You can tell a lot about what fans think of the subjects of their admiration by how they portray them. In the age of the celebrity politician, that’s true for fans of presidents and presidential candidates, too.

Barack Obama, for instance, inspired a huge amount of fan art (most famously the Shepard Fairey “Hope” poster), much of which positioned him as the fulfillment of years of struggle, and, at times, as a kind of American superhero, chosen by destiny to triumph in the struggles of our time. And when it looked like Hillary Clinton might become the first female US president, fan art sprang up painting her as a feminist hero and a badass.

But the Obama fan art canon is rivaled, and possibly dwarfed, by the work that’s been created about Donald Trump — and that work is just as revealing about the way Trump’s fans think about him.

Two of the most interesting varieties of Trump fan art exemplify two ways that his fans think about him: in traditional, pastoral terms, and in apocalyptic, warlike ones.

What ties both visions of Trump together, though, is how they embody versions of his most popular slogan, “Make America Great Again,” illustrating the slogan’s power as a piece of marketing. It’s punchy, but also vague and capacious, with enough room for anyone to imbue it with meaning. And these two ways of illustrating it — literally — help show just how flexible it is.

Jon McNaughton paints pastoral, imagined images of the president as a keeper of tradition

The single most famous pro-Trump artist, Jon McNaughton, mixes fantasy with historical and biblical signifiers in his work, figurative paintings that in some ways resemble works from the 18th and 19th centuries.

McNaughton probably first crossed the radar of average Americans days after the 2016 election, when Sean Hannity bought his 2010 painting The Forgotten Man:

McNaughton prefers to explain his paintings in detail on his website, with annotations describing each figure and symbol and, at least in the case of The Forgotten Man, a long list of responses to critics of the painting.

But though The Forgotten Man was picked up as a symbol of “what [Trump’s] election was all about” by Hannity, McNaughton writes on his website that it was painted “in response to the passing of the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare).” So it’s not specifically about Trump.

In fact, for much of his career, McNaughton, who is Mormon, wasn’t a political painter. He stuck mostly to general landscape and religious paintings.

But that changed in the Obama era, when McNaughton took to his canvas in order to depict Obama as a Constitution-burning, democracy-hating demagogue who spent his time alternately fiddling and golfing while the country itself goes up in flames. He has depicted Andrew Breitbart as a courageous activist in a war zone, Hillary Clinton as a con artist, and congressional Democrats as driving Jesus out of the Capitol.

Now, on McNaughton’s website, his politically oriented paintings are filed under a “Patriotic” heading, subdivided into three categories: Americana, Political, and “Conservative Drawings.” (That last one contains only two slightly baffling items, a drawing of Kim Jung Un and one of John F. Kennedy, both accompanied by quotations.)

Most of McNaughton’s Obama-oriented work is in the Political category, while most of the Trump-oriented work is filed under Americana, along with depictions of Ronald Reagan, George Washington, Billy Graham, cowboys and native Americans, military men and women, and several of Jesus standing amid soldiers and figures from American history.

But it’s the Trump depictions that really stand out, mostly because of the fantasies of greatness they represent. McNaughton’s Trump images don’t show the president in situations drawn from the headlines; instead, they imagine him as a hybrid of everyman and American hero, a defender of liberty and an instructor in the American virtues of pulling oneself up by one’s own bootstraps. The Trump of McNaughton’s imagination is a defender of the trappings of the great American experiment.

For instance, the painting Respect the Flag depicts, in McNaughton’s own words, “President Trump picking up a shredded and trampled flag off the football field. He holds a wet cloth in his right hand, as he attempts to clean it.”

“The way Trump called out the NFL for not supporting the standing of the national anthem was an example of how a President should lead, with courage to say and do the right thing regardless of the reaction of others,” McNaughton writes in his artist’s statement.

