many of the things in cities change over 60 years. The businesses change. The technology has changed. The people have changed. All things have changed. But in city after city — and New York was no stranger to this — all of the concrete and steel was exactly the same. It hadn’t changed.

And when you think about it, that’s crazy. I mean, if you didn’t change the way you did business, your major capital asset, you wouldn’t still be in business. And that was absolutely the same in transportation.

Carlos Waters

How does it feel to look at New York City’s streets now as opposed to then?

Janette Sadik-Khan

It’s really exciting.

Ten years ago, nobody knew about bus bulbs or slowing areas, or (pedestrian) plazas. And now, New Yorkers have a totally different vocabulary for their streets, totally different expectations.

They expect their streets to be safer, they expect there to be places where you can just sit and take it all in. They expect that they should be able to get on a bus and move fast. And so everything has changed. And I’m always excited when I see people on Citi Bike, I think that’s always a bit of a thrill.

Carlos Waters

Why did New York City’s Department of Transportation focus on protected bike lanes in your tenure?

Janette Sadik-Khan

Well, when I was appointed commissioner, I went to Copenhagen to see the bike lanes there. And one of the bike lanes that really caught my fancy was this parking-protected lane. They used the parked cars to protect the cyclists. And I thought it was a totally cool idea, and it wouldn’t cost a lot of money. All it was, was allocating space on the road.

And I was with my chief traffic engineer. I asked him if he thought this was work. He squatted down on his knees and took out the tape measure he brought with him. He got down and measured it and looked up and said, yeah, we can do this. And that was a really important moment in transportation in New York City.

But it wasn’t really about the engineering of the space and the allocation of the space, because you can move that space and preserve the parking and make a bike lane. But the real battle was going to be about the culture — about changing the hearts and minds of New Yorkers, of changing their minds about who their streets were for.

Right after I got back from Copenhagen, we put in the first parking protected bike lane in the United States. This was in 2007 in the fall. And we did it on Ninth Avenue, between 16th street and 23rd Street.

It was much better for pedestrians, it was easier to cross the street, because the crossing distance was shorter. Cars had dedicated turn lanes, so the traffic processed much better. And bikes had a dedicated lane.

And not surprisingly, we saw crashes go down. We saw much better for businesses — their retail sales went up almost 49 percent.

So it was a win for business, it was a win for drivers, it was a win for people on foot. And it was a win for people on two wheels. And that really set the stage for all that followed.

Carlos Waters

Are protected lanes politically harder to implement than conventional lanes?

Janette Sadik-Khan

You know, one of the benefits of parking protected lanes is that you can preserve the parking. There’s always a battle when you try to take away parking space. People get really passionate about it. Taking away a parking space is like taking away someone’s firstborn.

Taking away parking spaces is not for the faint of heart. And there is no super secret magic recipe that’s going to make it easier to do. But you need to make a case about what you are trying to do.

Our streets for too long have just been looked at as a place to move cars as fast as possible, from point A to point B, or to just serve as parking lots. And these cars basically sit on the side of the road unused 98 percent of the time. That’s not a really good use of one of the most precious resources a city has: its streets.

And so designing streets for people, that make it easier to bike, easier to walk, and easier to take the bus — that’s the kind of recipe for the future success of cities. And the cities that make these investments and changes are the cities that are growing and thriving in this century.

Carlos Waters

How do bike lane networks fit into this?

Janette Sadik-Khan

A bike network is a system that actually allows you to get where you needed to go. When I first started, so many of our bike lanes were a mile or two, and then kind of unceremoniously dump you into moving traffic.

You need a system that people can rely on to get them where they need to go, and it needs to be safe. And the way that we look at the health of bike lanes, and our bike lane network, is how many women and children are using the lanes. And so our goal was to create a safe and connected bike network.

And now there are almost 125 miles of protected bike lanes in New York City. It can be done, and now biking is not alternative transportation. It’s basic transportation.

Carlos Waters

Should communities still make conventional lanes then?

Janette Sadik-Khan

You know, the thing is that every society is different, and every street is different. We did what we could to create as much protected space as we could for cyclists. But I’m not a fan of sharrows [shared-lane markings]. I don’t think they provide the kind of protection you need to get the number of cyclists out there that you want to see on the streets of your city.

Carlos Waters

One of my favorite things about your success with bike lanes in New York is how fiscally responsible it is.

Janette Sadik-Khan

When you look at the cost of the bike lanes that we put in, it was less than 1 percent of our capital budget. And 80 percent of the funding from our bike lanes came from our federal government.

So, you know, the bike lanes were like 99 percent of our headlines, but they were only 1 percent of the budget. I don’t think there’s a better investment. If you want to build a better city, you can start by building better bike lanes.

Sourse: vox.com