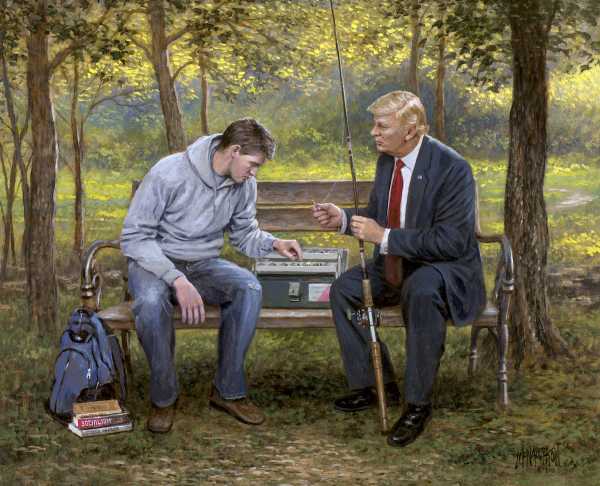

Another painting that draws on an imagined occurrence is Teach a Man to Fish, in which Trump holds out a fishing rod fitted with a lure to a young white man wearing a gray hooded sweatshirt:

“I imagined President Trump sitting next to a young college student,” McNaughton wrote in his statement. “His pack is beside him and his Socialism and Justice Warrior books laid aside. He listens to Trump’s proposal and looks at the different bait he can use to catch his fish. Trump offers him a fishing pole. Each of us has the freedom to choose our own destiny.”

McNaughton has also weighed in on special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into Russian interference in the 2016 election. In Expose the Truth, he depicts Trump collaring a shaken Mueller and peering at him closely through a magnifying glass as members of Congress look on:

The label beneath the painting on McNaughton’s website explains that it’s about Robert Mueller and his council of “at least 17 partisan Democrat attorneys” who “ignore the mounting verifiable evidence against Russian collusion with the DNC and the Clinton Foundation.”

“There comes a time when you have to take a stand to Expose the Truth!” McNaughton writes.

Other paintings of Trump include Make America Safe, which shows him standing in front of a white picket fence holding a key; You Are Not Forgotten, in which he stands by as a white man and woman water a tiny seedling; and a more classically rendered portrait, underneath which he writes, “I am hopeful that President Trump will be able to help make America great again. He’s got the look he gets when the Fake News is trying to lie again. Go get them Trump!”

Some have pointed out the similarities between McNaughton’s images of Trump and the state art of North Korea that venerates the Kim family; the New Yorker’s art critic Peter Schjeldahl noted some continuity between The Forgotten Man and a 1934 Maynard Dixon painting titled Forgotten Man, prints of which are sold by Brigham Young University, where McNaughton studied for a time.

Obviously, McNaughton feels much more warmly toward Trump than toward Obama, and seems to be convinced of the version of current events peddled by Fox News and White House officials.

But it’s interesting to see how that manifests in his art about the two presidents. While paintings about both are based on imagined scenarios, Obama’s are often accompanied by images of burning landscapes and dark clouds, his face usually twisted into an angry or evilly delighted expression. Trump’s, by contrast, show the president as resolute and square-jawed; even in a relaxed image like You Are Not Forgotten or Teach a Man to Fish, his smile is slight and dignified.

To date, however, McNaughton has not depicted Trump in situations in which he’s actually rescuing a burning America. In fact, all his Trump imagery is more devoted to tying Trump to traditional symbols of America: the flag, agricultural cultivation, the brave soldier, the white picket fence. “Making America great again,” in McNaughton’s formulation, is preserving the images he and others most closely identify with America.

In interviews with the artist, McNaughton’s loyalties seem more tied to an idyllic throwback version of a (mostly white, suburban, and Western populist) American golden age than the figure of Trump himself, about whom he has expressed reservations at times while maintaining a baseline of support. He believes Trump could take his place in history as a truly great president, but that will depend on how he defends those American symbols.

That idealist optimism lies in stark contrast to other images that arise among another faction of Trump-supporting art.

Dinesh D’Souza’s Death of a Nation poster draws inspiration from apocalyptic imagery and “hidden” history

You can most clearly see the contrast between McNaughton’s version of Trump and others by comparing it to some of the more bombastic imagery of the president. Much of that flourishes in the stranger corners of the internet — subreddits and 4chan and the like — where Trump’s head is photoshopped into memes, or he’s integrated into scenes from apocalyptic video games.

A lot of these images can’t be taken too seriously, in the sense that their creators often work from a nihilistic sense of trolling irony to confuse interlocutors and spread alt-right ideas. So when someone, for instance, depicts Trump walking on water to rescue a sinking Statue of Liberty or photoshops Trump’s head onto Napoleon’s body, it’s done half in jest, half in an attempt to confuse critics.

But memes are designed to spread into the mainstream and in some cases be taken seriously; that’s sort of the joke. And while the president and his associates have retweeted alt-right memes in the past, some of the imagery that’s sprung up on 4chan and the like seems to have made its way into more earnest depictions of the president.

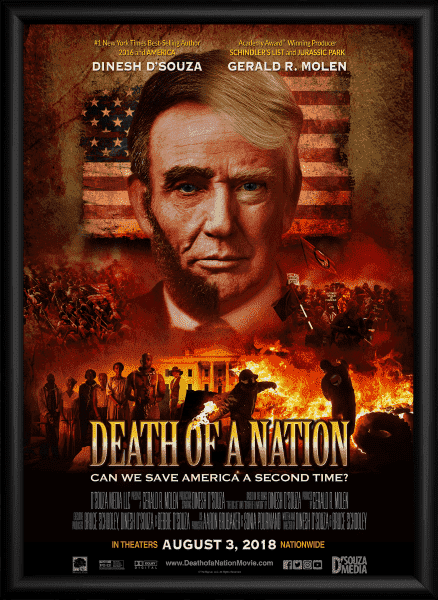

Perhaps the most mainstream and unforgettable of these is the poster for the newest film from conservative filmmaker/self-styled incendiary Dinesh D’Souza, Death of a Nation, which seems to draw on some of the tropes favored by the fan artworks birthed in the recesses of 4chan.

The poster is mostly filled with a sternly resolute man’s face. The left side of the face is Abraham Lincoln’s; the right is Donald Trump’s. Lincoln’s iconic dark hair and beard fade into Trump’s blond hair, swooping across his forehead. Both half-faces have lined foreheads and faintly pursed lips. It’s a look of wisdom and determination.

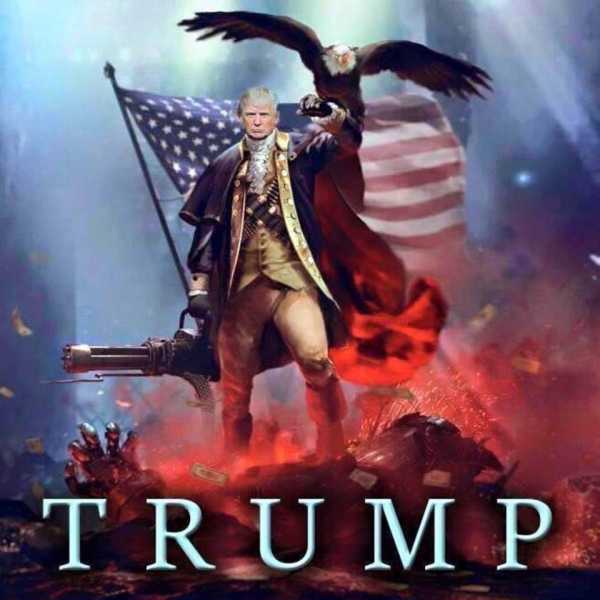

The conflation of Trump and another heroic historical figure is one of the most common tropes in Trump fan art — there’s the aforementioned Napoleon image, for instance (though one assumes the creators aren’t advocating that Trump meets the same end as Napoleon). Or consider one of the more famous triumphalist Trump images:

Here, the president, clad in Revolutionary-era garb with a bald eagle perched on his left arm, holds a machine gun fitted with a bayonet. He stands on the smoldering remains of what appears to be some kind of robot, all in front of a waving American flag.

The image appears to be a photoshopped version of artwork featuring George Washington produced by the Call of Duty Endowment, a fund set up by the Call of Duty video game franchise to aid veterans in getting jobs after they leave the military:

It’s not clear who first photoshopped Trump’s head onto Washington’s, but it seems likely to have emerged from one of the troll-populated corners of the internet that makes similar works, such as 4chan or the /r/The_Donald subreddit. But regardless of its origin, it’s clearly a completely imagined image. (Although the real Trump has actually had a bald eagle on his arm, he dodged when it tried to peck at him.) That imagined aspect aligns it with both McNaughton’s work and the Death of a Nation poster.

But there’s another kind of continuity between this image and D’Souza’s, both of which glow with something that seems like a cross between the fires of war and the fires of apocalypse.

The marketing materials for Death of a Nation say it “cuts through progressive big lies to expose hidden history and explosive truths” through “stunning historical recreations and a searching examination of fascism and white supremacy,” which plays out in the poster’s imagery: On Lincoln’s side are Civil War soldiers on the battlefield and shackled black slaves; on Trump’s, antifa symbol-bearing protesters with posters that say things like “Another World Is Possible” and “Immolate Your Local Fascist” and throwing objects into burning flames.

Like D’Souza’s three previous films, Death of a Nation is in essence a partisan argument seeking to recast current events and American history into a meta-narrative that posits an America in need of rescuing. The first, the 2012 film 2016: Obama’s America, positioned then-President Obama and his supporters as the threat. The 2014 film America: Imagine the World Without Her saw figures like Saul Alinsky and Howard Zinn, along with restraints on capitalism, as the main threat. And the threat posited in the 2016 film Hillary’s America: The Secret History of the Democratic Party is right there in the title.

For Death of a Nation, D’Souza revisits the claim that liberal historians have long covered up the secretly pro-slavery, pro-fascist, pro-white supremacist history of the Democratic Party. The effectiveness of that argument relies on the notion that D’Souza’s audience is unfamiliar with the common historical account of Southern Democrats switching parties as well as the Southern strategy. (Vox has videos on the histories of both the Republican Party and the Democratic Party if you need to brush up on your high school history.)

But that argument nonetheless has been effective, at least among his target audience. D’Souza’s books and films on the subject have been huge hits among conservatives: 2016: Obama’s America is one of the highest-grossing documentaries of all time, keeping pace with Michael Moore’s Fahrenheit 9/11, and D’Souza’s books often reach the New York Times nonfiction best-seller lists.

So while the tattered American flag on the Death of a Nation poster recalls McNaughton’s Respect the Flag, it also recalls a flag that has been on the battlefield — in this case, the field of the culture war. And the imagery of fire that forms the base of the poster is also common in Trump fan art, a handy symbol of chaos and destruction.

It’s hard to control the meaning of images — and of campaign slogans. But that’s a feature, not a bug.

Death of a Nation is being pitched, at least through its imagery, at a certain segment of Trump fans — those who populate the subreddits and 4chans where the alt-right lurk, or people like former adviser Steve Bannon — who are interested less in preserving the kinds of American traditions that appear in McNaughton’s paintings than in tearing the whole thing apart.

The president has at times tried to disavow this point of view explicitly — he criticized Bannon in January and called for his supporters to “take our country back and build it up, rather than simply seeking to burn it all down” — but images tying his face to flames continue to persist.

And it’s hard to control an image like that. For the president and some of his supporters, the implication may be that Trump will save a country on fire, just as McNaughton positioned Obama among flames to suggest he was ignoring a country on fire. In this formulation, Trump will put out the raging fire.

But for other supporters, the flames are part of the attraction: Trump’s MAGA agenda is, to them, about razing the “establishment” to the ground and putting him and his supporters in places of power. He’ll light the fire. The “greatness” of Trump has to do with his ability to trample his detractors and root out enemies.

That’s what’s so tricky about art. It’s open to interpretation. And while McNaughton works hard to make sure that the people who see his art are left with a crystal-clear sense of what his intentions were, the 4chan crowd courts vagueness and distortion. That spills over into more earnest versions of the same, like D’Souza’s movie poster, intended to bring you into the theater to find out whether Trump will be burning down the establishment or putting out that same fire. There’s a method to the imagery, and its many possible meanings only increase its effectiveness.

That sets up the two overlapping but differing definitions of “greatness” for fans of the “Make America Great Again” agenda. One has to do with preserving a certain version of a golden age most closely associated with times of American expansion and postwar affluence; the other has to do with trampling one’s enemies, abroad but especially at home, with a show of might and power.

So the art of Trump’s most ardent fans ranges from idyllic to imagined. What doesn’t change, however, is that it — like fan art of nearly all types — is interested in constructing and preserving a myth around the subject of its admiration. The proliferation of images on the internet and the ease of reproduction only makes it easier for these to spread, morph, and become something new.

MAGA will likely remain the rallying cry for Trump fans for a long time yet, and its power as a slogan for a certain partisan segment of the American public promises to stick around long past the eventual end of Trump’s presidency. But that’s less because of Trump himself and more because it leaves room for those who latch onto it to project onto its four words their own vision of American exceptionalism — whether that vision is populated by triumphant war heroes trampling foes on the battlefield, or by saplings, gently mended flags, and picket fences keeping interlopers out.

Sourse: vox.com